Up until the second half of the 20th century, Indian classical music was virtually unknown in the Western world. Even in India, the genre had only really started to gain popular traction during the first decade following independence.

From being jealously guarded by its masters, to being restricted to mostly dance halls and palaces, to being shunned by the educated middle class as frivolous, Hindustani music in particular was, for many years, narrowly embraced.

But this all changed in the early 1950s, when Yehudi Menuhin, one of the most celebrated American violinists of the 20th century, discovered Ravi Shankar and his brother-in-law Ali Akbar Khan during a trip to India.

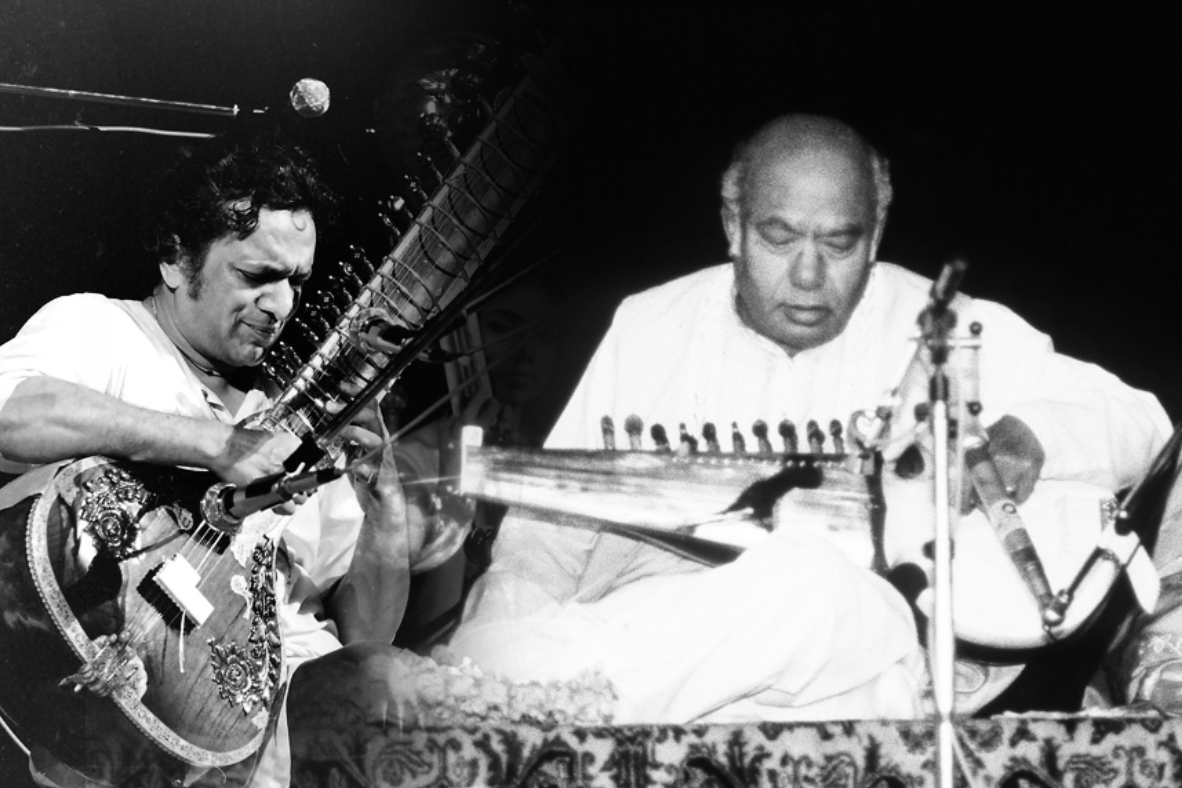

The first, a player of the sitar, and the second, of the sarod, the two were masters of their craft, displaying through their respective stringed instruments the full potency of North India’s musical heritage. Employing the use of ragas (the melodic framework for composition and improvisation of which there seemed an inexhaustible variety) against often complex rhythmic patterns known as talas, the exotic nature of the music took Yehudi Menuhin by surprise, who had known nothing of its power and richness.

Enchanted, Yehudi Menuhin invited Shankar — the more outwardly charismatic and affable of the two — to present a concert at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1955. Shankar, however, declined, so Khan reluctantly made the trip instead.

Touted by Menuhin as “the greatest musician in the world”, Khan’s mastery and experience overshadowed his grudging disposition, as he and the audience showed a mutual appreciation for each other. A landmark trip, Khan became the first practitioner of Indian classical music to perform in America, the first to release an album of Indian classical music on an American label, and the first Indian musician to play on an American TV show.

In many ways, you could say that he was more than prepared for these opportunities. Born into a legendary lineage of royal court musicians whose service traces back to at least the 16th century, Khan began studying music at the age of 3 under the tutelage of his father, Allauddin Khan.

