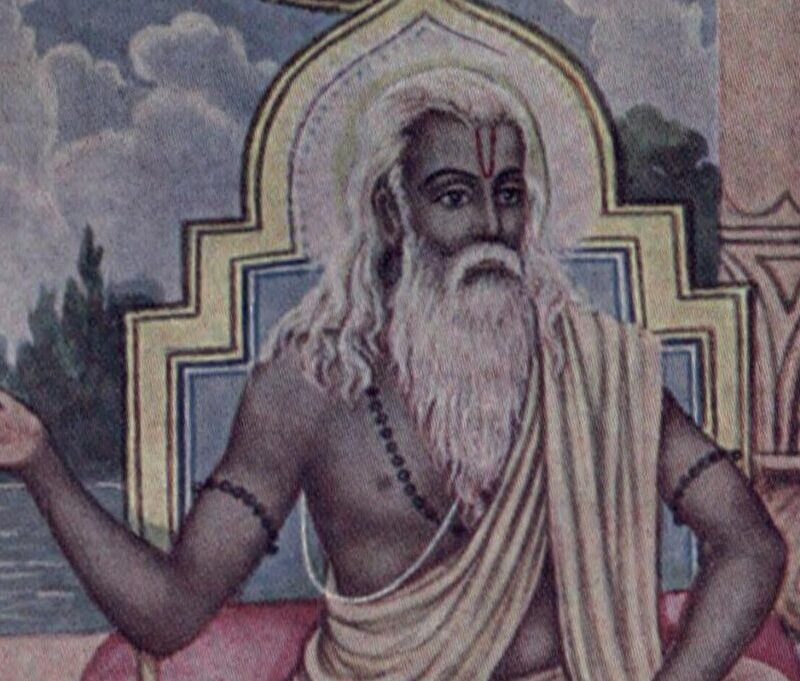

The birth of Guru Nanak

1) He lived during a period of religious unrest

When the founder of Sikhism took birth more than 550 years ago in the small village of Talwandi, roughly 40 miles southwest of Lahore, India was a land divided.

Though predominantly made up of those who practiced the Hindu Dharmas (the collection of spiritual paths native to the region), Islam was also firmly established in the country, following centuries of conquests by the Delhi Sultanate and an impending Mughal takeover. Because of this, the upbringing of those raised at that time and place was more or less destined to be one shrouded in tumult, fueled by Hindu-Muslim tension, and all of the inequity, hypocrisy, and corruption that came with it.

And yet, upon looking at the newborn’s horoscope, as was the custom of the day, Hardyal, the village pandit, saw not a life of discord and division, but harmony and brotherhood. A leader of men, it seemed this person would be revered by Hindus and Muslims alike, uniting them in love, prayer, and universal fellowship. So confident, in fact, was Hardyal in his proclamation, he called him “Nanak,” a name common to both religious traditions, among whom, he said, the infant would grow up to look upon with equal vision.

Whether such a statement would actually come to pass, most paid little mind, including his father, Mehta Kalu, a practical and worldly man whose simple hope was for his son to attain a secure and stable occupation. For many looking back, however, the pandit’s words were prophetic, providing a lens through which to view the events of Nanak’s formative years, all in preparation towards his ultimate future.

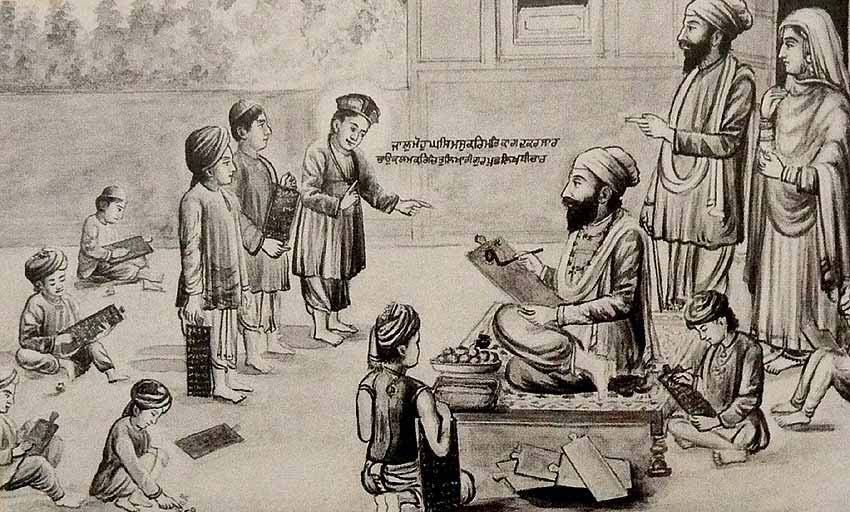

Guru Nanak as a boy in school

2) His spiritual inclinations manifested at an early age

In some ways, Nanak appeared much like others as a child, enjoying time with family and friends amidst the agrarian lifestyle of the surrounding area.

