It didn’t take long for England’s missionaries to come to a conclusion about India upon completing their earliest visits to the region. It was, in their eyes, an uncivilized country, filled with the most barbarous habits of mythology, polytheism, and perhaps worst of all, idolatry.

To them, scenes of worshipers bowing down to ghastly statues of some strange god or goddess was enough to be considered a truly grotesque example of human degeneration. When they realized, however, such worship extended to that of animals, rivers, trees, and even objects like stones, they were certain the people of India were deluged in a frightful culture of ignorance, one that was, to be sure, immeasurably beneath their own Christian background.

It was thus with this attitude they invaded India, plundering the country for its abundance of gold, jewels, and other natural resources, eventually endeavoring to root out the culture of its primitive inhabitants, who were lucky to be bestowed with a new and infinitely more civilized one.

The world’s perception of India has evolved significantly since those days of British colonialism and the missionary fervor of the 19th century. Though many people now have recognized the immense value Hinduism’s traditions contain — most popularly yoga and most recently through Ayurveda — a lack of appreciation for many of its other practices, fueled by a lack of understanding, continue to persist. This, of course, is incredibly unfortunate, considering these practices have much to offer in terms of addressing some of the major issues plaguing our time.

When it comes, in particular, to the issue many consider to be the most pressing — the ongoing ecological crisis threatening us all — it just so happens the practice the British found most egregious, anthropomorphism, or the act of placing human traits on non-human aspects, imbibes the very mood we need more of to restore the health of the environment.

A lofty claim, to be sure, this mood, fogged to outsiders by a false perception of its primitiveness, can indeed save the planet, if we can only begin to understand the foundation from which it is built upon: a fundamental worldview that everything around us is sacred.

Perhaps a somewhat nebulous concept on the surface, sacredness, from a Hindu perspective, stems from the idea that all of creation originates from the same Divine source, and so everyone and everything, including animals, nature, and even inanimate objects, are permeated by its presence.

The more connected we become to this presence, the more connected we become to all that surrounds us, as natural feelings of this connectedness, like appreciation, gratitude, honor, and empathy, foster within us the desire to take care of the delicate balance that maintains all of existence.

But how do we become more connected, especially when such connectedness does not arise as seamlessly in some of us as it does so in others?

The answer, unequivocally, is love. The greatest connections we have in this world are fastened by the knots of love, and those knots are fastened most tightly, of course, not to things, but to people.

