I often compare Swami Vivekananda to Jackie Robinson, the first African-American player to break through the color line of Major League Baseball.

Like Robinson, Vivekananda shattered barriers, overturned misconceptions and stereotypes, paved the way for others like him, and established a template for future progress.

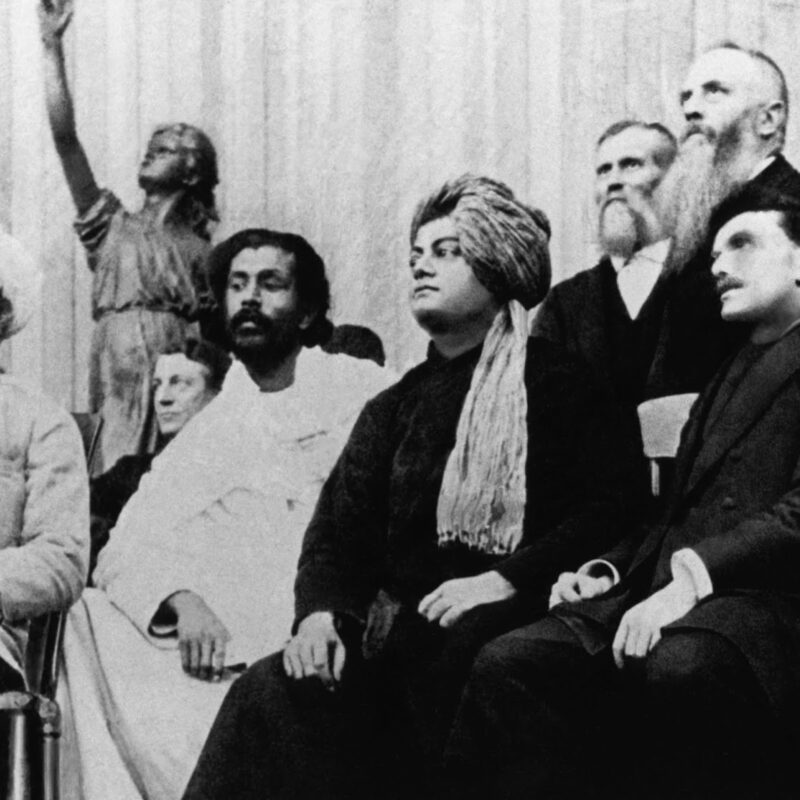

At the time of Vivekananda’s historic triumph at the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions, few Americans had even met a Jew or a Muslim, much less a Hindu monk in orange robes and a turban (pictured second from the right in the photograph above).

India was perceived by most as a backward outpost of the British Empire, and Hinduism as a primitive, polytheistic, idol-worshiping religion in need of Christian missionaries.

Vivekananda’s erudition and command of English would have been startling enough, but it was the content of his speeches that really blew minds.

In his short, famous opening talk, he described Hinduism as “a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance” and accepts “all religions as true”; and presented the core Vedantic proposition that all paths ultimately lead to the same pinnacle of spiritual realization, citing the Bhagavad Gita: “Whosoever comes to Me, through whatsoever form, I reach him; all men are struggling through paths which in the end lead to me.”

With the notable exceptions of those familiar with early adopters of Hindu Dharma such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and his fellow Transcendentalists, as well as the emergent New Thought movement, these points would have been eye-opening. They turned conventional religion around 180 degrees, from dogma and belief to inner awakening; from triumphant exclusivity to inclusivity; from conflict with reason and science to compatibility.

It was a vision of Unity amidst diversity, amplified by a fervent denunciation of all religious fanaticism, and of the Christian missionary effort in India.

He also took on the Christian notion of original sin. It’s a sin to call people sinners, he said, offering in its place what might be called “original ananda”— a fundamental shift in the understanding of our true nature and our relationship to the Divine.

Vivekananda’s message was welcomed enthusiastically by open-minded American seekers — and scorned by conservative Christians, including some of the Parliament organizers whose agenda was to demonstrate that Protestantism was the pinnacle of religious progress.

No doubt to their dismay, word of mouth and adulatory press coverage made Vivekananda the star of the show.

He spoke several more times in the course of the 16 days, sometimes giving the same talk back-to-back to accommodate the overflow crowds. Indeed, if not for the Hindu emissary the Parliament might have been forgotten by history instead of being credited with launching the modern interfaith movement.

Thanks to that public reception, Vivekananda stayed long enough to ignite the East-to-West transmission that has reshaped America’s spiritual landscape.