When, however, his father sent him at the age of 5 to study with local teacher Pandha Gopal, his extraordinary spiritual acuity swiftly began to show itself, manifesting in poetic compositions of surprisingly sophisticated expression. Impressed, Gopal eventually referred him to Pandit Brijlal, a brilliant scholar who went on to expose him to the Sanskrit classics. But after a couple years he too stopped teaching Nanak, declaring the boy a sacred embodiment of wisdom, who had nothing left to gain from him.

Nevertheless, Nanak continued to feel spiritually restless, and so began learning under Qutab-ud-Din, a local maulvi who taught him Persian and Arabic. Within a couple more years he was practiced enough to start studying Islamic texts, incorporating what he absorbed from them into his own compositions. And before long, he was out in the fields and jungles, encountering ascetics of diverse backgrounds while tending to his family’s cattle, engaging in a wide array of spiritually charged discussions.

As his immersion in such topics, therefore, grew deeper, so did its effect on how he approached the world. Indeed, once his father asked him to find a good deal in town, handing him money, but on his way Nanak came upon a group of impoverished sadhus and gave it to them instead. Though reproached by his father, he was firm in his reasoning, convinced that there was no better deal than a selfless one of compassion.

Yet, despite his renounced disposition, he grew older and the time soon came for him to take up a life of responsibility. Moving east to Sultanpur, where his sister and her husband resided, he accepted a job in charge of the granaries and stores of the local chieftain, and was arranged to be married shortly thereafter.

Thus starting a family, he and his wife had two sons, as he, for a while, seemed to live like that of a worldly householder. But, of course, this would only last so long. Drawn by the magnetic power of his spiritual will, fate would appear with other plans, propelling him towards a destiny he’d forever be remembered for.

