Origins of “Hindutva”

Hindutva as a single word literally means ‘Hindu-ness’. Set against the thousands of years of dharmic traditions, it is a very modern term. In 1888, one of the earliest references to Hindutva, Bengali author Bankim Chandra Chatterjee characterized its essence as Divine love, stating, “The divine is present in all human beings, so that if I love the divine reality, I love all humanity as well, and if I do not love all humanity, I cannot love the divine reality. As long as I have not understood that I and the world are not different, I have not gained either knowledge, dharma, devotion, or love. This universal love lies at the root of Hindu dharma, and there can be no Hindutva without this inalienable and indivisible love.”

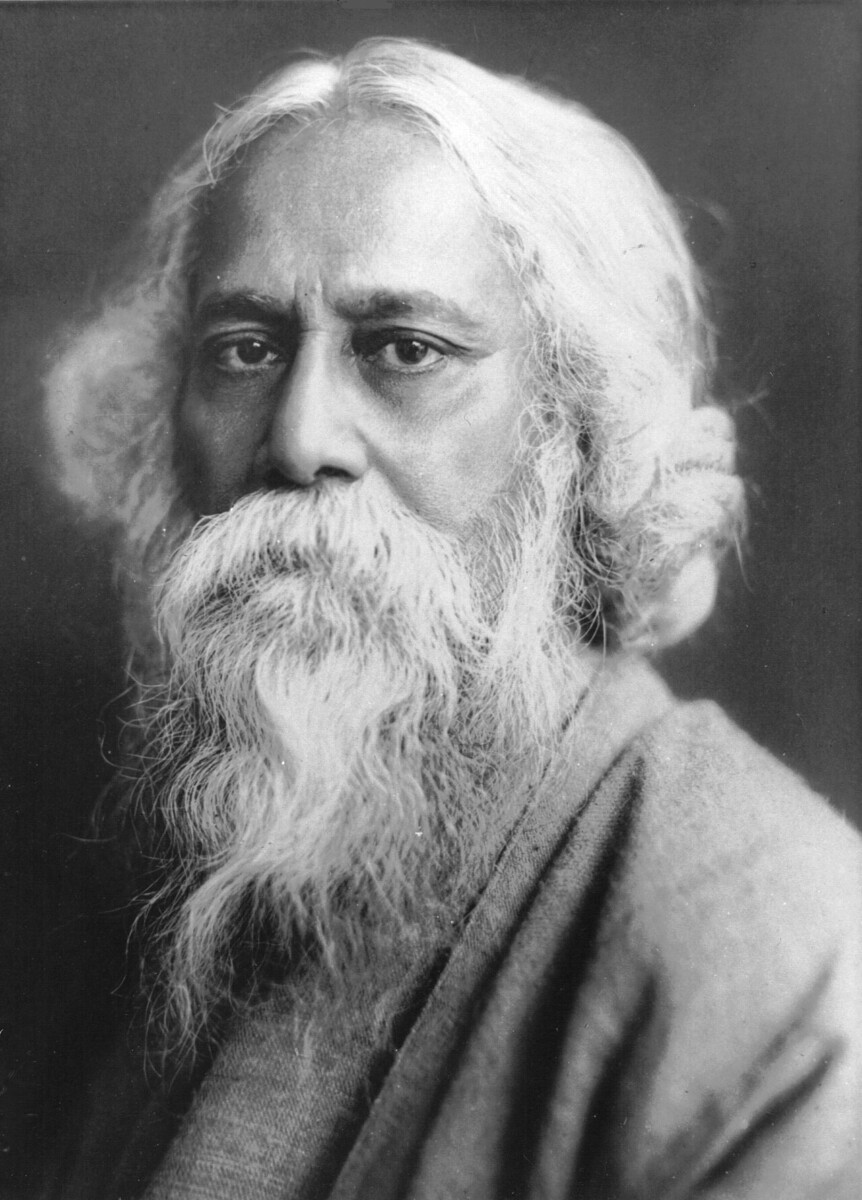

In 1901, Nobel-prize winning author Rabindranath Tagore wrote about how Hindu culture has for centuries encompassed a vast array of regional customs, beliefs, and peoples, some entirely contrary to one another, yet still with an underlying unity to them. Tagore’s beliefs predated Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s shaping of a political philosophy of Hindutva, yet it resonates with Savarkar’s definition of Hindutva and the key markers of Hindu culture.

