Given Bangladesh’s strategic location and importance as a trade partner, its internal security and stability are essential to US national interests in South Asia. Once celebrated for its religious tolerance, Bangladesh has now become a battleground of ideas between an increasingly vocal and powerful collection of Islamist groups and the vast majority of Bangladeshi citizens who still cherish the ideals of secularism, pluralism, and democracy. While numerically smaller, the Islamists, who espouse a narrow sectarian agenda and seek to create a theocratic state with limited rights for minorities and women, are rapidly gaining ground.

Accordingly, the plight of religious minorities and atheists has become increasingly precarious as there has been a marked increase in religiously motivated violence coinciding with the rise of domestic and international Islamist groups.

While Islamists have been responsible for the majority of the violence, the ruling Awami League (AL) has also contributed to deteriorating human rights conditions in the country by suppressing dissent and basic civil rights, pursuing policies that appease and empower Islamists, maintaining and enforcing a legal framework that discriminates against minorities, and directly participating in or failing to stop acts of violence against minorities.

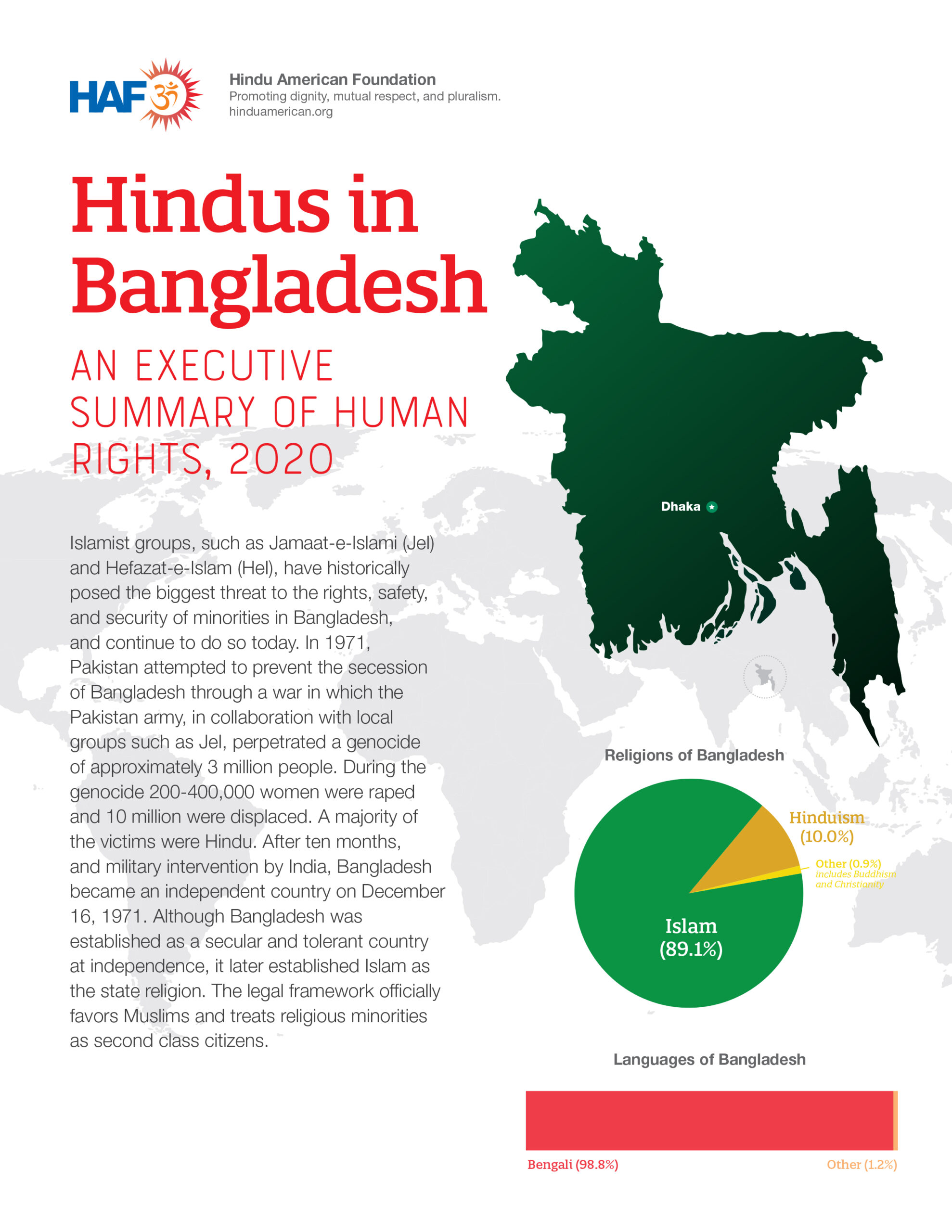

Hindus, Christians, Buddhists, Shiite Muslims, and Ahmadiyya Muslims frequently “face harassment and violence, including mob violence against their houses of worship,” (Freedom House, 2020) with little or no consequences. Religious minorities are further socially marginalized and underrepresented in government positions, while the legal system continues to favor Muslims and Islam as the state religion.

Islamist groups in Bangladesh, most notably Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI), wield tremendous power through extensive grassroots networks and exert disproportionate influence over the country’s political, social, legal, and religious affairs. JeI, along with its student wing, Islami Chhatra Shibir (ICS), strive to create an Islamic state in Bangladesh, as explicitly laid out in its charter. JeI and ICS, in conjunction with the West Pakistani military, were responsible for committing genocide against the country’s Hindu population in the 1971 War of Independence. Since then, they have consistently utilized violent tactics to achieve their religio-political goals, including bombings, political assassinations and targeted killings, attacks on security personnel, and mass violence against minorities and atheists. (SATP, 2017)

And with the rise of social media over the past decade, outspoken bloggers critical of growing extremism came into the limelight and drew the ire of Islamist groups, such as JeI and Hefazat-e-Islam, who accuse them of blasphemy and threaten to kill them. Countless bloggers have gone into hiding, fearing for their lives and curtailing their rights to freely express their views against religious extremism.

As a result of the widespread violence and growing intolerance in the country, many Hindus and Buddhists have fled and sought refuge in India. Although many Bangladeshi Hindu refugees have been living in India without formal legal status, the Indian government took some positive steps by passing the Citizenship Amendment Act in 2019 to expedite citizenship for religiously persecuted refugees from Bangladesh (along with Pakistan and Afghanistan) living in India prior to 2015. The provisions of the CAA, however, have not yet been implemented.

At the same time, the Bangladeshi government has refused to repatriate approximately 550 Hindu Rohingya refugees back to Myanmar that are living in refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar district. Bangladeshi officials showed disregard for their plight, despite the refugees’ desire to return to Myanmar and the Myanmar government willing to take them back. The Hindu refugees originally came to Bangladesh in 2017 after Muslim Rohingya militants with the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army attacked two Hindu villages in Rakhine state, killing nearly 100 men, women, and children and abducting several residents. (BenarNews, 2021)