I appreciate Dr. Thomas Blom Hansen of Stanford University explaining to me the experience of brown minorities in the US (in this podcast by Public Radio International). I really do.

I’m sure he knows exactly what it was like to grow up in the American South amidst microaggressive stereotypes about India, the country I was born in, and Hinduism, the religious tradition that I practice. Funny that he feels I am trying to whitewash textbook descriptions of Hinduism by asserting that Hindu scriptures don’t encourage caste-based discrimination. It seems to me like he’s the one with the colonialist views, equating Hinduism and bigotry – views that I am particularly familiar with, having studied Muller and Macaulay in the liberal arts departments of American universities like his, which purportedly promote post-colonial perspectives.

Conflation of social practice and religious theology

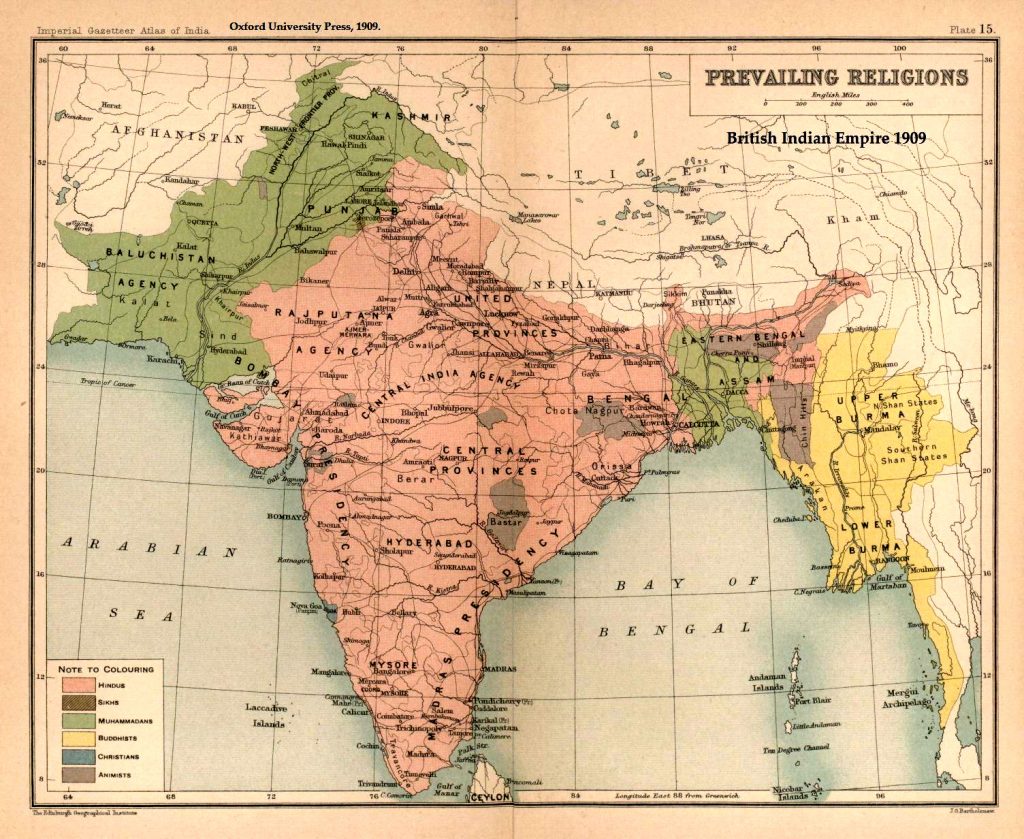

The caste system, as the western world knows it today, is a social categorization of people which is known to be predominant in India. When we in the west think of caste, derived from the Portuguese description casta in the 15th century, we think of a hierarchical, birth-based classification which discriminates unfairly against the perceived lower groups of people in society. It’s a top-to-bottom sort of thing, as Sonia Paul, reporter in the podcast, states.

This western stereotype of caste conflates two concepts – jati– based discrimination and varna. Jati is a Sanskrit term which denotes the concept of a birth-based, occupational clan or community. Over time, the thousands of jati sub-groups were rigidified into a hereditary hierarchy premised on a variety of factors. Jati-based discrimination, based on these perceived hierarchies, became prominent across all religious communities throughout not just India, but South Asia. Jati-based discrimination includes robbing a person of their basic dignity and rights as a human being, based on the community which they are born into.

Jati as an institution, on the other hand, has a social function which is much larger than birth-based discriminatory practices. One’s jati can act as a social net, connecting many extended clan members who help each other get through hard times, as is seen during the death of a family member and through the mourning process. One’s jati also provides a rich tradition of unique cultural practices and traditions, especially seen during major life events like marriage and the birth of a child. Finally, one’s jati fosters a sense of belonging and community, as is mentioned in the podcast by Paul’s father who grew up in Punjab, India.

