What was life like before Partition?

I was 13 and have no memories of the political situation at the time, but I remember it being generally quite peaceful in Sindh before Partition. There were no riots, communal tension, etc.

How would you describe the period directly leading up to the Partition?

For a few years before Partition, some news of the Hindu-Muslim rift started brewing. Feeling that too much economic and political power was in the hands of Hindus, the local leaders of the Muslim-majority community in Sindh began arousing communal passions. Prior to this, there had actually always been peaceful accord between the two communities.

The news of riots in Punjab and Bengal further aroused tensions later on. Towards the end of 1947, soon after Partition, the atmosphere started getting tenser, even in an otherwise peaceful Sindh. Riots occurred in Karachi and a few other places. It was then that most Hindus in Sindh decided to migrate to India.

What feelings and images come to mind when remembering Partition itself?

I was only a young teenager, but I do remember most of the situation as it happened. Soon after Partition, there was an influx of Muslim refugees from India, and the tensions started. Though Sindhi Muslims had always maintained cordial relations with Hindus, many of these Muslims developed prejudices, coupled by a greed to acquire the boons of wealth and properties left by the Hindus who fled. But alas, most of this wealth was grabbed by the more muscular and dominant Muslim refugees who migrated from India.

When and how did you leave your home? Did you or any family members live in refugee colonies, and if so, what was that like?

We left in November 1947. Our family was large — consisting of my grandmother, two parents, and their five children (of which I was the eldest) — and we had to stay for a week on the Alexandra Dock in Mumbai. It was quite the experience, living out in the open, surrounded only by the meager luggage we were able to carry with us.

During that time, all our meals were provided for us by some government/volunteer agency, except for one time when my father managed to take us for lunch at a nearby restaurant, where we got a couple chapatis worth a few pennies to go along with some free dal.

Fortunately, after the week, my father, who was a railway employee in Sindh, was given a posting, along with a place to live (a small one-bedroom flat), in Ahmedabad. So we were lucky in that we didn’t have to stay in any refugee camps.

What was it like rebuilding your life? What of everything you endured during that period was the most challenging?

It was certainly very stressful to start a new life with a fairly big family and limited income, but compared to most others, it was not so bad. I think getting the one-bedroom flat was itself a big boon, considering so many others had to languish in refugee camps for years!

How did the challenges of that period differ from the older generation to the younger? (In other words, how was it different for you versus your parents or grandparents?)

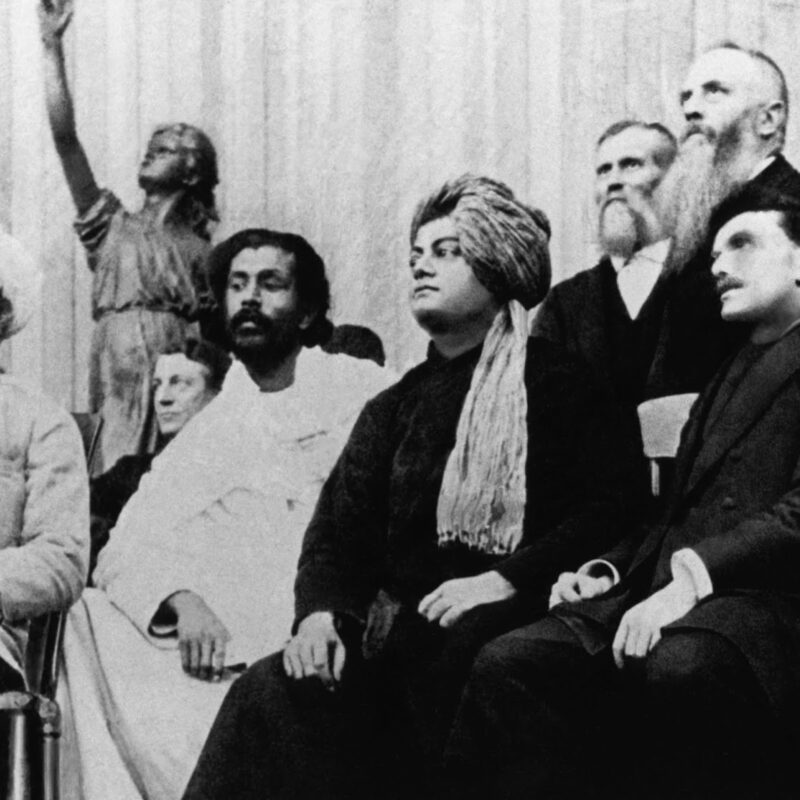

In August 1947, after some 300 years, the British finally were forced to quit India, and the subcontinent was subsequently partitioned into the independent nations of Hindu-majority but secular India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

