From a broad statistical standpoint, Hinduism’s roughly 0.2% presence in Africa is seen as so inconsequential, most data organizations don’t even bother explicitly mentioning it in their census reports. Instead, they opt to clump the religion, along with a medley of the continent’s other minority faiths, into a 1% usually categorized as “others” and simply leave it at that.

Broad statistics, however, can sometimes be deceiving, especially when it comes to figures so large even minuscule percentages are significant in terms of actual numbers. Such is the case regarding Africa’s Hindu adherents whose 0.2%, in the context of the continent’s 1.2 billion population, ends up being an estimated 2.5 million.

As such, Hinduism, though sparsely practiced throughout the continent in comparison to religions like Islam and Christianity, can be found in notable pockets, pockets in which the culture, despite seeming out of place, is expressed just as beautifully as anywhere else in the world.

While the scattered nature of these pockets can make understanding Africa’s Hindu story a somewhat complex endeavor, a handful of the most noteworthy of these pockets can still give an overarching view of what this story entails. With the hope of providing said view, here are four of the countries where Hinduism’s presence is particularly worth mentioning, and why.

1) South Africa

Before the Union of South Africa (the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa) was founded in 1910, the area was made up of four separate British colonies: Cape, Transvaal, Orange River, and Natal.

It was in this last colony, Natal, now part of the KwaZulu-Natal province, that Hinduism really began taking root in the African mainland. The government, needing a cheap replacement for the labor plantation owners lost after slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire, decided to do what several other colonies had already begun doing: import Indian nationals under a system of indentured servitude.

Presented with the opportunity of new beginnings — specifically five-year contracts, after which they could sign on for another five years, followed by the opportunity to settle permanently with crown land and full citizenship rights — 6,445 impoverished yet hopeful Indians journeyed to Natal between 1860 and 1866.

Sadly, these early immigrants were treated more like slaves than hired workers, brought on overcrowded ships, housed in military-style barracks, and forced to work under terrible conditions. So bad was the ill-treatment of laborers, in fact, that immigration was paused after 1866.

In 1874, however, it resumed in full throttle, as thousands of new immigrants poured into Natal, and not just indentured laborers, but also a community of traders, artisans, and teachers, who made the trip at their own expense. Over time, many laborers who completed 10 years of service, equipped with the skills they acquired during their indentureship, joined this community, which quickly began expanding.

Concerned by the possibility that Natal could become majority Indian if this growth remained steady, in 1891, the government decided to revoke the promise it made regarding the gifting of land and citizenship.

Regardless of this move, Indians made up almost half of Natal’s population by 1893, and by 1904 they actually outnumbered the whites. By 1911, after all of the colonies joined to become the Union of South Africa, thereby putting an end to Natal’s indentureship program, the colony had been the recipient of more than 150,000 Indian immigrants.

As South Africa became more industrialized, the decades that followed saw the rapid urbanization of Hindus who began moving into the cities, most notably Durban, the Indian population of which increased from 17,015 in 1911, to 123,165 in 1949.

Though, during this period, this population faced a myriad of challenges, including high levels of unemployment, wide-scale poverty, and various efforts by the government to have them repatriated, they persevered, building temples and schools so their youth could become better educated in Hindu culture, as well as have access to better jobs.

Therefore establishing themselves firmly in the cultural fabric of the city, Durban is now home to most of South Africa’s 1.3 million Indians, making it, according to some sources, the largest Indian city outside of India, and thus a most powerful hub of Hindu practice.

2) Mauritius

While Natal was the first British colony in the mainland to become part of the Indian-indentured-servant program, it was actually Mauritius, the island located roughly 1,200 miles off the southeastern coast, that was the first British colony in Africa (in all of the empire, in fact) to start importing Indian workers in the new post-slavery system.

Having once been the recipient of Indian workers under French colonial rule, 6,000 of Mauritius’ 80,000 population was already Indian when Britain began its indentured program, thus making it a more appealing work destination for recruits — some of whom had relatives there — even after other colonies began competing for their services.

Because of this, Mauritius’ Indian population swiftly grew, despite Parliament having to pause the program for two years due to the ill treatment of workers like it later had to in South Africa, as 700,000 laborers migrated to the island between 1834 and 1920.

Today, 50% of Mauritius’ 1.3 million population is Hindu, making it the only African country in which Hinduism is the religion with the highest number of followers.

The island, as a result, is sometimes referred to as “little India,” where almost all of its presidents and prime ministers have been Hindus, and where most Hindu celebrations are public holidays.

3) Uganda

Generally speaking, the story of Hinduism in Uganda begins in somewhat similar fashion to that of South Africa and Mauritius, or any other British colony for that matter.

Requiring cheap labor, this time for the construction of the Uganda Railway that would connect Kampala in Uganda to Mombasa in Kenya, the British imported around 40,000 Indian workers in the 1890s.