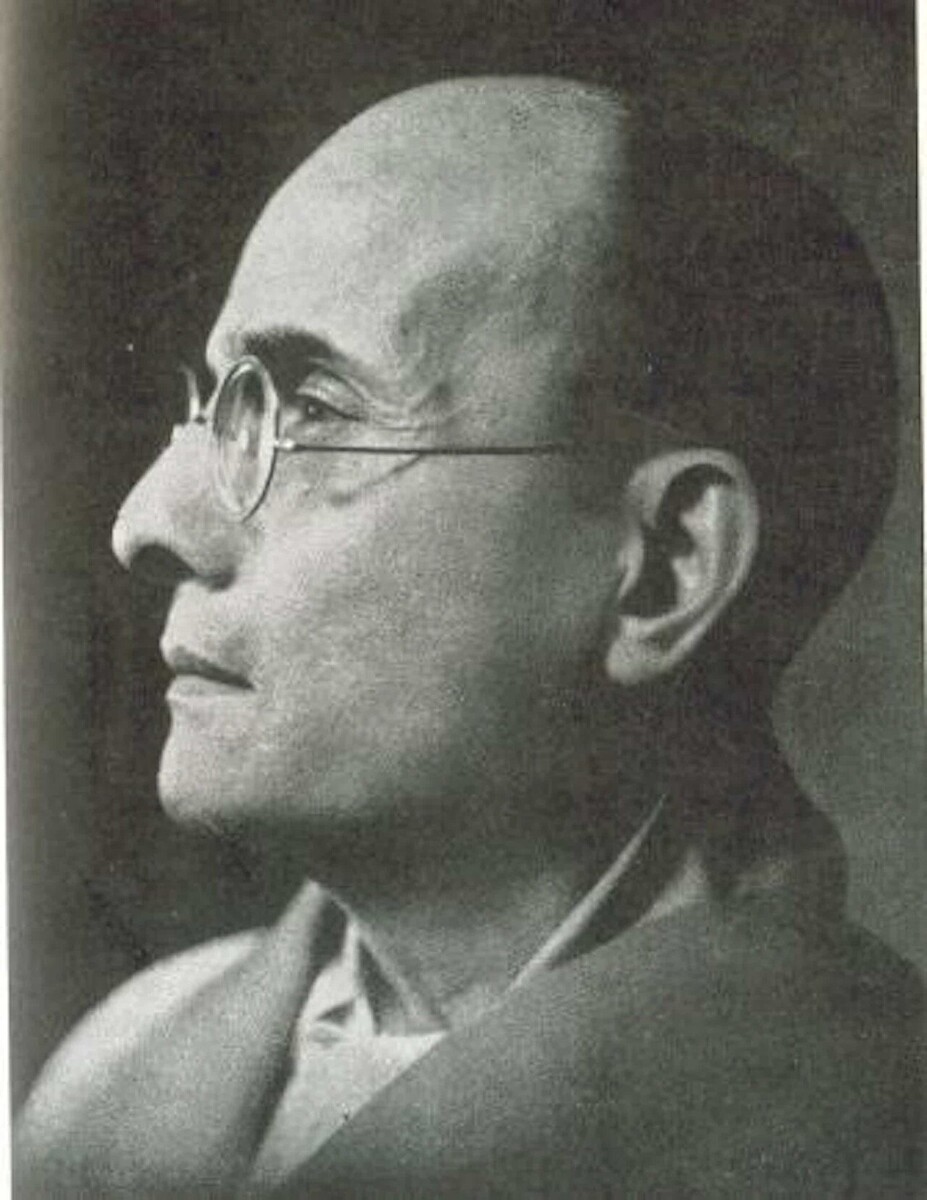

In 1939, building on ideas first articulated in 1923, Savarkar defined a Hindu as “someone who regards and owns this Bharat Bhumi, this land from the Indus to the Seas, as his Fatherland as well as his Holyland; i.e., the land of the origin of his religion, the cradle of his Faith.” After listing out various spiritual lineages that today would be identified as Hindu, plus Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, as being part of “Hindudom”, Savarkar notes, “Consequently, the so-called aboriginal or hill tribes are also Hindus: because India is their Fatherland as well as their Holyland of whatever form of religion or worship they follow. This definition, therefore, should be recognized by the Government and made the test of Hindutva in enumerating the population of Hindus in the Government census to come.”

