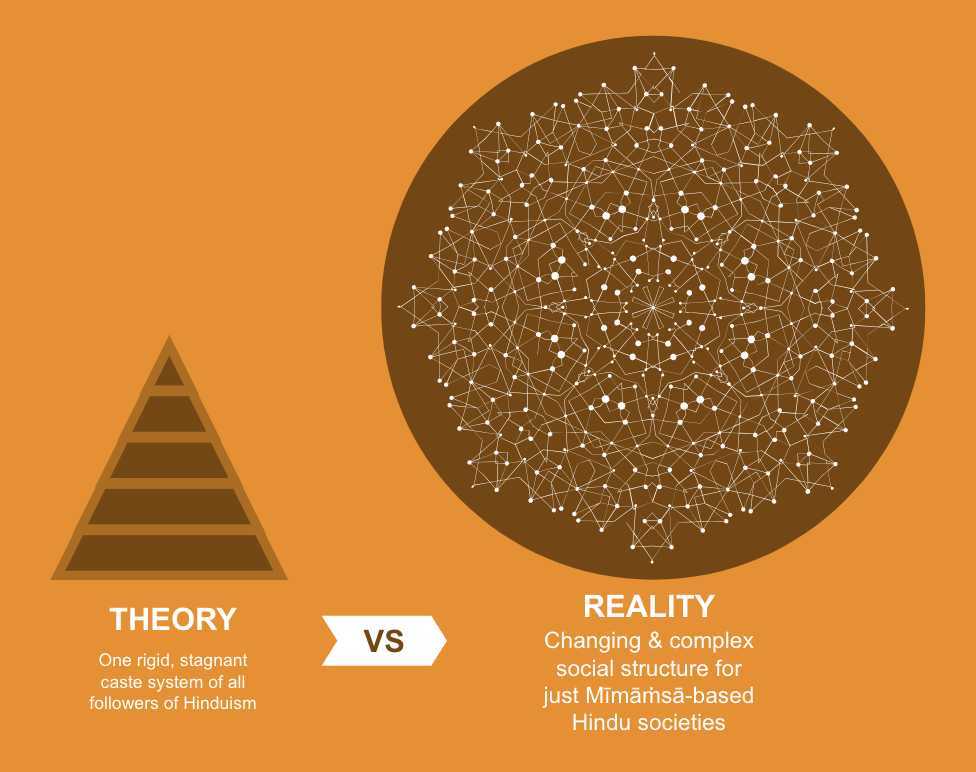

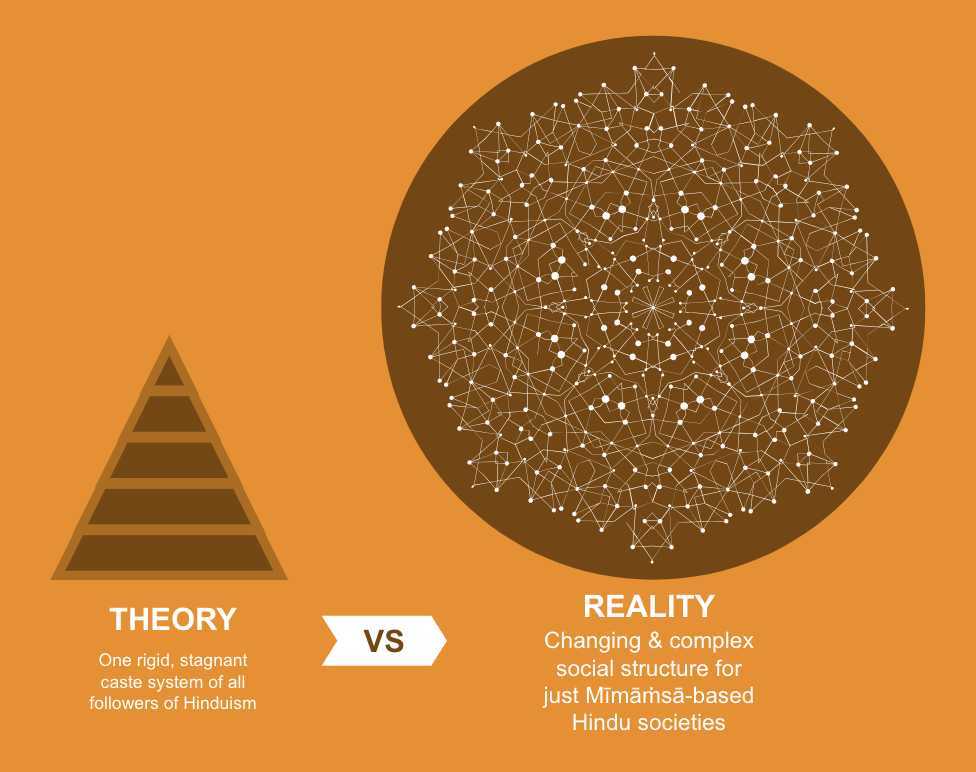

Caption: Two narratives, one history: On the left, the rigid hierarchical caste system, imposed by colonial narratives. On the right, the actual framework of ancient Indian history — diverse, fluid, and pluralistic in nature.