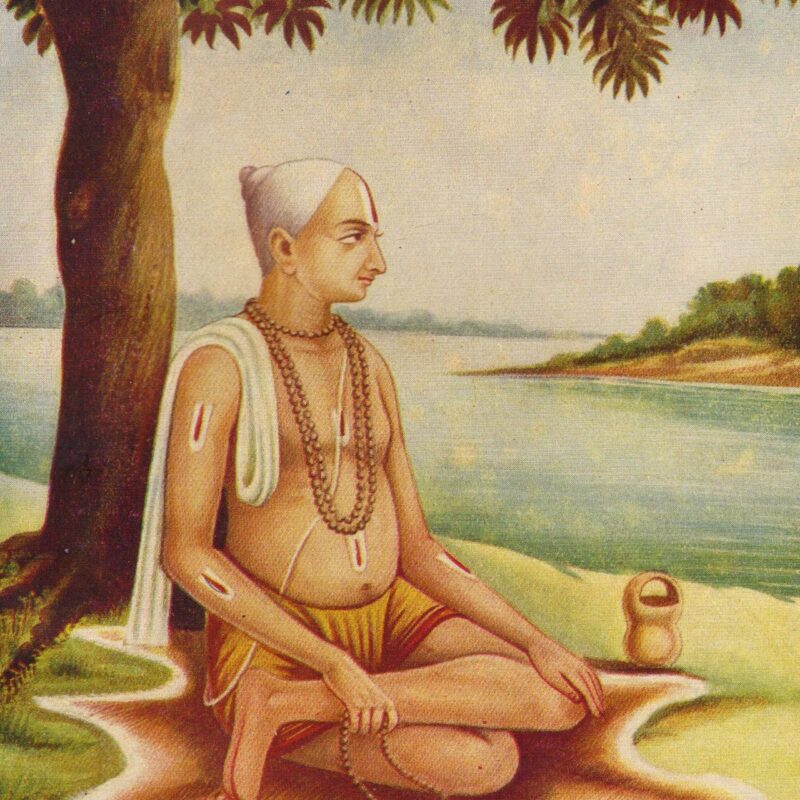

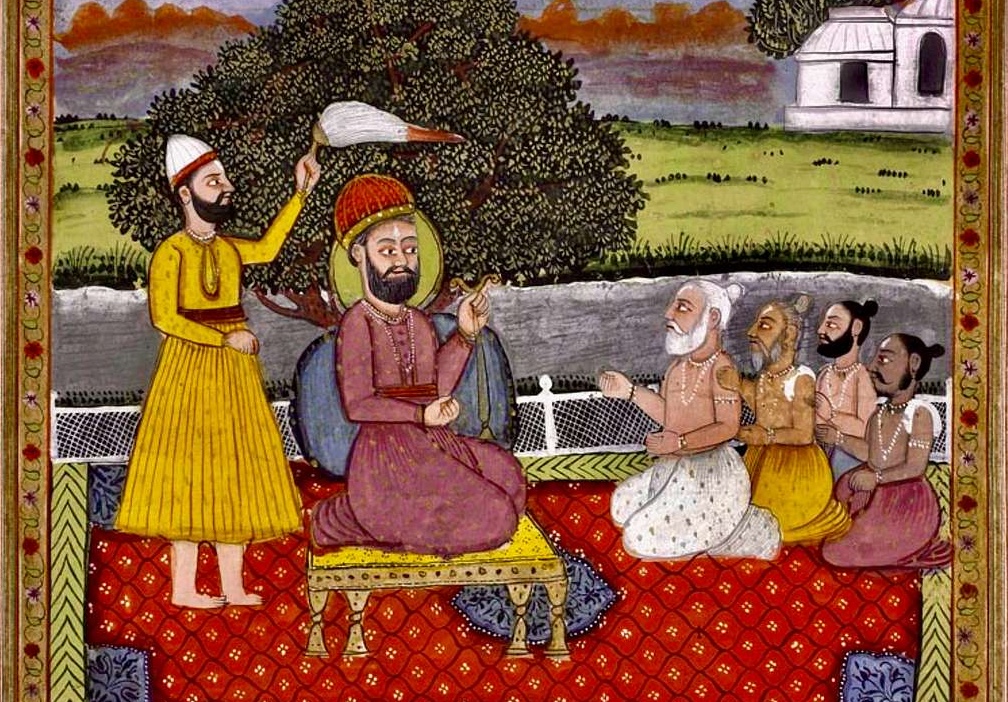

Guru Nanak talking to ascetics by the water

3) He espoused the spiritual oneness of all

One day, while taking a bath in the Kali Bein, a small rivulet that flowed near his home, Nanak mysteriously vanished and was feared to have drowned. Three days later, however, he miraculously reappeared, emerging from the banks in quiet tranquility.

According to accounts, he’s said to have had a profound revelatory experience, during which he was ushered into the presence of the Supreme Being and given a transcendent vision of reality. Washed in a permeating force that flows through all aspects of creation, he felt an overwhelming sense of spiritual oneness, connecting everyone and everything beyond the temporary divisions of material differences. When he therefore broke his silence, stoic and grave, he addressed those around him with poignant clarity, declaring in bold fashion: “There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim.”

Yet, to simply verbalize this realization to those near him wasn’t enough. To make the world a better place, as many as possible needed to become cognizant of their spiritual connection with each other, and not just in the theoretical sense. They needed to feel it, as he had — to feel the divine power that could create kinship even among those who had nothing in common. The feeling of true, unwavering, unconditional love.

Needless to say, it wouldn’t be easy. Such a feeling, after all, doesn’t just arise in one without effort. True love — the kind that takes root in the heart and endures, regardless of time, place, and circumstance — has to be cultivated, nurtured through the disciplined practice of service. Thus arranging for his family to be looked after in his absence, Nanak, a born Hindu, took his life-long friend Mardana, a born Muslim, and left his home, embarking on the first of many travels.

Leading by the example of their own unlikely friendship, the two journeyed throughout the land, spreading this message of egalitarian love through the strength of many deeds and services. And despite numerous challenges, they moved ahead without hesitation, paving a sacred path to the Divine, free of all disparities.

