To stay abreast of the ins and outs of the Hindu world, I subscribe to a news service called Hindu Press International or HPI. HPI sends out daily digests of stories from India and around the world about Hindus and Hinduism. Most days, I quickly scan the short blurbs which cover a variety of stories — from detailed holiday celebrations in Mauritius to violations of Hindu human rights in Kashmir; discoveries of ancient ruins in Cambodia to the inauguration of a new temple in some remote corner of the world. Indeed, many of these stories are enlightening, but a particular story last year brought a huge smile to my face and a moment of connection to the shakti that manifests through every woman around the globe.

Here’s an excerpt:

“A group of women activists, belonging to Maharashtra’s BJP Mahila Morcha, created history on Wednesday by storming into the sanctum sanctorum and performing puja at the famous Mahalakshmi temple at Kolhapur in western Maharashtra, where only men are allowed to enter the “garbha-griha” … as many as 20 activists, led by State BJP Mahila Morcha chief Neeta Kelkar, took the temple authorities by surprise by entering into the sanctum sanctorum of the Mahalakshmi temple …

The women activists not only ignored the persistent efforts by the priests and police personnel present to prevent them from entering the ‘garbha-griha’, where the temple management has over the years steadfastly disallowed the entry of women, but they also dressed the presiding deity with a new saree and performed puja.”

Perhaps there were more diplomatic, less political ways of gaining access to the heart of the temple, a space which in the past was not closed off to women. But shakti takes form in unpredictable ways. Since Vedic times, the Hindu tradition has personified shakti, or the Divine power by which all is created or changed, as feminine, hence the central role of Goddess or Devi in our understanding and worship of the Divine.

Shakti is quiet yet strong, loving yet tenacious, graceful yet fierce, creative yet capable of unmatched rage. Hindu society, however, a primarily patriarchal society, has always elevated only the softer virtues of shakti in defining the “ideal woman.” But at the deepest levels of our collective conscience, I believe that we all know that it is the compassion and benevolence inherent in the feminine that compels woman to exercise restraint in displaying the enormity of her fierce strength all at once and only when needed.

Indeed love, compassion, nurturing, selfless service, grace, deference — so much a part of the essence of womanhood — have served as the unbreakable threads which hold together healthy families and societies. But where has the privileging of only our softer side left the fabric of not only womankind, but mankind? Has it opened us up to a vulnerability that is harmful? We cannot deny that in the past century, many women world over have made remarkable progress in the secular — ie. educational and economic realm, but about the socio-religious realm? Can we deny that in India and even here in our communities, many of our sisters are not free to feel they are not a burden on their family, not free to think independently, not free to marry based on a meeting of minds, not free to leave abusive relationships, not free to pursue creative passions, not free to participate in certain prayers or sacraments, not free to just be?

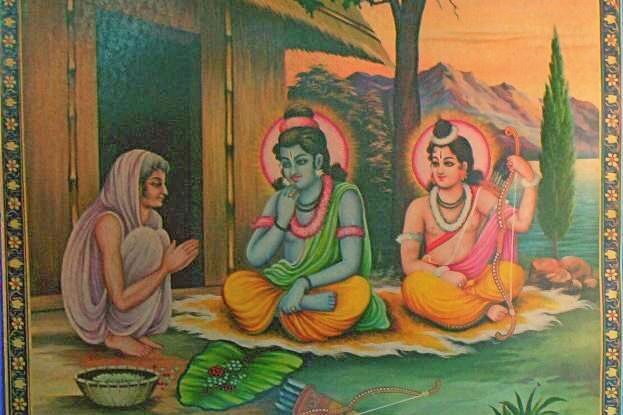

In order to know where we are today, we must know where we’ve been. Our scriptures, while they offer ample Hindu “his-story,” also give pearls of “her-story.” Vedic times hosted the exemplar of Hindu femininity: women who were both Sadhyavadhu, or those who take up the responsibilities of family life, and Brahmavādini, or those who dedicate their lives to the study of the Vedas and Self-Realization. There were also those who forsake convention and chose only the austerities of the latter. The Vedas are also replete with hymns extolling the spiritual sameness or equal standing of male and female deities while highlighting their differences in nature. Many themes center around courtship and marriage, while others focus on philosophical and educational engagement. Thus, the timeless role of male and female, whether divine or mortal, is supposed to be one of setting aside innate differences and coming together for social and spiritual fulfillment — two halves of a whole or two wheels of a cart, pulling their weight in their own respective ways to move the cart forward.

