On September 11, 1893, near the shores of Lake Michigan, the first ever Parliament of the World’s Religions kicked off at the Art Institute of Chicago.

In a written paper to promote the event, the organizers said it would aim “to unite all Religion against irreligion; to make the golden rule the basis of this union; and to present to the world the substantial unity of many religions in the good deeds of the religious life.”

All laudable goals, to be sure, the truth is they had very different intentions at heart. They really meant for the Parliament to be an exhibition of Protestantism, conveyed, more specifically, as what they labeled “Protestant Modernism.”

Though, at the time, Americans were rampantly proselytizing all over the world, the Parliament’s curators wanted to show that this newly packaged version of their religion was actually anti-colonial. That — having done comparative religious studies at the University of Chicago — they were, in fact, open to the ideas of other teachings, but based on objective analysis, Protestant Christianity was clearly the best of them all, especially in contrast to strange and exotic faiths like Hinduism, which was filled with primitive practices like idol worship.

When, therefore, a representative of the supposed “primitive” religion got up to talk, appearing anything but, the audience was viscerally awed.

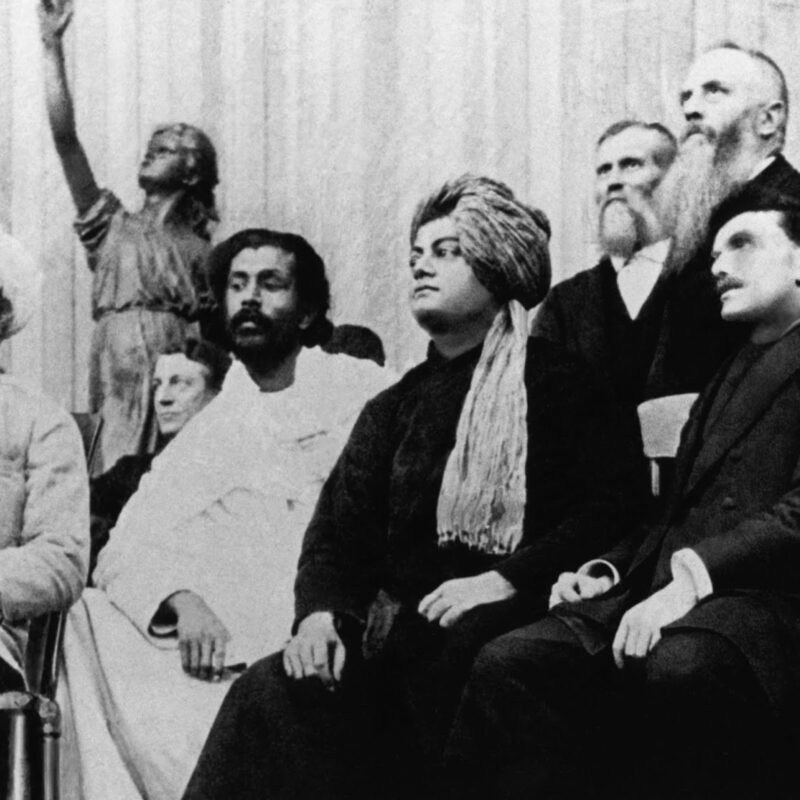

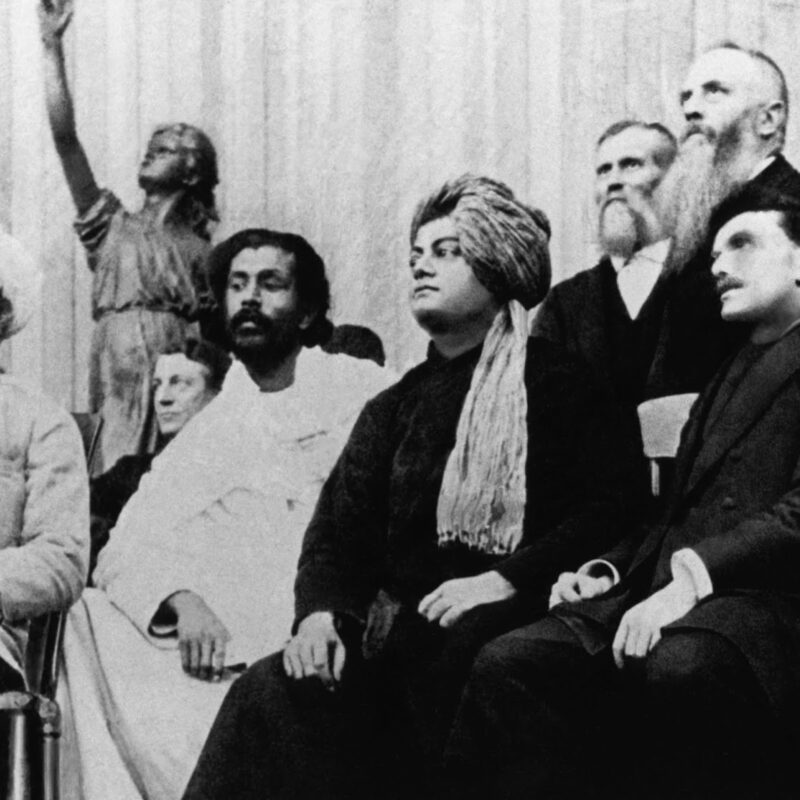

Wearing a flowing red turban complemented by yellow robes fastened with a scarlet sash, the 30-year-old Indian monk, exuding dignity and elegance, captured the attention of the 7,000 present, addressing them in astonishingly refined English.

“Sisters and brothers of America,” he began.

The words barely left his mouth before the crowd, which had remained all but sedate during the previous four speakers, suddenly rose to their feet and broke into wild applause.

Used to the formal, subdued, and even frigid mood in which the usual greeting of “Ladies and gentlemen” often set, the monk’s magnetic first words seemed charged with a heartfelt sincerity, and the listeners, who cheered for several minutes, truly felt it.

Despite his regal countenance, he had never before addressed a large gathering, and was initially nervous. Feeding off their energy, however, he continued in a spirited vehemence.

“It fills my heart with joy unspeakable to rise in response to the warm and cordial welcome which you have given us. I thank you in the name of the most ancient order of monks in the world, I thank you in the name of the mother of religions, and I thank you in the name of millions and millions of Hindu people of all classes and sects.”

Hinting at Hinduism’s illustrious and all-inclusive nature, he wasted little time as he then launched into just how venerable and encompassing this nature was.