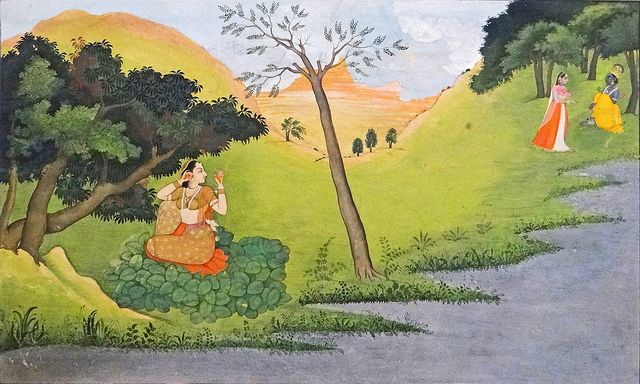

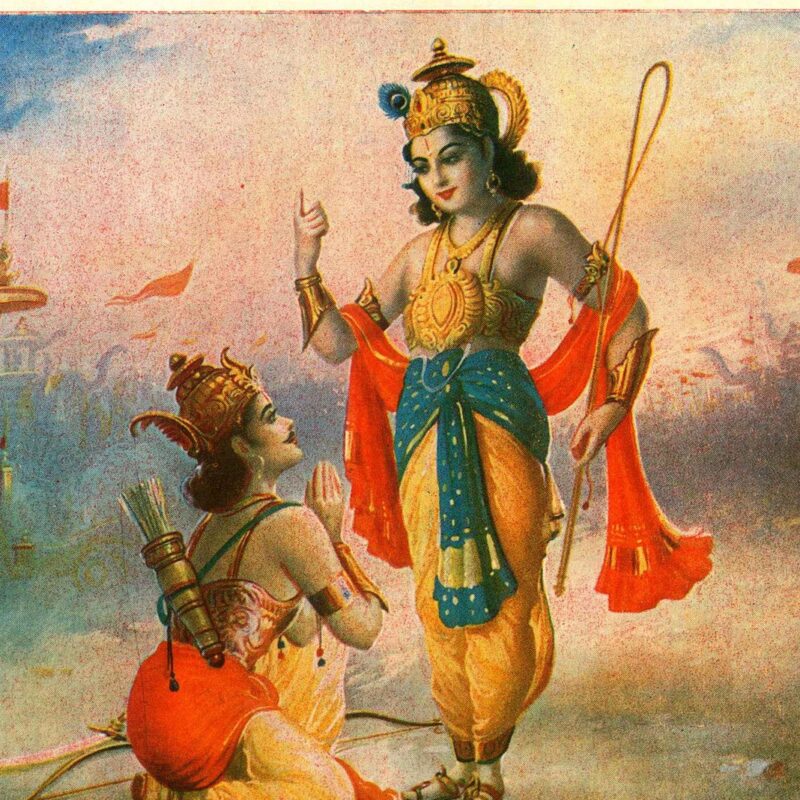

Divinity, therefore, along with being unlimited and all pervading, exists in a countless multitude of personal deities with whom devotees can cultivate loving relationships. As devotees develop these relationships, it’s only natural they also develop the desire to look after the physical forms in which those deities manifest on earth, be it a river, a tree, a mountain, etc.

Thus seeing the world’s natural phenomena in connection with gods and goddesses who need to be lovingly taken care of, anthropomorphic communities have built within them an innate and powerful potential to look after nature the way it needs to be, especially compared to the model used by the world’s Abrahamic traditions, namely anthropocentrism.

Placing human beings at the center of reality, anthropocentrism gives man, who is said to have been created in the image of god, dominion over nature which, seen as purely mechanistic and devoid of spirit, holds no meaning beyond the usefulness it provides through its resources. The earth’s oceans, lakes, rivers, and forests still have to be managed from this view point, but only because they’re needed for human survival, and nothing more.

Now there are many who would say, “What’s the big deal? As long as the resources are managed, why does it matter what the motivating factor is?”

The issue is that without the loving impetus, man’s relationship to nature becomes simply that of manipulator and manipulated. As man’s powers of manipulation grow more sophisticated through the advancement of technology, the corrupting nature of this power can lead to the degradation of proper environmental maintenance, particularly when such maintenance gets in the way of the bottom line — an unfortunate and obvious reality of modern Western culture.

Of course, when one looks at America, a country at the pinnacle of modernity, and sees that a myriad of its natural resources, particularly its rivers, are generally cleaner than India’s, which are notorious filthy, the claim that anthropocentrism is worse for the environment could seem like a laughable notion.

The truth is, however, that in tow with the advancement of industrialization, America’s rivers were once on a horrifying path of degeneration. It wasn’t until 1969, when Time Magazine published dramatic photos of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River after sparks from a passing train set ablaze the oil-soaked debris floating on its surface, that the state of America’s waters became a topic of national concern.

The river, described in the article as being so saturated with sewage and industrial waste it oozed rather than flowed, was just one of many that had caught fire during that period. The incident, in fact, was at least the 13th time an Ohio waterway had been set ablaze, a number that was but a portion of the overall tally of river fires occurring in the country’s most industrialized cities.

Hence shedding light on the obvious pervasiveness of the issue, the Time Magazine article sparked a number of wide-ranging reforms, including the passage of the Clean Water Act, which helped to establish a basic structure for regulating pollutant discharges into America’s waters.

Though the implementation of these reforms have done a great deal in terms of cleaning the country’s rivers, they have been like band-aids in terms of the impact the exponential growth of technology has had on the environment since the ‘60s.

Based on the state of the climate, it’s clear the anthropocentric model, a model in which we exploit the world’s resources and address the negative environmental consequences of such exploitation only when we become directly affected and not otherwise, isn’t working for America.

It also, for that matter, isn’t working for any other country, like India, whose rivers are polluted not because of its people’s “primitive” anthropomorphic practices, but because they have strayed away from these practices, going all in on the model that made Western societies so materially wealthy.

Categorized as a newly industrialized nation with the planet’s fastest growing economy, India, according to data compiled in the 2021 World Air Quality Report, now contains 21 of the world’s 30 cities with the worst levels of air pollution.

This, in many people’s eyes, as it would be in the eyes of those who first colonized India, is supposedly a sign the country is becoming a more advanced nation, but nothing could be further from the truth.

If we actually want to save the world by restoring the health of the environment, it’s high time we redefine what an advanced culture is actually supposed to look like.

Is it one in which humans, charged with their own self-importance, manipulate the environment solely for the pursuit of pleasure? Or is it one in which humans, seeing all of existence as sacred, live in harmony with nature, not out of self-interest, but out of gratitude and love for what it provides to all of us?

If you enjoyed this piece, then you may also be interested in reading “If India’s rivers are so revered, why are they so polluted and what are Hindus doing about it?”