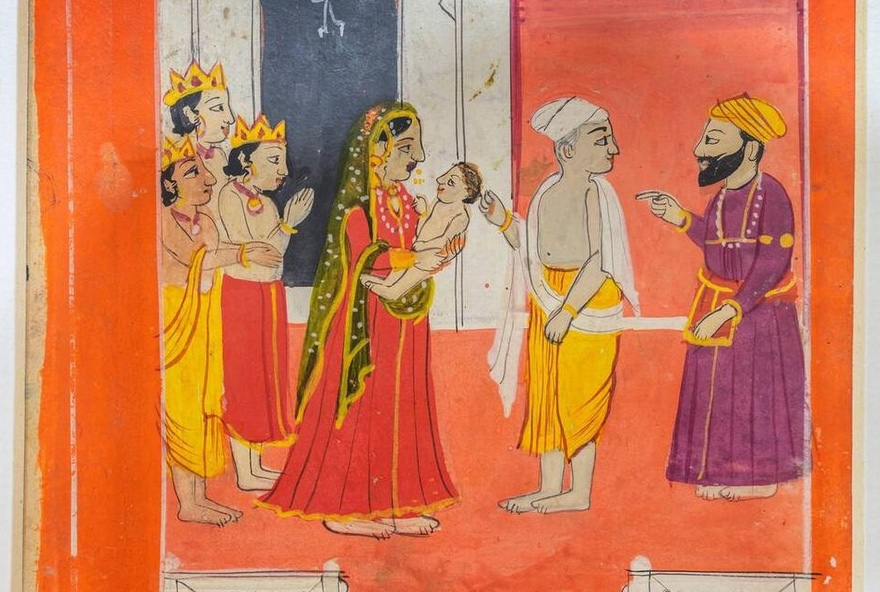

A follower in discourse with Guru Nanak

4) He traveled extensively throughout India

Nanak, as described in a medley of historical texts and literature, undertook four major journeys throughout India and beyond, covering thousands of miles over a roughly quarter-century period.

Dressed in a strange garb of Hindu, Muslim, and common-folk attire, he moved as a symbol of universality, going all the way to Assam in the east, present-day Sri Lanka in the south, Mount Kailash in the north, and Mecca in the west. Trekking from mountains to jungles, to oceans, to deserts, he saw the smallest of villages, the greatest of cities, the tallest of mosques, and the humblest of temples.

He rejected all rituals, customs, and hierarchies that served as rigid tools of social disunity, and called out the hypocrisy of the smug, standing up to the most formidable of oppressors. Once, he even spoke out against Mughal Emperor Babur, convincing him to release the survivors of a town his army brutally plundered. And later he initiated a community of his own, where the marginalized could start afresh, living among others in peace, harmony, and spiritual fortitude.