“I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true. I am proud to belong to a nation which has sheltered the persecuted and the refugees of all religions and all nations of the earth. I am proud to tell you that we have gathered in our bosom the purest remnant of the Israelites, who came to Southern India and took refuge with us in the very year in which their holy temple was shattered to pieces by Roman tyranny. I am proud to belong to the religion which has sheltered and is still fostering the remnant of the grand Zoroastrian nation. I will quote to you, brethren, a few lines from a hymn which I remember to have repeated from my earliest boyhood, which is every day repeated by millions of human beings: ‘As the different streams having their sources in different paths which men take through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee.’”

A chord, one that hadn’t been touched for, perhaps ever, in America, was demonstrably struck, and the man who had done it was widely hailed as the undisputed star of the event. But who was he, and how had he come to be there in front of them?

Born Narendranatha Datta to an aristocratic Bengali family in Calcutta (now called Kolkata), his journey to the West begins with his upbringing, indelibly influenced by his mother, a devout and dedicated housewife, whose religious temperament fueled his own interest in spirituality, which manifested at an early age. Fascinated by wandering ascetics and monks, and disposed towards meditation even as a child, his interest continued through his youth, as he was attracted to many of Hinduism’s major texts, including the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and the Puranas.

Shaped simultaneously by the rational attitude of his father, who was an attorney at the Calcutta High Court, Narendra also had a deeply intellectual side, which he explored at length in college, studying Western logic, Western philosophy, and European history. Entrenched in the works of those like David Hume, Immanuel Kant, and Charles Darwin, his erudition and mental capacity amazed his teachers and mentors, earning him the status of genius by many.

Yet, as sense and logic very much made up the lens by which he viewed the world, garnering him respect, praise, and opportunities for its unique capacity, he remained unsatisfied. Still pregnant with the potent spiritual sentiments of his childhood, his soul yearned for something more and, as fate would have it, that something came when he met Sri Ramakrishna, an ascetic whose background was distinctly offbeat to the academic one he had grown accustomed to.

Holding no desire for education beyond the study of prayer and scripture, Ramakrishna was illiterate for all intents and purposes, engaging in behaviors unorthodox to the generally “sane” and “normal.” Besides performing the duties of his post as priest of the Dakshineswar Kali Temple, he spent a great deal of his time sitting or standing, regularly slipping into meditative states of “God consciousness,” subsisting on very little food or water.