His time here totaled less than four years in two separate visits, with time in India in between (where he was greeted as a national hero). He toured much of the US, bringing the modern Vedanta he honed after his formative years with the Brahmo Samaj in Calcutta and at the feet of his legendary master, Sri Ramakrishna. From the start, he knew how to shape his message in a way that appealed to modern Americans who valued rationality, pragmatism, and science.

Like Mozart, Gershwin, and other shooting stars who never reached the age of 40, Vivekananda left behind a remarkable legacy when he passed, in India, on July 4, 1902.

In his voluminous writings, he articulated the essence of Vedanta. His slim books on the four principal yogic pathways — karma, jnana, bhakti, and raja — became the authoritative descriptions of those spiritual orientations, and they remain so to a large extent to this day.

He trained disciples to carry on his work and created an institutional structure to perpetuate it. He opened the first Vedanta Society in New York in 1894, and over time centers were established in most major cities. To this day they are run by swamis trained at the Ramakrishna Math and Mission, about ten kilometers upriver from what is now called Kolkata.

Millions have been profoundly influenced by Vivekananda’s work, and many of them, if not most, have no idea who he was.

They may have picked up the essence of Vedanta as Swamiji formulated it from one of many indirect sources: a self-help book by a psychologist; the chatter at a yoga class; a book by prominent intellectuals such as Aldous Huxley, Christopher Isherwood, Joseph Campbell, or Huston Smith, all of whom were mentored by Vedanta Society swamis; in The Varieties of Religious Experience, the seminal study by William James, who got to know Vivekananda in Cambridge and drew from his Raja Yoga; in the work of famed novelists like J. D. Salinger, a devoted student of Swami Nikhilananda in New York, or even Henry Miller, who was best known for risqué fiction but opens his nonfiction book, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare with a full page of Vivekananda quotations. Miller said, “Swami Vivekananda remains for me one of the great influences in my life,” and Salinger has one his characters call him, “one of the most exciting, original, and best equipped giants of this century I have ever run into” adding, “I would easily give 10 years of my life, possibly more, if I could have shaken his hand.”

Or maybe they heard that George Harrison, “the quiet Beatle,” had his life turned around when he read Raja Yoga on his first trip to India, in 1966. Harrison said of that experience, “Right on the inside of that book cover [Vivekananda] said, ‘If there’s a God, we must see him, and if there’s a soul we must perceive it. Otherwise, it’s better not to believe. It’s better to be an outspoken atheist than a hypocrite.’ Then, on reflection, I realized that the Christianity that had come in my life as a child was all this idea that you’re never going to see Him. It’s like hypocrisy, in a way. That’s why I wrote in My Sweet Lord, ‘I really want to see you,’ because if there is a God, I want to see him. I don’t want to just hear some holy roller shouting about him. Through the Indian philosophy and all that I came into contact with, it just showed me that it’s actually inside. He lives in our hearts.”

Many of those American yogis and Vedantists who never heard of Vivekananda followed, or learned from, one of the gurus, swamis, and yoga masters who brought India’s treasures to the West. Every one of them was, at the very least, inspired by Vivekananda’s groundbreaking work, and whether consciously or not, they followed his template for skillfully adapting their teachings to the rational, pragmatic, evidence-based, English-speaking world — and to do so without distorting or diluting the integrity of Sanatana Dharma.

This is especially true of Paramahansa Yogananda. In writing a biography of that hugely influential teacher (who was born the year of that historic Parliament), I learned how profoundly he was influenced by the legacy of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda during his formative years in early 20th-century Calcutta.

For the past few decades, surveys have shown that an ever-increasing number of Americans see the world in a manner consistent with the core precepts of Hinduism.

They recognize the essential unity that underlies and permeates the diversity of the manifest world; they know that the same divine essence dwells within every human being; they seek to realize and express that reality in their lives; and they acknowledge that there are many pathways to realization and no one path is right for everyone.

This can be seen as a direct outcome of Vivekananda’s foundational work and the myriad streams and tributaries that branched out from that auspicious beginning.

Not only should his birthday, January 12, be celebrated each year, but so should the date of his opening speech at the 1893 Parliament: September 11. It would be a sublime way to balance the remembrance of the horrors committed 108 years later by the religious fanatics he deplored.

Philip Goldberg is the author of numerous books, including American Veda: From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation, How Indian Spirituality Changed the West; The Life of Yogananda: The Story of the Yogi who Became the First Modern Guru; and most recently, Spiritual Practice for Crazy Times: Practical Tools to Cultivate Calm, Clarity and Courage.