After World War 2, bereft of the resources required to retain the jewel of its empire, which was growing increasingly unstable amidst India’s desire for independence coupled with the Muslim League’s push for a separate Islamic state, Britain’s exit was rushed, reckless, and woefully executed. Using out-of-date maps and census materials to create the new borders, which awkwardly split the key provinces of Punjab and Bengal in two, Partition triggered one of the largest mass migrations in human history, as the chaos, violence, and brutality that ensued swiftly spread, forcing millions to flee from all over, including provinces like Sindh and the North-West Frontier. Resulting in millions killed, millions more displaced, and some 100,000 women kidnapped and raped, the event is undoubtedly one of the worst to have ever taken place, though somehow it is yet to be recognized as such.

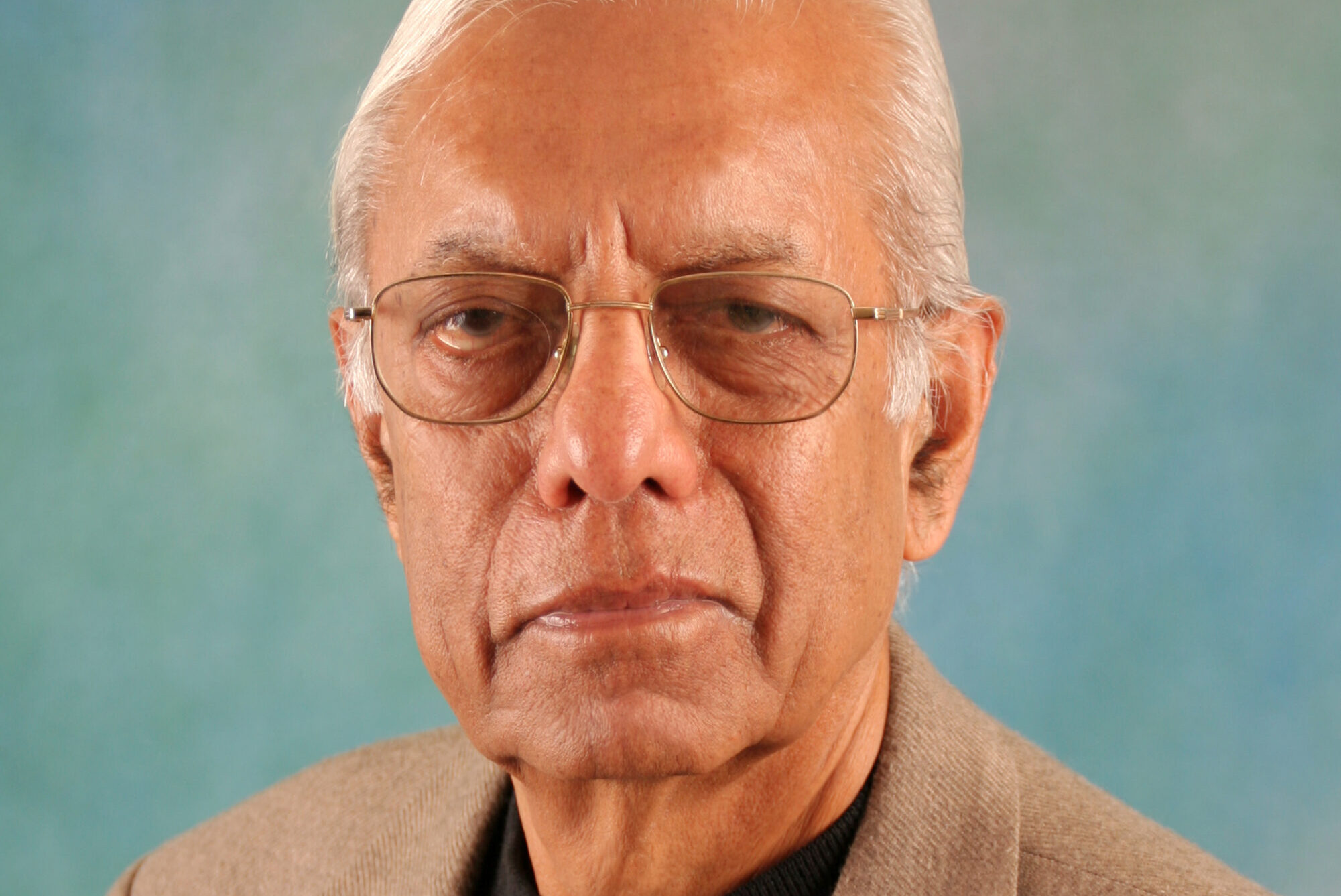

Among those wanting to change this fact is Dr. Hiro Badlani, who fled with his family from their home in Sindh after violence overtook their community. Eventually settling in Mumbai, where he practiced as an ophthalmologist for over 40 years, he now lives in Los Angeles, where he devotes his time to the study of Hinduism. Having written four books on the topic, he hopes to shed light not only on the beauty of its wisdom and practices, but on the journey of its followers and the struggles they have endured.

As I was the eldest among the children, I soon realized the challenges my father was facing — all centered around supporting a large family with a very limited income — and so tried to help in whatever ways I could. This usually meant doing family chores, especially ones that might help relieve the financial burden. I would, for example, travel a long distance on foot every day just to save a few pennies on milk, vegetables, and other such items.

Despite the fact relations varied considerably by region and by ruler, Hinduism and Islam managed to exist alongside each for close to a thousand years in India up through the 19th century. What, in your eyes, caused these relations to deteriorate so immensely in the two-decade period leading up to partition? What, specifically, led to such violence and horror?

In my opinion, Muslims who had ruled the country for many centuries were sidelined during British rule. It was partly because the Hindu community was more educated and partly for political reasons. Muslims also could not forget they were rulers for so long, and had always regarded Hindus as an inferior community.

What have been the ripple effects of Partition from one generation to the next? How have you/do you pass on memories to children and grandchildren?