Equal not opposite. Equal but different. Equal, complementary, and supplementary. Within this framework, the traditional social role for woman was the revered caretaker of the home, provider of selfless love and emotional support, nourisher, moral pillar, and keeper of the home altar and familial religious observances. Somewhere along the way, though, sadhyavadhu took over, burying brahmavādini deep into the annals of Vedic history. We’ve also seen that with the delusion caused by power, greed, envy, and other vices, as well as increasing Westernization, respect and appreciation for stay-at-home mothers and wives went from overflowing to ebbed.

Over the past few millennia, and like women in other cultures, we’ve been falsely judged as weak, simple-minded, dependent, attached, irrational, unworthy, or impure and relegated to roles that reflect these negative stereotypes. As a result, many of our foremothers’ lives and choices were shaped not by inspiration, but expectations. And to be fair, many of these expectations were imposed on them by other women. The unique travesty for Hindu women, however, is that many of the socio-religious practices and attitudes that have quelled womens’ destinies for something greater, something higher are in direct opposition to what the Vedic woman stood for — that is the essential Hindu teachings of our inherent divinity, our equal potential for Self-Realization, and the mandate that we live life according to dharma.

But on many an occasion, women throughout Hindu history have demonstrated their ability to stand up to the status quo, to right wrongs, or to simply lead the way, and have done so with elegance and humility. These courageous women have spanned the ages, from as far back as the time of the Vedas to, well, last year.

Of the 407 sages to whom the eternal Truths were revealed in the Rg Veda, 28 were women — the great Gārgi being one of them. She is credited for having brought out the answer to the most profound questions of Vedanta — the nature of Brahman and the origins of the Universe. During a public debate with Sage Yajnavalkya as chronicled in the Brhadāranyaka Upanishad and in a court filled with male philosophers, Gargi fired question after question at the great sage, stumping a man who had never before been stumped. At one point Yajnavalkya even warned Gargi that her head would fall off if she continued, so she humbly stepped aside, in the hopes that others would continue where she was leading the sage. Others piped in, but failed to elicit the answer she was clearly aiming for, so she spoke up one last time. It was her final two questions that led the great Sage to definitively articulate the nature, or lack thereof, of the unmanifested, unknowable, formless Brahman.

In the Middle Ages there was Mirābai, who fought the conventions of royal life and against what was considered “appropriate” behavior for women of the time. A prolific bhakti poet-saint, Mirabai was the first of religious freedom advocates. She rebelled against her in-laws by continuing to worship Lord Krishna, the deity of her childhood, rather than being forced to pray to the deity of her new family. Later, she would escape several attempts on her life by her in-laws because they did not approve of her very public practice of religion. Imagine a princess singing and dancing with abandon, and that too amongst other Krishna devotees, including commoners. She rebelled against societal norms and tradition to pursue her life’s one focus — selfless surrender to God.

Others have graced the pages of more recent history like Jhānsi ki Rāni. Lakshmi Bāi, her given name, had humble beginnings. The daughter of a priest, she was trained in the art of warfare as a result of her father’s influence with the royal court and perhaps too because of his open-mindedness. At the tender age of 14, she was married to the King of Jhansi, but was quickly recognized for her inborn leadership skills. Long acknowledged as a key player in one of the earliest battles in India for Independence from the British in 1857, she died a fearless warrior on the battlefield, sword in one hand, reins in the other, fighting for the freedom of her kingdom and her people.