Considered the greatest personality in North Indian music of the 20th century, Khan’s father was a towering figure, teaching his son under a rigorous system that often included 18-hour practice days. Decades of such practice made playing the sarod as natural as speaking for Khan, who made his first public appearance at 13 and his first recordings in his early 20s. It was in his 20s that he also became a court musician for the Maharaja of Jodhpur, holding the post for seven years and earning the title Ustad, a Persian word meaning “master musician.”

In spite of such mastery, however, Khan did not find fulfillment in showmanship. Though he would tour extensively throughout his life and even end up with more than 95 albums to his credit, like his father, he yearned to teach, and was unfazed by whatever taste of fame he experienced during his trip to America. He thus returned to India, where he opened the Ali Akbar College of Music in Calcutta.

Nevertheless, his stint in America was an important one. Like a key, he had unlocked the door to America’s psyche, leaving it open for the right person to walk in and sow deeper connections that would prove invaluable in disseminating Indian classical music throughout the West.

This person, of course, was Shankar. Though he missed the trip in 1955, he toured America in 1956. Having also trained under Khan’s father, he too was more than prepared technically. Unlike Khan, however, Shankar was prepared in other ways as well.

At just 10, he went to Paris and joined his older brother’s Indian dance troupe, becoming, within five years, one of the company’s star soloists, as they did tours of not only Europe but America as well. Hence, embodying a natural charisma, an ability to relate to audiences, and an instinct for experimentation, Shankar was just the ambassador Indian classical music needed.

At first, his concerts in America attracted a jazz following, who could relate to the improvisational nature of his music. Richard Bock, founder of World Pacific Records (originally called Pacific Jazz Records), soon took notice, and began recording Shankar, as his label went on to produce most of the albums Shankar made in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Through Bock, Shankar’s influence expanded, as he met and performed with jazz legends Bud Shank and Paul Horn, befriended John and Alice Coltrane, and collaborated with renowned composer Philip Glass.

But of course it was when he met George Harrison that Shankar and Indian classical music truly saw a thunderous rise in popularity. David Crosby, whose band The Byrds was also recording for the World Pacific label, became aware of Shankar through Bock, and subsequently turned his Beatle friend on to the sitar master.

The two met at a pivotal time in George’s life. By the age of 22, the Beatle had reached the pinnacle of material success, only to become disenchanted by its transitory nature. Looking for something more, he began taking sitar lessons from Shankar, who showed him that music could be a gateway to experiences beyond such transitoriness.

A spiritual mentor and father to the guitarist, the evolution of their relationship, along with Shankar’s American success, became emblemized by the Concert for Bangladesh. Hoping to raise money and awareness for the victims of Bangladesh’s 1971 genocide, Shankar asked George for help, who proceeded to organize the charity concert.

Involving a slew of performances by some of rock’s greatest artists, the concert also comprised an Indian classical music section, which was led by Shankar, and included none other than Khan on the Sarod.

Playing an afternoon and evening set to over 40,000 people, the event was a resounding success. Yet, even as the concert raised millions of dollars, both Shankar and Khan couldn’t help but feel a little wary of the rock and roll audience that attended

They appreciated the growing interest young Americans showed in their music. Such interest had even increased their Indian audiences as the genre became a subject of national pride. Still, they disliked playing to crowds in which people were taking drugs, drinking alcohol, and making out while listening.

More than anything, Indian classical music was supposed to be a sacred experience, a deep meditation in which listeners could “feel the sweet pain of trying to reach out to the Supreme,” as Shankar put it. He had done and would continue to do immense work in exposing Hindustani music to the masses. It had become clear, however, that just as much work would need to be done to preserve the intention and integrity of the tradition that came with it.

And none was better for the job than Khan, who indeed fulfilled such a task. Though he had opened his college upon returning to India, it closed in the ‘60s, after which he went back to America where he started the Ali Akbar College of Music in California.

Understanding that his students couldn’t practice 18 hours a day, the same way he had, Khan committed himself to passing on the purity of the tradition. This meant placing special emphasis on cultivating the respect and devotion required to play the music with a spiritual sincerity that could uplift both the musician and the audience.

Teaching an estimated 10,000 American students throughout his life, one of which went on to open a European branch of the college in Switzerland, Khan also worked to establish a library and archive of Indian classical music. Containing more than 40 years of his compositions, recorded classes and performances, as well as articles, reviews, historical photos, and books, Khan went to great lengths to preserve and democratize North Indian classical music in an unprecedented way.

Thus, while Shankar exposed Indian music to the masses, Khan taught it to the masses, as the two succeeded in transplanting a once relatively obscure, yet deep tradition onto American soil, where it has continued to grow and blossom over the decades.

Ravi Shankar photo: Markgoff2972

Ali Akbar Khan photo: Alephalpha