For many, it turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Many, though not all Sindhi Hindus, not only adapted to new situations and circumstances, but prospered quite beyond expectations. Necessity is the mother of invention. They faced the challenges with the utmost faith and courage. No Sindhi Hindu begged in the worst of circumstances.

How do the events of Partition continue to affect life throughout the subcontinent (India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) today? In retrospect, are you convinced that Partition was ultimately for the best?

I am not sure, but do not regret it personally. I also understand that those Sindhi Hindus who did not migrate for any reason have been living rather tensely and with fear of violence and conversion. Most Sindhi Hindus though have prospered as they have faced the new challenges with courage and determination.

What lessons should we take from that period?

Migrations and persecutions are the facts of human history. They obviously aren’t good occurrences, but sadly this kind of human weakness shows up throughout history time and time again, with many instances where sons have even fought and subdued their fathers in pursuit of a throne. Muslim history, unfortunately, is especially riddled with such problems.

Do you think Hindu-Muslim relations could ever heal to how they were before the 20th century? If so, what will it take?

Though I’m not so sure about Sindhi Hindus still living in Pakistan, I would say yes, I am always hopeful. I’ve actually heard that Hindu-Muslim relations in Malaysia are quite cordial. Full credit to their rulers and politicians, who I’m sure play a huge role in facilitating this.

What positivity, if any, came out of your people’s struggle?

As I said, necessity is the mother of invention. Most Sindhi Hindus are very spiritually inclined with the utmost faith, and thus very peace-loving people who tend to build a future through their own effort, not depending on any government doles or political help. As such, most, if not all, Sindhi Hindus have prospered since Partition, as some, of course, have become very wealthy in many parts of the world, including India, the US, the UK, Dubai and other places.

Have you had a chance to go back to your childhood or ancestral home? What would you like to see or do “back home,” if given the chance?

I really never longed seriously to go back, even for a visit, mainly because of the tense relations between India and Pakistan.

What is your hope for the future?

I am not so sure. As long as politically the two countries are not able to develop a friendly relationship, the overall scenario will remain unfavorable. But we must never lose our hope. We are all children of one God. Things can and should always improve.