And today we have amazing women like Mā Yoga Shakti, the adopted guru of my husband’s family and a person with whom I have had the honor of spending time. They, amongst others, in following a higher calling, has entered the traditionally male-dominated world of Hindu ascetics. is an embodiment of maternal and wisdom-filled love to all those who approach her. But unlike many other monks who are part of a larger sampradaya (tradition) or guru-shishya parampara (teacher-student lineage), she has tread a path of her own — inspiring, educating, and counseling thousands of souls along the way in a distinctly feminine way.

At the risk of being accused of judging the relevance of these remarkable women through a western feminist lens (after all I was born and raised in America and despite all my best efforts to balance East and West) I see their tenacity, not so much as a quest for equality, but a quest for freedom — the freedom to question, the freedom to think, the freedom to worship, the freedom to experience — which I believe is the amruta or nectar of our tradition.

On their journeys, they’ve also toppled many of the assumptions about women imposed upon us by both men and women or sanctioned through religion — that we’re incapable, we’re weak, or we’re impure.

There are so many others, who while their acts were significant, their reach went only as far as those who personally knew them. My paternal grandmother who lived with us from even before I was born, was to me the epitome of Shakti in all Her forms. Widowed at the young age of 35 with five young children, she defied the village women who quickly arrived upon my grandfather’s death to tell her what she could and couldn’t do. She only knew what she should and had to do.

She was no stranger to tragedy: she had lost her own mother at the tender age of two. Her grade school education abruptly ended when she was married to my grandfather after his first wife, her cousin, died. Grounded in her faith and understanding of the Gita, which she read almost every day of her adult life, she never once asked, “Why me?” and only resolutely fulfilled her dharma. She not only saw that her children survived, she saw that they flourished. Selling jewelry to survive and managing what little finances they had like a seasoned CFO, she prioritized the education her children and the inculcation of the highest of Hindu values. My father and his brothers, studied hard and worked hard and earned scholarships to study in a America, and the rest as they say is Hindu American history.

There have also been men who have broken barriers for women. Right in my own family, we had the example of my paternal grandfather. A Gandhian and freedom fighter, he was committed to educating both his sons and daughters, in spite of very limited means. He sent my aunt and mother from their small town of Jhalod to the big city of Baroda to MS University to pursue their college education. Later when my aunt was accepted at Penn State to pursue her graduate studies, he sent her against the gossiping whispers and finger-pointing naysayers in town. My aunt became the first girl to go to America from Panchmahal district in Gujarat in the pursuit of graduate studies.

And during Navratri, the Festival of the Mother Goddess, I cannot forget the example of my own mother. Even though higher education was prioritized, she grew up in a way in which it was expected that a child respectfully and dutifully follow certain religious traditions, and yes, taboos, without questioning why. As rebellious American-born Hindu teenager, this formula was not going to work. For a few years, in fact, I’m sure my parents thought that “Why” and “How come” were the only words in my and my sister’s vocabulary. But instead of discouraging our questions or predicting all calamity of our ill-fated, non-believing futures, my mother set upon her own quest to finding out why. If she didn’t have the answers, she would get them for us. So began our balavihar days at Chinmaya Mission. Today, my mom, now a grandmother of four, is not shy or self-conscious about revisiting many of the traditions and rituals of her youth to find out why we do things the way we do, contemplating on the answers, and absorbing only that which is in accordance with her Self-Awareness. As a result, I can say confidently that she, my sister, and I are now devout Hindus not because we have to be, but because we want to be.

It is all of these trailblazing women and men — their curiosity, their bravery, their fortitude, their bhakti, their shraddha — that inspire my work at the Hindu American Foundation. The Hindu American Foundation is a national advocacy organization seeking to provide a voice to the Hindu American community. I am one of HAF’s co-founders and nearly ten years ago, little did I know I was entering male-dominated territory, albeit new territory for our community — that is the world of Hindu American advocacy. During HAF’s early days, I was the sole woman amongst five men — one of those being my husband, which sometimes presented its own challenges. But all of them were open to my opinions, respectful of my instinct, supportive of my leadership, surprised by my strength, and sometimes awed by my ability to multi-task — presenting draft bylaws for the newly forming HAF while at the same time preparing palak paneer and paratha for the Board meeting.