After completing the project in 1902, a majority of the laborers returned to India, while a small percentage opted to stay and continue work in railway and other British operations, like retail and administration.

Comprising just a sliver of Uganda’s overall population, this small percentage was soon joined by a wave of new immigrants — mostly traders — who began establishing their own businesses. As these businesses prospered, spurring even more immigrants to come and work, the Indian population became instrumental in developing the country’s economy through and beyond the end of colonialism.

Unfortunately, the period after colonialism was also one in which discrimination against Indians rose to particularly high levels, as part of the policies of various East African governments who felt that indigenous Africans should be at the forefront of the economy.

Such xenophobic policies reached their culmination in 1972, when military dictator General Idi Amin announced that all of the Indian-origin people living in Uganda — numbering, by that time, almost 80,000 — had to leave the country. If, after 90 days, any of them were still there, they would, as he put it, be made to feel as if they were “sitting on fire!”

Hence leaving their businesses and homes to be seized by the government, all of the region’s Indians mass migrated to a medley of other countries, including around 28,000 to the United Kingdom, around 15,000 to India, and around 8,000 to Canada.

Thereafter faced with a shortage of skilled professionals, the expulsion of Indians actually caused Uganda to fall into a financial crisis, resulting in long-term economic devastation.

20 years after the exodus, Uganda reversed its laws banning Indians, offering to give back their seized properties with hopes they would return and reinvigorate the economy by recreating employment. Having already rebuilt their lives in other parts of the world, however, a majority who left Uganda in ‘72 decided to simply sell their reclaimed property and not move back.

There was, on the other hand, a minority who indeed returned, with some even repossessing the businesses they originally owned. Now numbering 30,000, Ugandan Indians once again hold controlling stakes in various sectors of the economy, employing more than 1 million indigenous people, and contributing to more than 65% of the country’s domestic revenue.

4) Ghana

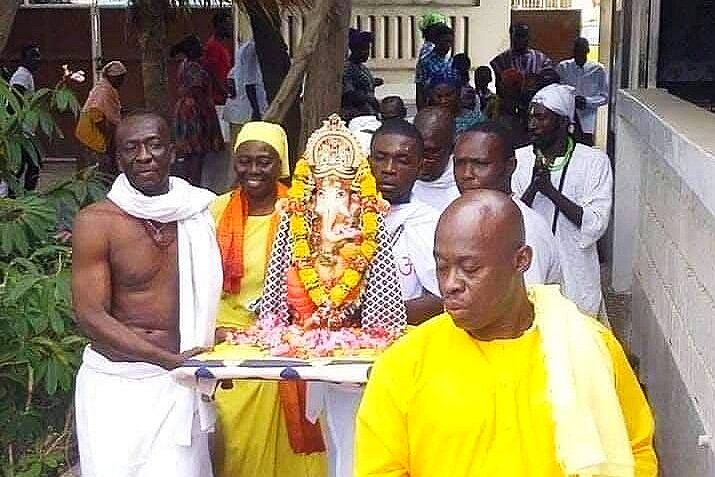

Ghana’s Hindu community, from a broad perspective, is made up of two distinct groups: Indians and indigenous Africans, both of whom get along very well, regularly sharing spaces of worship and occasionally banning together to host visiting teachers or dignitaries.

During the first half of the 20th century, the Indian community was very small, consisting mostly of Gujaratis who settled in the country in the colonial era — not as indentured servants, but as merchants seeking economic opportunities. After 1947, however, this group was joined by an influx of Sindhis who migrated to Africa, spurred on by the partition of India, thus adding to Ghana’s overall Indian population.

Because, for the most part, this population engaged in their cultural practices privately due to the general assumption Hinduism was an Indian faith that might be unappreciated by foreigners, the migrants made no real attempts to introduce their traditions to the native Ghanaians during this period. The religion, as a result, remained only among the Indians for a long time.

The Ghanaians, nevertheless, still managed to have encounters with Hinduism throughout this period. Soldiers who had served alongside the British in Sri Lanka and India during World War II, according to reports, came back to Ghana with remarkable tales of Hindu gods and mysticism, arousing in the Africans a curiosity for India and its spiritual culture.

Fueled not only by the popular rise of Hindi movies, which were characterized by supernatural displays of spiritualism, but also by the appearance of various astrologers and healers who claimed connections to Hinduism, this curiosity rose throughout the decades.

When, in the 1970s, a new wave of Hindu groups thus began arriving in the country — ones whose goals were to actively share their traditions with the indigenous — many of Ghana’s people were primed to reciprocate, despite the hostile public reaction instigated by Christians.

As such, Hinduism began taking hold among Ghana’s native, so much so that the indigenous Hindu community now actually outnumbers the Indian community, and Hinduism as a whole is the country’s fastest growing religion.

If you enjoyed this piece, then you may also be interested in reading “What it’s like to grow up African American and Hindu”