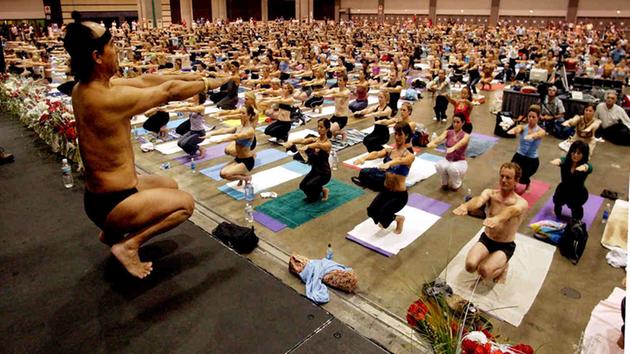

Again, allegations of sexual abuse by one of the most influential and revered yoga gurus, Ashtanga founder K Pattahbi Jois, have made mainstream headlines. This time in The New York Times. That article comes right at the same time that Netflix has released a jaw-dropping documentary on the many incidents of sexual assault by Bikram yoga founder Bikram Choudhury .

These first-hand accounts are not revelations in that these stories have been circulating in the yoga community for some time, but they are nevertheless shocking.

Though Bikram’s actions were far more widespread and severe, including allegations of outright rape, both cases shock because of the undoubted wrongness of the behavior and actions as yoga gurus, and they shock because they once again show how the yoga community is no more immune than any other community from the sort of power imbalances in gender relations so vividly and dramatically brought to light by the #MeToo movement.

All of this said, what these renewed accusations against K Pattabhi Jois and the charges against Choudhury drive home is that a guru can be very much fallible in ordinary social affairs.

As such, the reverence we rightly show for them, for the knowledge and wisdom they impart, must be balanced and grounded. We can accept the teachings of a guru — acknowledging that there may be teachings and methods of teaching that we don’t fully understand — but also must never lose our own moral compass.

A poignant example of this takes place in the Hindu epic, the Mahabharata. The five Pandava brothers spent their youth studying under their guru Dronacharya. As they grew to rule their kingdom, they continued to love and respect him as their guru. But when the lines were drawn for the epic war of dharma versus adharma, the five brothers sided against their guru. Seeing his guru and loved ones on the opposing side cause Arjun the great angst that led Krishna to deliver the Bhagavad Gita on the battlefield, reminding Arjun that his utmost duty is to uphold dharma.

Traditionally, the word guru refers to a master teacher who has great knowledge of or skill in a particular subject area, such as music, dance, sculpture, or other arts.

When used in reference to a religious or spiritual teacher, however, a guru is one who not only has deep knowledge that can lead to moksha (liberation or enlightenment), but also has direct experience of Divine vision and grace which they have assimilated into their way of being.

Thus, the literal translation of ‘guru’ is “dispeller of darkness.”

For ages, gurus tested students before accepting them. And students likewise were expected to make an assessment of a guru before beginning study. This assessment, from both sides, continues through the course of study.

A traditional maxim states that you can judge a guru by their students. This is why upholding teaching lineages — participating in what’s known as the guru-shishya relationship — remains important in an age when anyone can set up a YouTube channel of asana classes after a mere 200 hour of study and call themselves a yoga teacher.

Being part of a lineage of teachers and students provides a way for potential students to judge the worth of the teachings, the teacher’s methods, and ultimately the teacher. It also provides a dataset, if you will, to examine for both positive and potentially negative feedback — is the instruction effective, are students satisfied, is the teacher truly living up to their reputation and living what they teach.

Ultimately, in all our relationships, we must remember and emphasize the ethical foundations of yoga — the yamas and niyamas.

Ahimsa (non-harming), satya (truthfulness), brahmacharya (faithfulness and restraint), tapas (discipline), and svadhyaya (self-study) all seem particularly apropos for deeper consideration in the yoga community. If we practice or teach asana without any consideration of yamas and niyamas, then the practice is less yoga and more a form of exercise.

Ishvara pranidhana (devotion to the Divine), too, is also worth coming back to as a touchstone, a reminder that while on one level yoga is about uniting mind and body, it’s traditionally more about uniting our individual spirit or soul with the Divine.

If we bring these back to the center of our mats, we can be both more discerning about what is and is not appropriate and feel more confident in speaking out when lapses do occur.