From volunteer, I shifted to serving as HAF’s full-time Executive Director and Legal Counsel nearly five years ago. Today, half of both staff and our Executive Council are female, so as the saying goes, “We’ve come a long way, baby.” Yet every so often, my colleague and dear friend Sheetal Shah, HAF’s Senior Director and force behind our Take Back Yoga campaign, roll our eyes when we get letters or emails to Mister Suhag Shukla or Mister Sheetal Shah — this too after this campaign to shed light on yoga’s Hindu roots made it onto the New York Times, CNN, Washington Post, and NPR. It could well be an innocent mistake — after all, the two of us do have kind of androgynous names. But once in awhile our most agitated suspicions are confirmed when we bump into an uncle or auntie at an HAF program who says, “Oh I had no idea you were a woman. I just assumed by your forceful work that you were a…” The fact is that at HAF, we are women and men working side by side for the greater good of Sanatana Dharma. We are striving to utilize and maximize our different strengths to create an environment in which Hinduism can truly be understood so that all of our children can hold their heads high as Hindu Americans. HAF has taken a Hindu voice to the U.S. Supreme Court and the U.S. Congress, to hundreds of news media outlets and all across America generating awareness and educating Americans on what Hinduism truly is.

The most rewarding aspect of my work at the Hindu American Foundation has been the opportunity to stand up for religious freedom — whether for Hindu Americans or other Hindus around the world. HAF has provided a platform from which to take a Hindu voice to courts across the nation. We’ve offered a Hindu perspective on issues such as the constitutionality of a taxpayer funded Christian license plate, a city council allowing only Jews and Christians, but not pagans or Hindus, to offer prayer at public meetings, or a state prison denying a Hindu inmate vegetarian food. I’ve had the chance to challenge Christian leaders and members of our government on spiritual, familial, and societal violence caused when missionaries distribute desperately needed humanitarian aid in villages throughout India — be it medical care for a sick spouse, education for a young daughter, or food to feed their impoverished family — only if the recipient converts. The conversations are often tough, but I have definitely used to my advantage, what I believe are uniquely feminine skills of delivering a hard punch with a kid glove.

HAF has allowed me to give voice to our Hindu sisters around the world, especially in Pakistan, Malaysia, and Bangladesh, who suffer unimaginable horrors simply because of the fact that they are Hindu and female. In Pakistan’s Sindh province, 20-25 Hindu girls are kidnapped a month and forcibly converted to Islam and married off to Muslim men. If they are not married off to complete and often times, far older strangers, they are beaten, maimed, raped, gang-raped, sold off, or thrown into prostitution. Some of you may have heard of such a case involving a young Hindu girl named Rinkle Kumari. Unlike most Hindu kidnapping cases, hers actually went as far up as Pakistan’s Supreme Court. Despite the heartbreaking pleas by both Rinkle and her parents, the Court forced her to return to her kidnapper cum husband.

As women, our roles as daughters, sisters, wives, and mothers, allow us to experience a more empathetic compassion for Rinkle, her mother, and the far too many others. That is why it is critical for women like us, who are fortunate to be living freely in this thriving democracy and who have the benefit of knowing about the many fierce Hindu warrioresses before us and amongst us, to stand up and speak out for those who can’t.

Will Neeta Kelkar and her 19 sakhis, who barged into the Mahalakshmi temple over a year ago, or the countless women around the world who are compelled to let their full-form shakti arise from time to time, make the kind of history other great women have before them? Only time will tell. Nevertheless, I am inspired to continue marching forward while drawing strength from our Vedic past. And I will always be inspired by the many ordinary and extraordinary women who have brought about change, bucking many a man-made traditions, one graceful step at a time.