The act of walking around someone or something has been a fundamental part of Hindu pilgrimage traditions since time immemorial.

Known as parikrama, literally “the surrounding path,” this type of circumambulation is a way of showing honor to a form of sacred significance, in tow with a person’s devotional disposition. While for many, this might be the obvious teacher, temple, or deity connected to a particular spiritual discipline, there are many others, perceiving divinity’s expression in a wide range of manifestations, who endeavor so far as to encircle lakes, rivers, trees, and hills — or even whole cities for that matter.

It should thus come as no surprise that among the especially determined and dedicated, one of Hinduism’s most popular parikrama paths isn’t limited to a single site. It takes the intrepid devotee around all of India, in a pilgrimage tour called Char Dham.

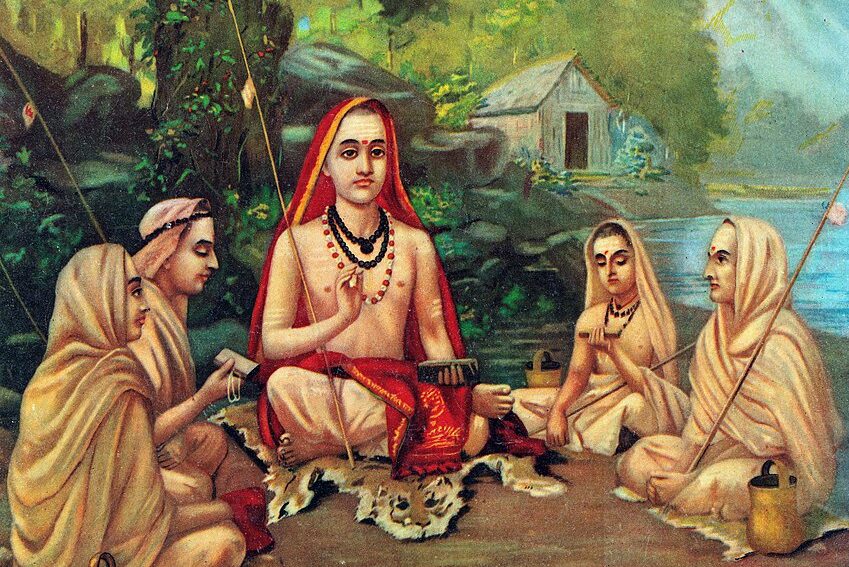

Char Dham, as is generally understood, finds its origin with the ninth-century mystic and scholar Shankara, who was Hinduism’s greatest exponent of Advaita Vedanta philosophy, a non-dual school of thought where the atman, or the individual divine self, and Brahman, or the Divine, are seen as one and the same, with no separation between them.

In his arrangements to ensure the wisdom of the tradition be preserved after his passing, it’s believed he asked his disciples to establish a monastic center in each of the land’s four directions. Though, naturally, much of this narrative is mired in obscurity, what’s clear is the power of the legend was such that pilgrims came to mold the image of India’s landscape with respect to four temples, which indeed stand at the major compass points of the country.

Anchoring the network of Shankara’s orders of renunciants to this day, these temples are revered by seekers as immensely auspicious dhamas, or “divine abodes,” imbued with the ability to bestow upon devotees unique and powerful spiritual benedictions.

1) Badrinatha

Up in the Himalayas, more than 10,000 feet above sea level, on the banks of the Alakananda River, the northernmost of the four dhams can be found, containing at its heart, the shrine of Badrinatha, dedicated to Vishnu (the god of preservation).

Dwelling in a squat structure that has a small cupola vibrantly painted in shades of blue, red, orange, and gold, the deity — a shalagram, or sacred stone image — resides in a state of meditation, seated naturally in padmasana, the yogic lotus pose.

This form of the Divine, named Badri Narayana, who along with his brotherly companion and devotee, Nara, performed austerities in the mountainous area for the ultimate benefit of mankind, is said to have been honored there for thousands of years until, in Buddhist times, his murti or deity was cast into the river.

His worship, eventually reestablished by Shankara himself, who purportedly retrieved him from the waters during a visit to the region, is now the primary draw for pilgrims, though not the only.

Famous as having been a retreat for some of Hinduism’s most revered ascetics and yogis, who also traveled there for the darshan (auspicious glimpse) of Narayana, the landscape is littered with sacred rocks, rivers, lakes, and hills, connected to Vishnu and his luminous devotees, making Badrinatha’s grounds the perfect place for one to follow in their footsteps.

2) Puri

Along the coast of the Bay of Bengal, on a hill called Nilachala, one of India’s largest temples sits as one of its most prestigious religious destinations, and hence the focal point of the easternmost of the four dhams.

Covering some 400,000 square feet, with immense facilities that produce food for roughly 20,000 people on a daily basis, the grand and munificent nature of the complex’s structure and activities is a reflection of its main deities, Jagannatha, Baladeva, and Subhadra, who reside in the premises’ inner sanctum under a shikhara (spire-like formation) stretching 200 feet high.