Jati-based, or birth-based, discrimination is one of the reprehensible aspects of jati as a social institution which developed over time. Unfortunately, it is this discrimination that usually plays front and center in the mind when the phrase “caste system” is mentioned. The social practice of birth-based discrimination tied to the jati system, translated as the caste system, are never mentioned, much less condoned, by the core of Hindu scriptures, the Vedas.

A social categorization that is mentioned in the Vedas, and subsequent texts, such as the widely read Bhagavad Gita, is varna. Hindu scriptures use the word varna to describe a way of understanding the diversity of human temperaments in all human societies. Scriptures emphasize that we do not inherit our varna from our parents. Moreover, varna is fluid and can even change within our lifetime. For example, I might have more characteristics of the brahmana varna at one point in my life when I am intensely dedicated to studies and the pursuit of knowledge. But later, as I administrate and manage a household or business, I may have more kshatriya or vaishya qualities. These varnas only reflect our inherent qualities, not our parentage.

Nor is there an implied social hierarchy, as is commonly perceived. Those in each varna contribute to the betterment of society in their own ways and to the best of their abilities, all of which are necessary for a smooth functioning and harmony of society. Moreover, individuals from all varnas have the potential to attain moksha, or liberation, according to Hindu belief. Moksha is considered to be attainable for any and all humans, regardless of background or path, and it is this belief in Hinduism that promotes respect and equality for all.

While jatis could be affiliated to the four varnas according to geographic region, jatis also shifted between varnas. Over the centuries, as the thousands of jati began affiliating with the varnas, Indian society rigidified into the pervasive social structure in which caste-based discrimination arose.

Caste-based discrimination is a horrific reality across all religious communities throughout South Asia. Amongst Hindus, religious leaders and lay people alike have pointed to the fact that such practices are in violation of core Hindu teachings. As a result, many have throughout history heeded the call to combat this social evil and uplift those who have been subjugated, through religious and political reform movements as well as social projects.

Promoting Colonial Era Views

It’s no wonder that capturing the complexity of this concept, in a textbook with the reading level of a sixth grader, is a difficult task. This is compounded by the fact that textbooks are not being written in a vacuum. Publishers are working in a field where there are already many preconceived notions on topics that their materials cover. So who’s responsibility is it to facilitate the un-learning of stereotypes and misrepresentations before teaching the facts?

This is a tough question that has a multi-fold answer. Hindus as a community must learn how to eloquently enunciate the unique nuances of their religious and cultural backgrounds. Outdated textbooks must also be updated to reflect these nuances, and the general media and public must discontinue perpetuation of ignorant views.

However, it would certainly help if academics didn’t promote backwards views on already sensitive topics. By stubbornly refusing to move past their colonial viewpoints, they are the ones whitewashing history.

According to Urban Dictionary, to whitewash means to leave behind or neglect one’s own culture and assimilate to white, western culture. It’s so ironic to me that this is the term used in the caste debate and Hindu efforts to describe the overtly Hindu perspective – one which advocates a better, nuanced understanding of caste, rather than the homogenized, inaccurate understanding widely prevalent today in American society.

From the time colonial powers established hegemony over the globe, it has been the culture of the western world to equate Hinduism with caste-based discrimination. Not to mention, it has also been in the best interest of said colonial powers to exploit conflation of the two in their attempts to divide and conquer the society they occupied.

People who have actually studied Hindu scriptures know that Hinduism is a religion which promotes mutual respect and pluralism; and that Hindus believe the Divine permeates everyone and everything, regardless of class, race, gender, or other such classifications. People who don’t want Hinduism to be whitewashed realize the importance of understanding Hinduism as a religion that teaches acceptance and inherent divinity of all life forms. Especially after seeing and sometimes experiencing the egregious ill-effects of caste-based discrimination, many Hindus are working to combat this misapplication of varna in South Asian societies.

Hansen makes the analogy that teaching about the caste system is similar to teaching about slavery – it might make some uncomfortable, but should be taught. This analogy shows his callous disregard for details and his oversimplified understanding of the caste debate in California textbooks. Indeed, slavery should be taught as a part of American history in schools, but the teaching of the institution of slavery shouldn’t be tied to Biblical values and core Christian theology. That is, textbooks should not read along the lines of “Slavery in the US was and is promoted by Christianity.” This would be the more accurate analogy, if comparing caste in South Asia with slavery in the US. We all know and understand why stating “Slavery in the US was and is promoted by Christianity” is problematic, but Hansen somehow misses that.

Immigrants and Privilege

In the podcast, Hansen claims that it’s the common experience of Indian immigrant families to go through a feeling of loss of privilege when moving to the US. He states that most Indian immigrants are from certain castes which enjoy higher socio-economic privileges, and as immigrant minorities they experience a distinct loss of privilege.