Growing up, history seemed pretty straightforward. All you had to do was open up a book and everything would be there: the people, the events, and most importantly, the narratives. The narratives, after all, were what gave form to the past, providing stark clarity on the cultures of before, and how their influence continues to shape the world around us today.

It wasn’t until I got older, naturally, that I realized the naivety of this thinking. That history isn’t just a black-and-white record of facts, but a reconstruction of the nuanced and complex, periodically expressed in facile depictions by those with biases. And while such depictions have their uses when done in good faith, it should go without saying that the simpler they appear, the likelier they are to be warped, oftentimes in tow with an agenda.

Needless to say, there are myriad cases one can point to, each connected to a specific people who take issue for obvious reasons. Muslims, for example, are framed as violent, Christians as anti-science, Jews as callously greedy. Considering, still, the push in recent years to have theirs enshrined into law, Hindus have felt a uniquely heightened sense of foreboding when it comes to the trope that has plagued them most.

I’m talking, of course, about caste.

In an effort to rationalize the subjugation of India, colonial Britain used the term to denigrate the country, painting its people as barbaric followers of an unchanging, oppressive, and hereditary social hierarchy. Now a singular focus of how Hindu culture is seen by the West, there are few in the public who know its falsity — a falsity that grows more false the more you look into it.

India, though homogeneously conveyed, is really made up of an eclectic spectrum of peoples going back to the ancient period, with roughly 4,400 tribes believed to have populated the subcontinent. While the earliest sources of the Indic historical record reveal little about their ways of life, details can be gleaned through the lens of the Aryas who, among them, left vast bodies of poetic compositions, datable to at least the second millennium BCE.

The Aryas, contrary to erroneous interpretations promulgated by colonialists, weren’t a race, but rather, a self-designated marker that denoted a particular culture. Despite Arya becoming the prevalent word for people as a collective, these people, therefore, were actually of numerous ethnicities and traditions, whose methods of organization can’t be generalized beyond even a single region.

This, however, doesn’t mean there were no common features among them.

A tapestry of pluralism

A svayam, or “individual,” was usually part of a parivara, or “multigenerational family.” A parivara was usually part of a kula, or “clan,” with shared ancestry and kinship, genetic or otherwise. Many parivaras and/or kulas, when sharing some kind of distinguishing social features, like teachings, customs, or language, etc., might form a jati, or “tribe.” And many kulas and/or jatis could ally through treaty or marriage and create a jana, or “tribal confederation,” usually with an elected leader and council.

The geographical territory of a jana was called a janapada, of which there were 64, along with three great Tamil dynasties, the Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas. Once janas grew and more governance was required, an elder of each family would form a samit, or “assembly,” and these assemblies selected a rajna, or “leader,” who had a sabha, or “group of small advisors,” consisting of purohitas, or “selected experts,” and senani, or “guards.”

When a group of janas allied through treaty or marriage, their combined territories were called a mahajanapada, or “tribal nation.” By 600 to 400 BCE, there were 16 mahajanapadas, each of them containing one or more urbanized areas that served as economic centers. As trade among societies increased, those that developed into nagaras, or “prosperous cities,” required further administration. This led to ganasanghas, or “oligarchic republics,” like that of the Vrjis and Mallas.

Occasionally, if based around an especially major city and trade network, several mahajanapadas would ally through treaty or marriage and form a samrajya, or “empire.” Non-totalitarian though in nature, such empires allowed clans, tribes, or their respective confederations to function in the forest or hills as independently as they desired. Those situated near or on trade routes or notable infrastructure, like ports, were afforded the same freedoms.

So lending itself to a broad, pluralistic framework of great variety within larger unified groups of people, Ancient India’s true societal ethos tells a very different story from that of an unyielding and tyrannical caste hierarchy.

Influenced, yet, as the world has been by ancient powers unable or uninterested in describing the diversity of people living beyond the river Sindhu, these people came to be known simply as “Indian” or “Hindu,” in tow with Greek and Persian mispronunciations of the waterway.

Thus caricatured as a monolithic culture, Hindus lost control of their narrative, which the British nefariously twisted into caste.

Fortunately, albeit difficult, narratives can change. May we all stay the course in the untwisting.