While, upon meeting him, Narendra was averse to much of the religious orthodoxy connected to what Ramakrishna appeared to represent, he felt inexorably drawn to the saint, who indeed seemed to permeate a spiritual radiance, undeniable and electric.

And when he asked him, as he had numerous other teachers, if he had seen God, Ramakrishna gave an answer that resonated with Narendra unlike any he had heard up until that point.

“Yes, I have,” Ramakrishna said. “I see him as I see you, only in an infinitely intenser sense.”

As simple as it was bold, the reply presented spirituality as something more than just a mystical notion to be ethereally grasped at. It was a reality that could be tangibly perceived, harmonizing faith and reason in a way that heavily appealed to Narendra, who had spent his life teetering between both.

Hence taken by Ramakrishna, he frequently visited Dakshineswar, seeking the priest’s guidance more and more, eventually accepting him as his guru in a formal sense. Growing increasingly dedicated to his teachings over the years, Narendra helped to establish a new monastic order under his guidance, and took on the vows of a renunciate after his passing, ultimately assuming the life of a wandering monk.

It was during the early years of his monk period that a greater vision to share Hinduism with the world overtook him. Traversing his country by foot and railway, he experienced the land on a most intimate level, and on doing so developed immense sympathy for its people, the majority of whom were drowning in destitution — caused in no small part by the British, who had drained the once affluent region of its resources.

Discussing their conditions with others, he said:

“I have traveled all over India, but alas, it was agony to me, my brothers, to see with my own eyes the terrible poverty and misery of the masses, and I could not restrain my tears. It is now my firm conviction that it is futile to preach religion amongst them without first trying to remove their poverty and their suffering. It is for this reason — to find more means for the salvation of the poor in India — that I am now going to America.”

Believing in the universal message of his tradition, but also believing the economic conditions of the public had to be improved for it to be fully appreciated, he set his sights on the Parliament, thinking it would be the perfect place to capture the attention of those who had the power to effect such improvement.

And the perfect place it was, but only for someone like him who was uniquely equipped to bridge the cultural divide. Accepting, prior to his departure, a new name — Vivekananda, meaning “the bliss of discerning wisdom” — his talent to make India’s philosophical depth accessible to a foreign audience was immeasurably dynamic, propelling his mission in America to astounding triumphs.

Following his Parliament debut, America’s esoteric community took him in with open arms, facilitating a lecture tour throughout the US. Elaborating further on Hindu spirituality and its all-embracing proclivity regarding other legitimate faiths and sciences, he quickly attracted many followers, including the likes of writer Leo Tolstoy, actress Sarah Bernhardt, and philosopher William James (arguably the country’s premier intellectual at the time).

Taking advantage of the momentum, Vivekananda established The Vedanta Society of New York, where he held classes in meditation, before publishing Raja Yoga, his seminal book centered on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, Hinduism’s most popular text on yoga.

An easy-access guide to spiritual techniques, the work, emphasizing the sacred goals of yoga above just the physical postures, was a resounding hit, embedding Hinduism’s ancient culture in the fabric of America’s unlike it ever had been before.

Flushed with the success, he never forgot the dream to uplift the people of his own country, offering advice and financial support to his followers and brother monks from afar all the while. In 1897, roughly four years after he embarked on his epic journey to America, he took a giant step in making his dream come true, when he returned to India and founded the Ramakrishna Mission, a social relief organization named after his beloved mentor.

Along with the Ramakrishna Math, a legal entity formed a little later specifically for the purpose of training young monks in the duties and standards of its teachings, the Ramakrishna Mission is now part of a larger spiritual movement known as the Ramakrishna Order.

Containing hundreds of centers all over the world, some of which provided mentoring to prominent intellectuals like Aldous Huxley, Joseph Campbell, and J.D. Salinger, who helped prime America for the cultural revolution that led to the country’s booming interest in other religious practices, the order’s historical influence can’t be overstated.

Neither, thus, can that of the first Parliament of the World’s Religions, whose purported objective was emphatically achieved, cementing its legacy as the birthplace of the worldwide interfaith movement.

But, of course, only so much of the credit can go to its organizers. Its true hero was Vivekananda, India’s trailblazing ambassador — the proud Hindu.

If you enjoyed this piece, then you may also be interested in reading “Journey on the Jaladuta: How a cargo steamship brought bhakti yoga to America”