Such a distinction between those spiritual traditions originating in India and those that did not, nor identify India as a “‘holyland”, does certainly exclude Muslims, Christians, Zoroastrians, and Jews as being Hindu. (Such a distinction these communities certainly do not contest; although most of today’s Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs generally consider themselves outside the umbrella of the word ‘Hindu’.) The line between spiritual traditions historically originating in India and those originating elsewhere was endorsed by no less than Dalit advocate Dr. BR Ambedkar and ultimately enshrined in the Indian Constitution under his direction. This distinction is often cited by Hindutva’s critics as evidence that the philosophy posits that non-Hindus aren’t really Indian or shouldn’t be equal members of India as a nation. This is simply not the case, based on the historical record.

Savarkar’s words from 1909, recorded at an event in England at which Mahatma Gandhi was present and is said to have agreed with, support this: “Hindus are the heart of Hindustan … [but] just as the beauty of the rainbow is enhanced by its varied hues, Hindustan will appear more beautiful if it assimilated all that is best in Muslim, Parsi, Jewish and other communities.”

Further to this point, in 1937 Savarkar stated, “Let the Indian state… not recognize invidious distinctions whatsoever as regards the franchise, public services, offices, taxation on the grounds of religion or race. Let no cognizance be taken whatsoever of a man being Hindu or Mohammedan, Christian, or Jew. Let all citizens of that Indian State be treated according to their individual worth, irrespective of their religious or racial percentage in the general population.”

Much more recently, in 2016, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, speaking at a global Sufi Muslim conference in New Delhi, drew positive parallels between Sufism in India and the Bhakti tradition, as well as with Sikh practices, before concluding, “Sufism’s contribution to poetry in India is huge. Its impact on the development of Indian music is profound. It is this spirit of Sufism, the love for their country and the pride in their nation that define the Muslims in India. They reflect the timeless culture of peace, diversity, and equality of faith in our land.”

As for other modern expressions of Hindutva as well as how Hindutva views non-Hindus, the following long statement from 2024 by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh—the leading organizational supporter of Hindutva—is telling and parallels millennia-old definitions of the word ‘Hindu’: “The RSS…believed from day one that this country belonged to the Hindus. The RSS perceives Hindu as a term that defines the national identity of the people living in this country. It is not a religious or sectarian identity. It is as the Supreme Court of India observed, a way of life. Hindus have their own ‘View of Life’ and a ‘Way of Life’. Within the Hindu fold there are innumerable sects and subsects that have perfect freedom to follow their ways of worship. But the national identity of the people of this country is essentially Hindu. The RSS also believes, respects, and follows the principle of Unity in Diversity as a quintessence of the Hindu worldview. For example, an average Hindu believes that the Truth is one and can be expressed, told, described, and attained and realizes in different ways all leading to the One Supreme Reality. Anyone who subscribes to this worldview, accept and respect Bharat’s history [India’s history], nurture the country through their social values and make sacrifices to protect this value systems are Hindus in the eyes of the RSS, notwithstanding their religious moorings and affiliations.”

As for the place of Christians and Muslims in Indian society, the RSS states: “Christians and Muslims [in India] have not come from some alien lands. They are all children of Mother Bharat. At some point of time in history their ancestors might have changed their religion and ways of worship. But that does not separate them from the Hindu society in the larger context.” Certainly, one can find examples of supporters of Hindutva, members of the RSS or BJP, or other aligned organizations not embodying the lofty language cited above. As is the case with all secular philosophies or spiritual belief systems, one should expect gaps between theory and practice. However, to downplay that the leading proponents of Hindutva over the past century and a half presented their political philosophy as a broadly inclusive one rooted in reverence for the culture of India, which they label ‘Hindu’ as has been done for more than a millennia, rather than an exclusionary one based around contemporary narrower religious categories played against one another, as critics of Hindutva regularly do and continually allege, ignores entirely the words of the leading minds and organizations espousing Hindutva.