American pop culture has become progressively steeped in Hindu influence over the years, and you’d think we who adhere to the religious tradition would be nothing but elated about it.

The truth, however, is a little more complicated. Indeed we love that the Western world is taking to the spiritual themes, concepts, and practices Hinduism has to offer. We just have mixed feelings about how some of them are being framed. While a number of examples can be highlighted to convey these feelings, one stands out as especially emblematic, for it can be found at the heart of Hollywood, garnering the passion of its elites.

I’m talking about Transcendental Meditation, a practice Hugh Jackman said changed his life, that Katy Perry called a cure for stress, that Jerry Seinfeld described as a charger for the body and mind, and Martin Scorsese proclaimed a godsend. A practice that is wholly and unequivocally Hindu, but never presented as such, at least not in the mainstream.

Why?

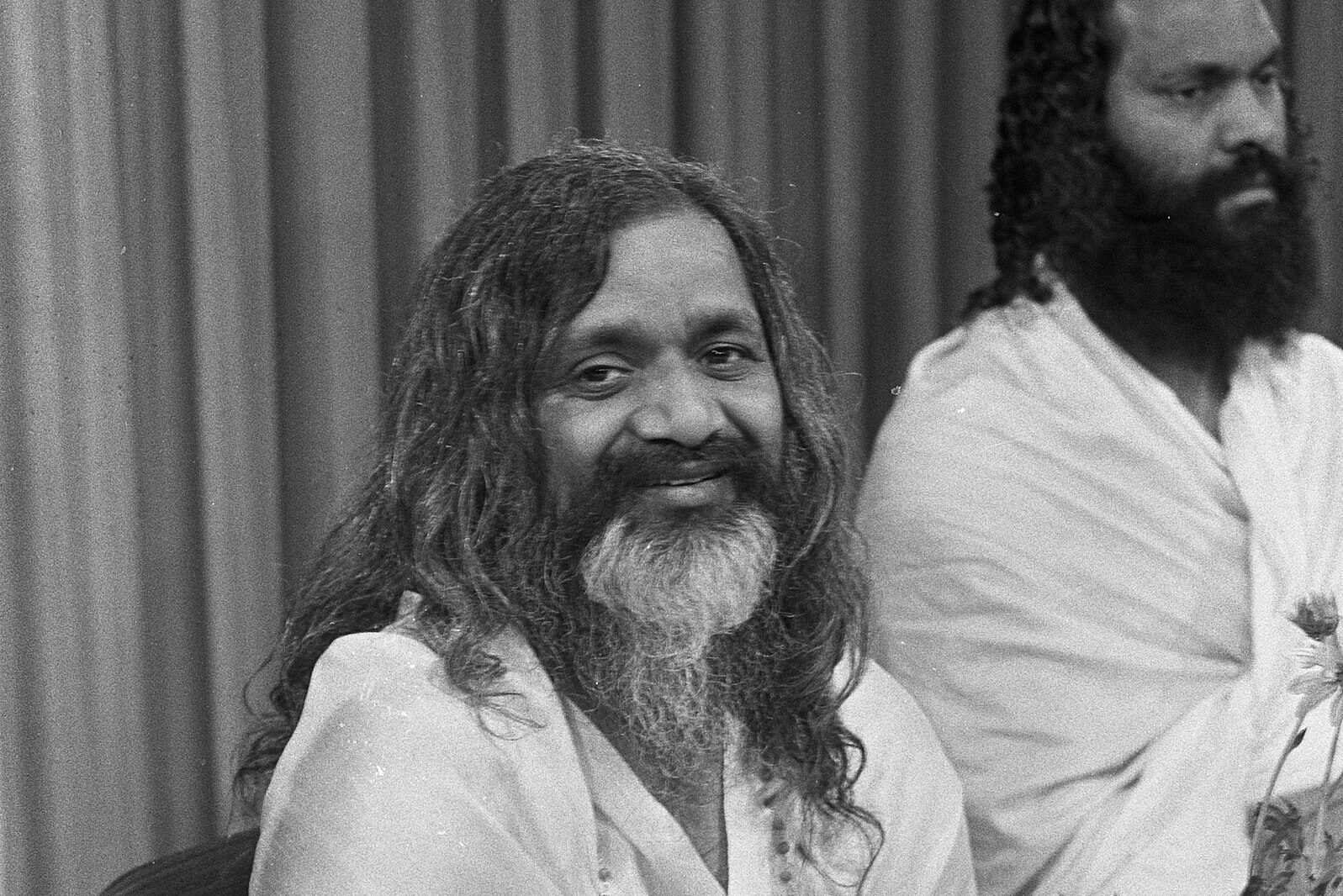

The answer to this question — or at least one that offers a more nuanced explanation beyond the sweeping and excluding nature the stamp of cultural appropriation often has attached to it — opens with the man who brought TM to America in the first place: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

Born in the first quarter of the 20th century (varying years are given for his birth) in Central India, his journey as an ambassador of meditation was sparked during his college years, while attending Allahabad University.

Pursuing a degree in physics, he simultaneously started learning Sanskrit and yoga under Swami Brahmananda Saraswati, a guru in the lineage of Adi Shankara, Hinduism’s great exponent of the Advaita Vedanta system, which emphasizes the eternal divine oneness of all above the temporary worldly differences that separate us.

Developing a close bond with his mentor, who he came to affectionately call Guru Deva, Maharishi, upon completing school, joined him at his retreat in the Himalayas, where he spent more than a decade deepening his spiritual knowledge and practice, studying a medley of India’s major philosophical works.