I, and many other first-generation India immigrants I know, question this generalization. First of all, there’s the fact that often caste classification is not related to socio-economic class in India. Then there’s the fact that Indian immigrants come from various socioeconomic backgrounds. My family moved to the US on the H1B visa given to highly-skilled workers – but I wouldn’t say that we lived the comparatively well-off, privileged life in India that Hansen insinuates.

Hansen might be surprised to know that being a highly-skilled worker in India is not equivalent to being part of higher-class society. In fact, much of the exponentially growing middle class in India would fall into the highly-skilled worker category, but the fact is that they’re still considered middle class.

I’ve heard countless stories of hardship from my mother and father, who both began their careers in IT in India. Contrary to what Hansen might believe, they did not grow up in the lap of luxury. They had to work in rural hometowns to get an education, and finally moved to densely populated, metroplex city hubs to establish their careers amidst a rat-race of competition. And they’re not the only ones — many immigrant families have faced similar challenges in India before moving to the US.

So this analysis of Hindu Indian immigrants’ experience in the US – their sense of unease after moving, because of a sense of lost privilege – is an unsubstantiated fallacy. For Hansen to say that this feeling of uncomfortability motivates Hindu Indian immigrants to want to erase the caste system from descriptions of Hinduism in textbooks is entirely bereft of logic. And anyways, no one’s working to erase knowledge or recognition of the caste system, as Hansen disingenuously asserts. Hindu Americans simply want to provide an accurate, balanced perspective on the social phenomenon, one which takes into consideration the nuances regarding caste and varna outlined above, which are unfortunately absent in current textbooks — as are the centuries of reform movements driven by Hindus to counter caste-based discrimination.

Current textbooks, by the way, follow standards prescribed almost twenty years ago. While the standards for other subjects areas such as math and science have gone through revision and updates, with new findings in academic research, the history and social studies standards for California textbooks have not been updated since 1998. Even those standards are questionably compiled, according to a former California teacher: Bradley Fogo of the Stanford History Education Group notes that the development of history and social science standards was fraught with politics and the privileging of certain groups over others, creating an uneven and almost exclusionary set of standards.

Though many understandings of historical society have been more sensitive to multiple viewpoints and thus better reflected in textbooks, perceptions on Ancient India and Hinduism have not moved past outdated views established by the British Empire. Hinduism is constantly defined in relation to discriminatory social practices, despite the fact that discrimination goes against Hindu core teachings and that caste is widely misunderstood. I question who’s actually ‘caste blind’, to use Hansen’s own words – who doesn’t see the truth about caste?

Moving forward

Hindu Americans also want to make sure their voice is a part of the dialogue which then shapes perceptions of their religion, home country (for many, but not all), and by association themselves. By incorrectly judging their experience, and then furthermore trying to silence their voice by denigrating them, Hansen is blatantly whitesplaining the situation.

It’s surprising to me that Hansen is the Reliance-Dhirubhai Ambani Professor in South Asian Studies at Stanford University. Well-meaning philanthropists in India should re-evaluate how their money is being used to perpetuate colonial era views instead of facilitating progress.

As for the reluctance to acknowledge the caste system on the part of immigrants – perhaps this is because people observing the system, like Hansen, conflate the multiple nuanced aspects of caste into one homogenized monster of a concept, which then subtly perpetuates a negative worldview of their entire culture: the caste system, when brought up in conversation by westerners, usually refers just to birth-based discrimination, and is perceived to define life as a Hindu in India.

Yet, the reality is that birth-based discrimination does not comprehensively define the jati system that South Asians know of – in the Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh communities, and both within and outside India. This practice of jati is then portrayed as a core teaching of Hinduism, when that’s not the case. Varna is mentioned in Hindu scriptures, but in the context of maximizing an individual’s potential in society, given their unique talents, temperaments, and qualities, and is neither based on familial birth nor fixed throughout life.

So why would Indian Americans want to avoid the topic of caste? Maybe because they know the complexities associated with the issue, and that they are walking into a minefield of misrepresentations, stereotypes, and falsities regarding the subject when it comes up. True, avoiding the topic is not a solution. Hindu Americans, specifically, must put a confident foot forward to both understand the nuances, and work to make this understanding widespread. Many groups, including the Hindu American Foundation, are doing notable work in this regard.

However, assuming that Indian Americans are uncomfortable with their loss of privilege in American society is not a fair position with which to approach the issue. I humbly encourage Dr. Hansen to adopt postcolonial views on Indian history, and perhaps read more about caste with regards to Hinduism, so that erroneous, misinformed perceptions on these subjects are not propagated further.