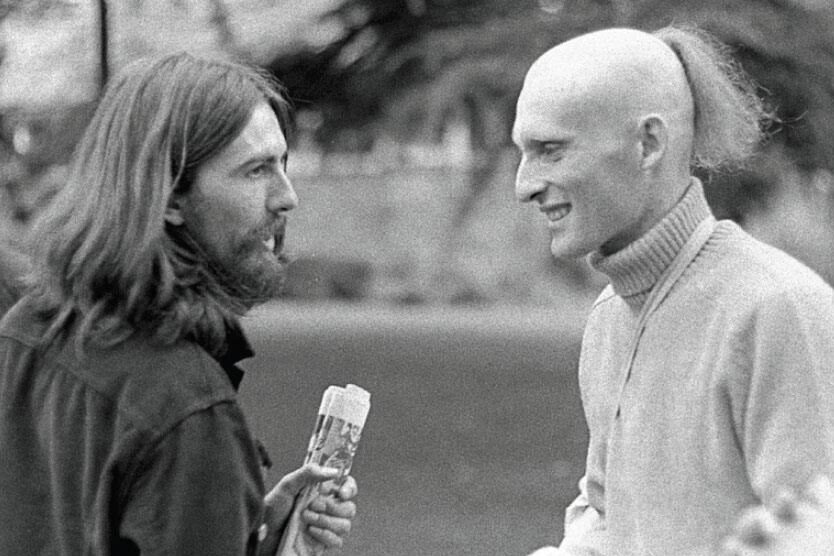

Photo by Gurudas

I look forward to Thanksgiving every year for the same reasons anyone usually does: the long weekend, good food, and above all, time with friends and family. This year, however, I looked forward to the holiday for a completely different reason, one that, I must admit, overshadowed any of my previous standard reasons, even the “friends and family” part (only joking of course…well, mostly).

This year, Peter Jackson’s Get Back docuseries with over seven hours of unseen footage of the Beatles creating what would become their iconic Let it Be album was to be released over the holiday weekend, and like any true and good fan, I was eager to binge every hour.

So when Thanksgiving finally arrived, like a kid on Christmas morning, I turned on Disney+, found part one of the three-part series, and pressed play. Patiently sitting through the intro, I assumed a sober expression — like that of a student who was about to dive into a serious study of an important and newly unearthed part of history — so I could properly assimilate what I was about to watch.

Yet when the opening scenes began to unfold, I couldn’t help but break into a smile, as the camera zoomed in on a cross-legged man hunched in the corner of Twickenham Studios with a shaved head, red beads around the neck, and hand in a bag.

To most viewers, the presence of this person would probably appear incredibly random. After all, he clearly is not part of the cast, crew, or family related to the Let it Be project in any way. And though the docuseries makes it known by caption that he is Shyamsunder Das (Friend of George Harrison) — after John Lennon asked his bandmates “who’s that little old man, one of the Hare Krishna’s or something?” — no real explanation is given as to what that man is actually doing there.

But I knew.

Besides being an enormous Beatles fan, I also grew up as part of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), a religious movement that teaches the Hindu tradition of bhakti yoga (the yoga of devotion). I thus knew that this man wasn’t just any “Hare Krishna,” he was a very important pioneer of the movement.

Shyamasundar (not Shyamsunder as spelled in the docuseries) was one of six people (three married couples) who went to England in 1968 with the hopes of establishing an ISKCON center in London, as desired and encouraged by their guru and the movement’s founder A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.

Other than North America, where the burgeoning movement had barely begun to take shape, bhakti yoga was a foreign concept to the rest of the Western world. Shyamasundar, therefore, had a grand idea to expose the tradition to as many people as possible in the most appealing way: by meeting the Beatles. If the most popular and influential band in the world became interested in bhakti yoga, then surely the rest of the world would as well.

Though such a plan could be described as delusionally ambitious, Shyamasundar was determined to try. Thus after convincing his wife Malati, they and two other couples — with barely enough money to pay for the flights — flew to England towards the beginning of September of 1968, uncertain of what to expect.

Photo by Gurudas

Knowing that the best way to relate to the Beatles would be through music, the cohort immediately formed a kirtan band upon arrival. When they weren’t looking for an appropriate and affordable building to turn into a temple, attempting to make connections with anyone who might be able to help their cause, or simply scraping enough money to get by, they were rehearsing for hours every day.