Black in complexion, with a wide euphoric smile, large beaming eyes, and little stumps for arms, the blockish image of Jagannatha is said to be an especially magnanimous form of Krishna, whose disfigurement is a divine physical reaction he undergoes when deluged in particularly intense feelings of love and appreciation for his devotees.

It’s such love and appreciation that fuels the festival Puri is most known for, ratha yatra, during which Jagannatha — along with his brother Baladeva (colored white) and his sister Subhadra (colored yellow), who share both his feelings of love as well as the resulting physique — is taken out of the temple for all of the public to see.

Placed on huge wooden carts, they are then pushed and pulled by devotees — numbering more than a million — who bask in the deities’ euphoric compassion, the power of which saturates the land with an extraordinary kind of spiritual potency.

3) Rameshvara

At the distant end of India, opposite the northern slopes of Badrinatha, the temple compounds of Rameshvara, the southernmost dham, occupies Pamban, the offshore island that extends from the coast of Tamil Nadu toward Sri Lanka.

Sometimes called Setu, or “bridge,” it was here that Prince Rama, according to various texts, built a bridge to Lanka — with the help of an army of vanaras (intelligent forest dwellers) — where his wife Sita was being held captive by the power-hungry king Ravana.

Several accounts say that upon returning to Rameshvara with his entourage after successfully rescuing Sita, Rama, hoping to cleanse himself of the karmic debt generally attached to the kind of violence he caused in slaying Ravana, decided to perform a worship of Shiva, who he was a great devotee of.

Needing a sacred stone by which he could establish a linga, the primary murti, or devotional image dedicated to Shiva (the god of transformation) Rama asked Hanuman, the strongest of the vanaras, with unfathomable supernatural abilities, to procure one from Mount Kailasa, Shiva’s famed abode in the Himalayas.

But as the astrologically determined time to install the linga arrived, and Hanuman had yet to come back, Sita, for the inaugural purposes, assiduously fashioned a temporary one of sand, which was to be replaced after the impending arrival of the Himalayan one. When, however, Hanuman did finally return, and nothing, including even the full strength of his own might, could budge the sand linga, which somehow turned inexplicably immovable, both ultimately remained in the area, becoming the main attraction of the Rameshvara Temple.

Still a remarkably divine oasis, pilgrims from all over the world can be seen walking down the site’s numerous circumambulatory corridors with a bucket, drawing water from each of its 22 tirthas (sacred wells) before entering the sanctum with their collected offerings to Shiva.

Though all arrive with various forms of karmic baggage weighing on them as Rama’s weighed on him, it’s clear they also leave the way he did: spiritually cleansed, recharged, and invigorated.

4) Dvarka

On the far point of Saurashtra (the peninsular region of Gujarat), the westernmost site of Char Dham’s grand and illustrious pilgrimage tour ascends from the edge of the ocean, brandishing a huge golden flag that flies atop its towering shikhara.

Inside its main shrine, a jet-black, four-armed image of Krishna is installed as the temple’s central focus. Standing in contrast to the sweet and playful cowherd form exhibited in his boyhood pastimes, the demeanor of this deity is that of a majestic monarch, indicating a more royal Krishna, who is believed to have ruled in his adult years as leader of the ancient kingdom of Dvarka.

Going back roughly 5,000 years to the purported period of the Mahabharata (the world’s longest epic), Krishna, who appeared as a Divine protector of dharma during a time the world was under terrible threat from the forces of disorder, relocated his capital to the region, which he knew would be better fortified, flanked by the protective vastness of the sea.

Employing Vishvakarma, the “Architect of the Gods,” to design the construction, Dvarka was built with the finest of materials, boasting lush greenery, dazzling palaces, and elaborate street systems, making it a truly magnificent abode rivaling even that of the heavens.

Renowned as it was, the day Krishna disappeared from the world, hence concluding his earthly pastimes and mission, the ocean, according to accounts, rose and submerged the city, as it became but a memory in a matter of moments.

Eliciting immense interest over the centuries, several major marine archaeological expeditions exploring the coast around Dvarka have been mounted, which indeed led to the discovery of what appear to be city remains lying beneath the waters, including remnants of buildings, streets, ramparts, and materials suggesting an ancient port.

Captivating as such findings are, whether they actually prove the historicity of Krishna and his kingdom — the subject, of course, has been one of hot dispute — is really only marginally pertinent to the faithful who travel from far and wide to visit the city as it exists today.

A thriving pilgrimage destination, the temple and its deity are not just a window to a possible legendary past, it’s a window to a great and powerful spiritual one, allowing pilgrims to explore the depths of a devotion more vast than the oceanic waters surrounding it.

If you enjoyed this piece, then you may also be interested in reading “All about Govardhan: the sacred hill of Braj”