“Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music. It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down.” — Martin Luther King, Jr. — (from his essay in the program of the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival)

From a historical perspective, 1960s jazz is most often placed within the context of the Civil Rights Era, enshrined as a soundtrack for liberation in the storm of the period’s political oppressions. And how could it not, when the face of the movement himself practically hailed it as so.

Yet, when one delves into available examinations of the subject, discovering in detail about the Black artists who boldly broke the boundaries of musical and societal convention in pursuit of integrity and justice, one can’t help but feel like something is being left out. Something important.

If, as King claimed, jazz truly brought strength and serenity to the struggling when spirits were down, then the question naturally arises: what soothed and charged the spirits of those who were able to transmit expressions of such restorative power?

Upon further investigation, the answer that’s found, unsurprisingly, is beyond political. It’s of a sacred nature, as it only could be. And not just of the Judeo-Christian kind, but of a tradition far more unexpected and far more influential than you would think.

Of Hinduism. How?

Prior to the mid-century, family, church, and neighborhood were closely tied, as communities generally worshiped in cultural enclaves that fostered rigid religious identities rooted in class, race, and region. Propelled, however, by a postwar generation’s push for wider social mobility, these identities began deteriorating, leading to the development of a different one.

Concerned with the attainment of an inner realm of unifying truth, meaning, and authentic self that transcended caste or creed, a new spirituality of “seeking” defined many of the time, who consistently turned to the investigation of alternative traditions — mainly of the Eastern persuasion.

Faced with rising economic and political hardships, and their struggle for civil rights, much of Black America embraced the trend with even greater urgency. And, equipped with the impassioned vigor of their innovative edge, jazz luminaries played a pivotal role in leading the charge, sparked, in large part, by an unlikely catalyst. Legendary sitarist, Ravi Shankar.

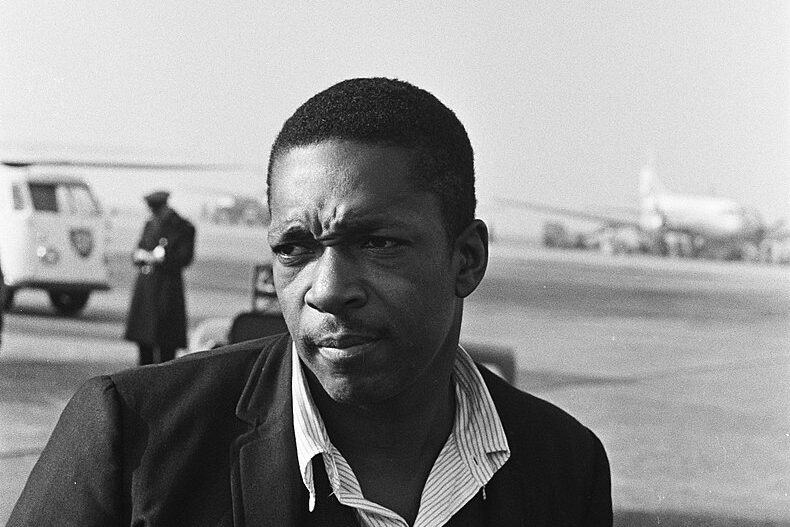

During his early years of touring and recording in the US in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, while he was still an unknown, it was they who took notice, flocking to his concerts, absorbing his knowledge, and collaborating with him. Though several among this trailblazing cohort are worth mentioning, the one of greatest significance, without question, was John Coltrane.

A highly accomplished saxophonist who gained prominence as a member of Miles Davis’ quintet in the ‘50s, Coltrane also spent much of the decade in the throes of a heroin addiction, until undergoing what he described to be a “spiritual awakening” that led him away from the drug towards a divine quest to uplift others through his playing.

Emphasizing the realization, he said: “I would like to bring to people something like happiness. I would like to discover a method so that if I want it to rain, it will start right away to rain. If one of my friends is ill, I’d like to play a certain song and he will be cured; when he’d be broke, I’d bring out a different sound and immediately he’d receive all the money he needed. But what are these pieces and what is the road to travel to attain a knowledge of them, that I don’t know. The true powers of music are still unknown. To be able to control them must be, I believe, the goal of every musician. I’m passionate about understanding these forces. I would like to provoke reactions in the listeners to my music, to create a real atmosphere. It’s in that direction that I want to commit myself and to go as far as possible.”

When he thus heard Shankar’s compositions, which not only had the same improvisational freedom as jazz, but was aimed at something more, or as the sitarist put it, “to feel the sweet pain of trying to reach out to the Supreme, to bring tears to the eyes, and to feel totally peaceful and cleansed,” he became hooked.

Plunging into a headlong exploration of Indian classical music, he was particularly intrigued by its concept of raga — melodic frameworks designed to invoke specific rasas, or emotional dispositions in the mind’s of listeners.

Going deeper, he learned all about the life and teachings of Paramahamsa Yogananda and Sri Ramakrishna, and read a medley of Hindu texts like The Bhagavad Gita. Before long, his Indian leanings started shaping his own work, made obvious to the most casual of fans in titles like Meditation, Om, and India, along with several others.

As his music grew increasingly popular, so did his notion of musical transcendence, inspiring many jazz musicians of a younger generation, including the likes of John Mclaughlin.

Following in Coltrane’s footsteps, who he’s cited as one of his personal heroes, Mclaughlin also met and collaborated with Shankar, and even became a disciple of Indian guru Sri Chinmoy. Eventually forming a band called the Mahavishnu Orchestra, named for Hinduism’s god of preservation, and another called Shakti, named for the feminine aspect of Hinduism’s conception of the Divine, his impact ascended past the confines of jazz.

As Jeff Beck — who according to Rolling Stone Magazine, is one of the top five guitarists of all time — once said, “John Mclaughlin has given us so many facets of the guitar. And introduced thousands of us to world music by blending Indian music with jazz and classical. I’d say he was the best guitarist alive.”

Hence opening the minds of countless to Coltrane’s spirit of music, and the Hindu tradition that influenced it, John Mclaughlin’s hand in advancing the saxophonist’s legacy has been immeasurable.

Of course, to discuss this legacy and not mention his wife, Alice Coltrane, would be a serious disservice. It was she, after all, who advanced it, perhaps, more than anyone.

A talented musician in her own right, on top of being his partner, she was his pianist, and therefore with him almost every step of the way during his Hindu-fueled musical journey.

Continuing to play and record music that employed elements of Indian spirituality after his untimely death from liver cancer in 1967, she ultimately embraced Hinduism on a whole other level, especially after 1970, when she met her guru Swami Satchidananda.

Captivated by his focus on the equitable but personal sacred potential of all, a philosophy that echoed a similar spiritual sentiment to that which her husband pursued, she accompanied him to India, a trip that proved to be profoundly transformative.

In the years that followed, she evolved into an advanced disciple of his, taking the name Turiyasangitananda and becoming the head of an ashram in the Santa Monica Mountains of California, which tragically burned to the ground in 2018 in a wildfire. A prominent female spiritual leader in America at a time when they were almost always men, her teachings, echoed by her progressively Hindu albums, like Divine Songs and Infinite Chants, drew in followers of numerous backgrounds.

And after her death in 2007, her son Ravi (named for the sitarist who helped catapult her and her husband’s spiritual voyage in the first place), is carrying the torch, connecting people from everywhere to spirituality through his own music.

As that torch continues to burn bright, so does the dream of civil rights, for it’s stoked by the same Hindu tradition of love, unity, and open-mindedness that helped power the freedom fighting jazz players of the ‘60s.

If you enjoyed this piece, then you may also be interested in reading “How Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan brought Indian classical music to America”