There are several beliefs on how Bangladesh’s capital city, Dhaka, acquired its name.

Some theorize it to be derived from the Sanskrit dhakkya, meaning “watchtower,” as the region was most likely used as a post of observation to help protect Bengal’s earlier strongholds, Bikrampur and Sonargaon, which were situated nearby.

Others say it was possibly named after the country’s traditional dhak drum, which was used as a tool of measuring the city’s boundaries by marking the distance at which its sound could no longer be heard. And still others say it came from the butea monosperma, a species of tree native to the area, commonly referred to as the dhak plant.

But, considering Bangladesh today is roughly 90 percent Muslim, probably the most interesting theory regarding its capital’s name, and perhaps the most popular, centers around the city’s most important historical Hindu monument: the Dakheshwari Temple.

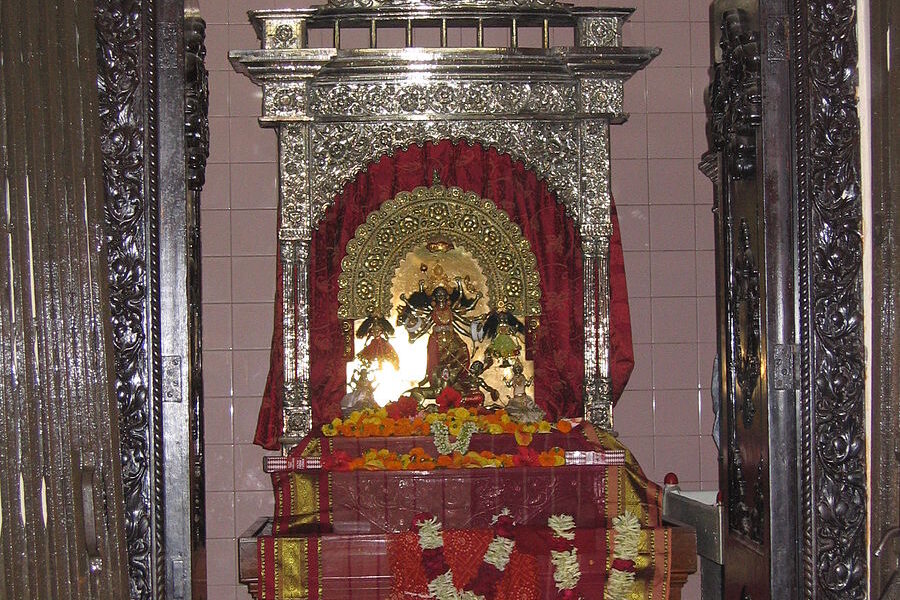

According to legend, it was founded sometime in the 12th century CE by a Hindu king named Ballal Sen, who was inspired to build the temple after finding a statue of the Goddess Durga buried in a particular part of the jungle, exactly as revealed to him in a dream.

Upon finishing construction, he installed the deity, calling her Dhakeshwari, or “the concealed Goddess,” as the temple was established in the thick Bengal jungle, and thus covered (dhaka in Bengali) by the forest veil.

Unfortunately, the passage of time, which brought with it numerous renovations, repairs, and rebuildings, has made it impossible to determine whether initial erection was actually at the purported time of this story.

Because of this, the temple, as it exists today, is considerably more recent.

In his 1912 Eastern Bengal District Gazetteers: Dacca, which traces the background of Eastern Bengal’s “Dacca district,” Basil Copleston Allen wrote that the present temple, according to tradition, is said to have been erected in the early 1700s by an employee of the East India Trading Company.

This, however, does not in any way diminish its historical influence and significance as Allen also included an 1867 account of the temple, which stated that it was, in olden times, “a most famous place of resort,” and that every stranger who visited Dhaka was “expected to lose no time in presenting himself before the Goddess with an appropriate offering…”

Indeed, the glory of the temple was immense, and all the more highlighted by the fact that it was, and still is, considered by many to be a shakti pitha — one of the significant shrines and pilgrimage destinations in the Goddess-focused Hindu tradition known as Shaktism.

Sadly, such glory has not made it immune to Bangladesh’s tumultuous past, especially in the last century or so, beginning with the communal clashes that were increasingly taking place in Bengal after Partition in 1947.

Scared that the vandalization and desecration they saw occurring at various Hindu sites throughout the region during that time would soon reach Dhakeshwari, a group of the temple’s leaders decided to have Durga moved.

Thus, in 1948, the idol was tucked into a box and, further protected by a layer of clothes and newspaper, packed into a suitcase and carried to Kolkata. There, in the Kumartuli area, she was eventually reinstalled in a newly constructed temple where she continues to reside today.

A new Durga was later installed in the Dhaka temple, and unlike the original deity, which has eight of her 10 hands empty, the new one has all of her hands occupied, carrying many more weapons, as if to signify the site’s turbulent legacy.

This turbulence was especially bad in the 1960s, marked by increasingly repressive government policies, including the Enemy Property Act (now called the Vested Property Act), which led to a large portion of the temple’s property being unjustly confiscated.

These policies, of course, were merely a precursor to Bangladesh’s darkest period, the 1971 Bangladeshi Hindu genocide, considered one of the worst genocides in modern history.

In its onslaught of thefts, rapes, killings, and destruction of properties against Bangladeshi Hindus, Pakistan destroyed over half of the Dhakeshwari Temple’s buildings, as its soldiers took over the main worship hall to be used as an ammunition storage area.

The temple underwent massive renovations after Bangladesh successfully gained its independence, but was the subject of violence once again when, in the early 1990s, it saw repeated attacks by Muslim mobs who were incensed after the destruction of the Babri Masjid in India.

Determined to protect and preserve Dhakeshwari going into the future, Bangladeshi Hindu groups launched a major campaign to establish the site as the focal point of Hindu culture and worship in the country. In 1996 this met with resounding success, when the temple became officially recognized as the jatiya mandir, or “national temple” of Bangladesh.

No longer hidden by the thick jungle canopy, which has long since been cleared away, the temple is now situated in the heart of bustling Dhaka, hosting some of the largest Hindu festivals that take place outside of India.

Janmashtami, or Krishna’s birthday, for example, is one of the most important events of the year, known especially for its vibrant and colorful procession. Starting from the temple itself, the parade leaves the premises, flooding the capital’s streets with throngs of devotees who, in a spiritually infectious display of singing and dancing, induce many of the street-side onlookers to sing and dance along with them.

Eventually returning to the temple with a triumphant finish, the procession is emblematic of Janmashtami’s significance in Bangladesh, where it is honored as a public holiday.

Yet, if first-time visitors really want to experience Bangladeshi Hinduism in its full glory, they should go to the Dhakeshwari Temple during Durga Puja — unequivocally the country’s largest and most important Hindu festival.

A five-day celebration culminating in processions of its own, the holiday pulls several thousand devotees and onlookers, as well as a stream of the country’s top dignitaries and leaders, including Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina who, in 2018, gifted land to the temple authorities to help make up for what was lost due to the Vested Property Act.

Also attracting some of Dhaka’s top performers in the music and film industry, the holiday is an undeniable indicator that the temple is more than just a religious destination: it’s a remarkable socio-cultural hub without which the city would and could not be the same.

As such, whether the capital is, in fact, named after the temple doesn’t really matter, for in the eyes of Hindus, Dhakeshwari has, and always will be, the Goddess of the city.