Calling themselves “The Radha Krishna Temple,” the group eventually started performing gigs throughout the city. Hearing that the Beatles’ were searching for new talent to record under their newly founded label Apple Records, the Radha Krishna group recorded and submitted a demo tape. A couple of weeks later, however, they received a boilerplate rejection letter from Peter Asher, the label’s A&R manager.

But they weren’t discouraged. For them, sending the demo was merely a first step. Even when faced with a seemingly dead end, they believed in their cause, and sincerely wanted to please their guru, who went to extraordinary lengths to please his own guru by bringing bhakti yoga (as practiced in the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition) to America, where it was now catching on like wildfire.

The group thus persevered, certain that if they pushed forward and also went to extraordinary lengths, then they too would see extraordinary results, even if it took a little bit of time.

And such results indeed took only a little bit of time to manifest.

As described in his book Chasing Rhinos With The Swami, Shyamasundar received a call on December 10 from his once college roommate Rock Scully, a prominent figure out of Haight Ashbury who was now a manager of the Grateful Dead. He and seven others, including a number of Hell’s Angels, had just flown into Heathrow and needed a place to crash for the night.

Giving them a place to stay (a warehouse in which the cohort had been living), Shyamasundar eventually learned that the group had plans to attend a pre-Christmas party at Apple, where the Beatles were expected to be in attendance. Seeing his opportunity, he asked Scully if he could tag along, to which his old college roommate quickly assented.

So three days after picking Scully and his friends up from the airport, Shyamasundar, with a shaved head, tilak on his forehead, and a dhoti (traditional Indian garment) tied around his waist, made his way over to Apple Corps.

The party was in a big lounge, crowded with roughly 50 people — including rock stars, hippies, and guys in suits — mingling as they waited for the Beatles to emerge from a couple of doors behind which they were said to be having a meeting.

Finding his way to the far end of the room opposite the doors, Shyamasundar took a seat.

After several hours, the doors finally opened to Paul, John, and Ringo, who quickly stuck their heads out one by one, before heading straight for the exit without talking to anyone. Minutes later, George also poked out his head, scanning the room before him. Instead of following in his bandmates footsteps, however, he walked directly to the back of the room to a stunned Shyamasundar, gave him a grin and said, “Hare Krishna! Where have you been? I’ve been waiting to meet you!”

Immediately the two connected, as George inquired about one Hindu concept after the next. Having already been to Rishikesh, where he spent time with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the Beatle was not unfamiliar with such concepts. His questions were thus straight to the point. He had gotten a hold of a record of Shyamasundar’s guru chanting Hare Krishna, and wanted to learn more about him. As their conversation came to an end, George asked Shyamasundar if he would come over to his place a few days later, where they could talk at greater length.

Over the next several weeks, the two became fast friends. After Shyamasundar visited George at his house, George decided the rest of his bandmates should learn about ISKCON and its founder as well. As such, he asked Shyamasundar if he would come to Twickenham, and explain bhakti yoga to John, Paul, and Ringo.

Hence on a cold January morning, Shyamasundar found himself sitting in the corner of Twickenham Studios, softly chanting the Hare Krishna mantra to himself, anticipating the moment George would call him over to meet the rest of the band.

For those of us in ISKCON and other various circles within Hinduism, the rest is history. Shyamasundar met the band when George signaled him over. He answered all of their questions and impressed John, who later offered him and his friends a place to stay on his property in Tittenhurst until they could open a temple, which George eventually helped them secure at Bury Place in London.

George went on to help the Radha Krishna Temple produce a single titled Hare Krishna Mantra, which sold 70,000 copies on the first day of its release, and subsequently peaked at the number 12 spot of UK’s national singles chart. Following its commercial success around the world, he then helped them produce a full album, sparking widespread interest in ISKCON.

Soon the Bury Place temple became much too small for the rapidly growing movement. This led to George donating Bhaktivedanta Manor, a large temple set in the Hertfordshire countryside of England.

A thriving community blossomed around this temple, which still exists today, with millions of people visiting it every year, including myself, as it is the very community my wife grew up in.

And so while most watching the Get Back docuseries will probably see the hunched man in the corner of Twickenham as nothing more than some random presence, I know better. I know he was there for an extraordinary purpose: to help cement a friendship that would create a powerful spiritual community — one that has enriched and affected the lives of millions, including my own.

To learn more about the history of ISKCON, George Harrison, and his relationship with the Hare Krishnas, you can order all three volumes of Shyamasundar’s “Chasing Rhinos with The Swami” at chasingrhinos.com.