It was in the course of this period, as he fully dedicated himself to an ascetic discipline in pursuit of enlightenment, that he had a realization: some aspects of this discipline could be used and benefited by any person, regardless of lifestyle.

Sure, spiritual progress, like any lofty goal, requires sacrifice and dedication, but too much prematurely is never encouraged, as it can lead to frustration, resentment, and ultimate regression. As explained in the Bhagavad Gita, one of Hinduism’s most popular texts, which Maharishi had grown distinctly fond of, all individuals, according to their nature, have a unique path. Albeit different, these paths, when followed sincerely, can all guide one towards the Divine, just as different paths on a hill, when treaded faithfully, can lead one to its peak.

In other words, just because the life of an ascetic isn’t meant for everyone, doesn’t mean spiritual practices aren’t too. All are on a sacred journey in some way, shape, or form, so all have a right to techniques that can help bestow inspiration and advancement on these journeys.

As it happened, Maharishi believed his tradition offered one that was markedly simple, potent, and highly accessible. One that could uplift people of all backgrounds, no matter who they were or where they came from. One known as mantra meditation.

With man meaning “mind” and tra meaning “to deliver,” mantras are sacred vehicles of sound vibration which, when uttered in repetition, are said to carry us past the volatility of the mind to a transcendent state of awareness, where we can perceive Divinity’s underlying presence, filling us with peace, love, and spiritual energy.

The committed often spent hours at a time chanting mantras. But Maharishi thought 20 minutes twice a day would be enough that those immersed in worldly life could still reap its rewards without feeling overburdened by the process.

Thus, in the years following the death of his guru, he launched a global campaign to disseminate his easy-to-adopt version of the technique — dubbed Transcendental Meditation, a non-sectarian practice for the masses. Stripped of all its Hindu packaging, he presented TM on multiple world tours in the early ‘60s, finding a wide audience in a young and disenfranchised generation seeking a spiritual path free of the religious stringencies they were brought up under.

When, in 1967, the Beatles, who in numerous ways led the charge towards this path, famously went to his ashram in Rishikesh to learn TM from him personally, his audience grew even wider, creating a buzz that drew international attention.

Capitalizing on the boosted interest, Maharishi swiftly began connecting with academics to study TMs potential health benefits, an endeavor that proved to be incredibly fruitful, leading to more than 380 peer-reviewed research studies published in upwards of 160 scientific journals over the subsequent 50 years.

Yet, as his goals evolved perpetually larger, comprising utopian visions and increasingly hard-to-believe claims about the practice’s supernatural effects, and it eventually came out the Beatles left his ashram in a level of discontent, TMs popularity deflated.

By the ‘80s, all that remained, more or less, was a small devout community based in a corner of southern Iowa, and the Maharishi, who stopped making public appearances, resigned to spending most of his time at an isolated compound in the Netherlands.

Needless to say, this wasn’t the end.

In 2002, after barely being seen in public for years, Maharishi offered followers what was called the Enlightenment Course, or the rare chance to spend a month with him in Vlodrop.

A hefty $1 million fee to join, director David Lynch was among the 150 who bit at the opportunity. Yes, as someone who had been spending his days making lots of money, marrying multiple women, and filming violent movies, he seemed like an atypical aspirant, in truth, he held a deep love for meditation, and was excited at the prospect of reveling in the personal eminence of its ambassador.

And though his excitement wavered once he discovered that Maharishi didn’t actually attend the meetings but interacted via a teleconference system, it was quickly reinvigorated. The experience, in fact, proved to be one of the most profound of his life.

Returning to his home in Los Angeles a changed man, Lynch, imbued with an impassioned desire to share his experience with others, put his career in the peripheries of his focus. Publicly announcing his support for TM and Maharishi’s agenda for world change, he soon established the David Lynch Foundation which, in its genesis, set out to improve the lives of troubled children through meditation.

Ambitious in his aim, it wasn’t long before he expanded on the idea, embarking on a two-year speaking tour through over 30 countries in an effort to raise $7 billion and spread the positive impacts of meditation ever further.

Since the commencement of his crusade, those learning the technique have risen at least ten-fold, encompassing not just children, but a wide demographic spectrum, including young adults — a good deal of whom grew up meditating — and veterans suffering from PTSD.

Of course, the foundation’s more conspicuous impact has been made with the explicitly renowned, due, in large part, to its CEO, Bob Roth. Coming off decades of work for the Maharishi prior to assuming the role, he has spent much of his time traveling the world, promoting TM in consort with some of its now most prominent advocates, like Gwyneth Paltrow, Ellen Degeneres, Howard Stern, Clint Eastwood, and the already mentioned Perry, Seinfeld, and Jackman.

Thanks to their help, today TM, as the Maharishi intended, is in the mainstream. So much so, that after his death in 2008, he himself has faded immensely from its branding, leaving little trace of what Hindu vestiges remained attached to it. For many, this is a good thing, because it allows the practice to be freely accessed without any sort of religious blocks.

But for us who know anything about the religion it came from, it’s poignantly ironic. A pluralistic tradition, Hinduism’s practices never had any blocks to begin with. They’re open to all, provided they’re approached with honor, respect, and candid sincerity.

If you enjoyed this piece, then you may also be interested in reading “Buddhist mindfulness is all the rage, but Hinduism has a deep meditation tradition too”