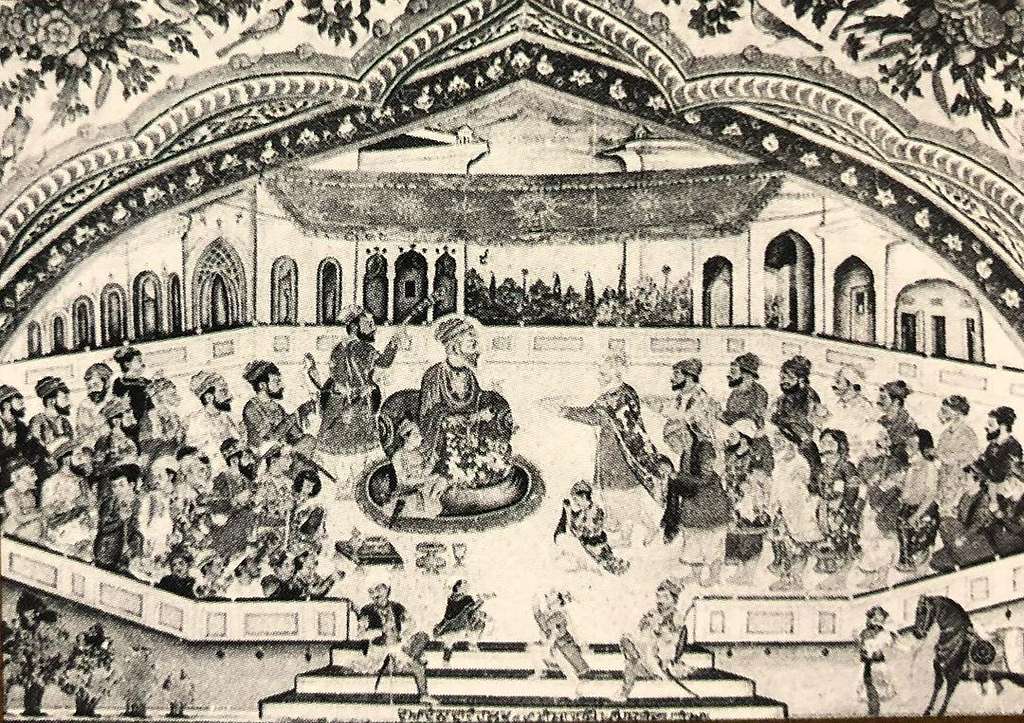

Indeed, it was here, in Kartarpur, the “Abode of the Creator,” he ended his travels, settling with his family after their long separation from each other. Laying aside his pilgrim apparel, he clad himself in working clothes, and dove into the labor of his vision, helping to establish the infrastructure of what would eventually become a greater city. This, however, didn’t mean he had adopted the mind of a worldly man. He simply believed people didn’t have to withdraw from the world to be spiritual. That as long as they selflessly performed their duties in service to others, they could attune themselves to the will of the Divine, making similar progress to that of a renunciate.

What truly mattered, in other words, was mindset and intention, which is why he made sangats, or daily congregational prayers, an integral feature of the city, guiding all in regular remembrance and absorption of their sacred focus. And why, going further, he instituted the tradition of langar, serving free meals to everyone and anyone, on the one condition they agreed to dine on the floor together, honoring each other as equals.

Thereby establishing the physical and spiritual foundations of the city, Nanak poured the final 18 years of his life into Kartarpur, drawing many of various backgrounds and regions under its egalitarian promise of inclusivity. As the community therefore grew, so did the size of his following, cementing his illustrious status as “Guru,” a title he would ultimately pass onto another.

And when that time finally came, indicating the end of his earthly pastimes, he approached it with the same equal vision he did everything else, selecting a successor based on merit over familial relation. Thus entrusting Bhai Lena, a loyal and qualified disciple to carry on the torch of his mission, Nanak passed away, having fulfilled his purpose.

Guru Nanak’s followers assembled together

5) His legacy lives on despite centuries of persecution

Covering a more than 200-year stretch, there were 10 gurus in all, as the last, Gobind Singh, ultimately brought the line to an end, conferring eternal guruship to the Guru Granth Sahib, a sacred compilation of Sikh hymns and teachings.

It was at this time, in 1708, Sikhism’s formative stage thereby concluded, its precepts, customs, and institutions, having attained their final form. And though, overall, it was a triumphant era of success, where the tradition rose from a small community of followers to a significant social and religious force in northern India, there were many challenges along the way, due, in large part, to persecution by Muslims.

Generally speaking, the genesis of this persecution can be traced back to the time of the fifth guru, Arjan, who was imprisoned, tortured, and executed after his successes at increasing Sikhism’s prominence kindled the wrath of Mughal authority. A pivotal event that led to the militarization of the Sikh community, the two sides engaged in armed conflict for about 150 years, during which untold horrors tragically unfolded.

Tegh Bahadur, the ninth guru, for example, was publicly beheaded. Gobindh Singh, the aforementioned last guru, was slain by an assassin. Singh’s two older sons, Ajit and Jujhar, were killed in battle. His two younger sons, Zorawar and Fateh, were bricked into walls alive. His disciple, Banda Singh Bahadur, was skinned alive, his limbs cut off and eyes gouged out. And when Mughal power went into decline, the tyranny continued.

For while Sikhs managed to endure, establishing their own empire in the late 18th century, they were soon annexed by the British, resulting in yet another period of social unrest, and the ultimate partition of India. An event that triggered one of the largest mass migrations in history, the chaos, violence, and brutality that ensued forced countless to flee their homes, including millions of Sikhs who lost sacred sites, like Kartarpur and Talwandi, to the newly formed Pakistan. Thus exiled from much of their homeland, most of them settled in northern India, as those who remained in Muslim-majority regions, like Afghanistan, were also driven out over time.

But don’t be fooled into thinking this means Sikhism hasn’t been able to prosper. Imbued with the resilience of their tradition’s founder, they rebuilt their lives, creating new businesses, farms, and institutions that have made invaluable economic contributions to the country. Eventually spreading abroad, their diaspora has grown significantly in Canada, the UK, and the US, as their global influence too has risen dramatically.

30 million strong, their greatest contribution, however, remains their spiritual one, centered around the expansion of sangats, langars, and the equal treatment of every individual. In all they have been through, these are the principles that have kept them moving forward, advancing Guru Nanak’s legacy with love, compassion, and the inexorable power of his will.