Queen Maya, Buddha’s mother, gives birth to him in a grove while traveling to her parent’s home.

1) He was born a prince

It was roughly 2,500 years ago, on the full-moon day of Vaisakha (April-May), that the Buddha came into the world, swift and unyielding.

His mother, Maya, chief queen of Suddhodana (king of the Sakyas, on the Nepalese frontier), was traveling to her parents’ place in Devadaha, where she was meant to give birth, when fate stepped in with other plans. Fifty-six and ladened by the final stage of pregnancy, she had stopped to rest at a grove in Lumbini along the way, but struck suddenly with the symptoms of impending labor, was forced to pivot. Thus summoning her female attendants, they cordoned off the area with curtains, and she delivered the boy then and there, in the cool shade of a flowering sal tree.

Five days later, after he was brought home to the capital of Kapilavastu, his father held a name-giving ceremony, during which eight pandits were invited to comment on the newborn’s future. Observing all the major signs of auspiciousness, the first seven held up two fingers, indicating he would either become a universal monarch, or renounce the world and attain enlightenment, while the last and wisest held up only one, declaring, in fact, the boy had but a single fate, and it would not be the former.

In any case, he was given the name Siddhartha, meaning “one who has achieved his purpose,” as his father, desperate for him to remain at home, did all he could to make sure it would not be as the last pandit insisted. Despite Maya’s untimely death just two days later, Siddartha, therefore, was given anything and everything he required to stay happy, without ever a need to go beyond the boundaries of the palatial complex.

Amidst three palaces all his own, each built for the summer, winter, and rainy seasons, respectively, he was nurtured till manhood in extreme luxury and refinement, provided the finest silk, food, servants, and entertainment. Receiving, also, a princely education, he became skilled in many branches of academic and martial knowledge, after which he was betrothed and married, so he too might one day extend the family line.

Hence groomed for what his father hoped would be a great and prosperous rulership, Siddhartha lived out his youth completely unaware of the issues that plagued the world outside. But, of course, this was all to change, for his destiny, indeed, had but one track, and it wouldn’t be long before he was on it.

A young Siddhartha Gautama witnesses the four signs of old age, disease, death, and asceticism while traveling outside of the palatial complex.

2) He renounced the throne to become an ascetic

As time wore on, Siddhartha, despite his many pleasures, grew restless in palace life, and so began seeking solace outside the gates in the royal gardens.

On one occasion, while being driven by his charioteer, Channa, they happened upon a feeble-looking man, hunched, wrinkled, and decrepit with age. Having never seen such a sight, Siddhartha asked about the person, and learned, to his shock, that he was but elderly, and that all, including the prince himself, would eventually look like that one day. Shaken by this revelation, he became absorbed in processing the weight of its meaning, when, on a second outing, they encountered another man, this one weak, emaciated, and in the throes of physical suffering. Inquiring again, he was told this person was sick, and though currently healthy, he too would no doubt be affected in a similar way, as would everybody.

Disturbed all the more, he felt increasingly pensive, as on a third excursion, they came across a funeral procession, and saw, amidst a group of mourning kinsmen, a corpse being carried to cremation. Wondering once more what he was looking at, the prince was duly informed all about death, and the inevitable fate he and every other being on the planet was ultimately destined for. Plunged, therefore, deeper into a solemn state of confusion, Siddhartha thought continually about the miseries of the world, confounded at how he had somehow been living his life, completely and utterly oblivious to them.

It was at this point in his contemplations that they went beyond the gate for yet a fourth time, passing one more man who, unlike the others, showed no signs of death, pain, or tribulation. Calm, aloof, serene, and independent, his measured countenance captivated Siddhartha who, upon questioning, discovered he was an ascetic, or someone who had left his family and possessions in full-time pursuit of life’s deepest truths.

Struck by the notion, the prince returned home, lost in thoughts of renunciation, which progressively consumed him, even after his wife became pregnant and gave birth to a son. Realizing, eventually, he could no longer continue living in the capital, cognizant as he was now of the fragile state of the human condition, he decided that he too would become an ascetic.

Thus cutting off his long locks and donning the hermit’s dress, he slipped away in the dead of night, taking a final look at his sleeping family. Determined to find deliverance from the unforgiving trident of old age, disease, and ultimate death, he was ready to do whatever it took — and not just for himself, but for all of his loved ones.

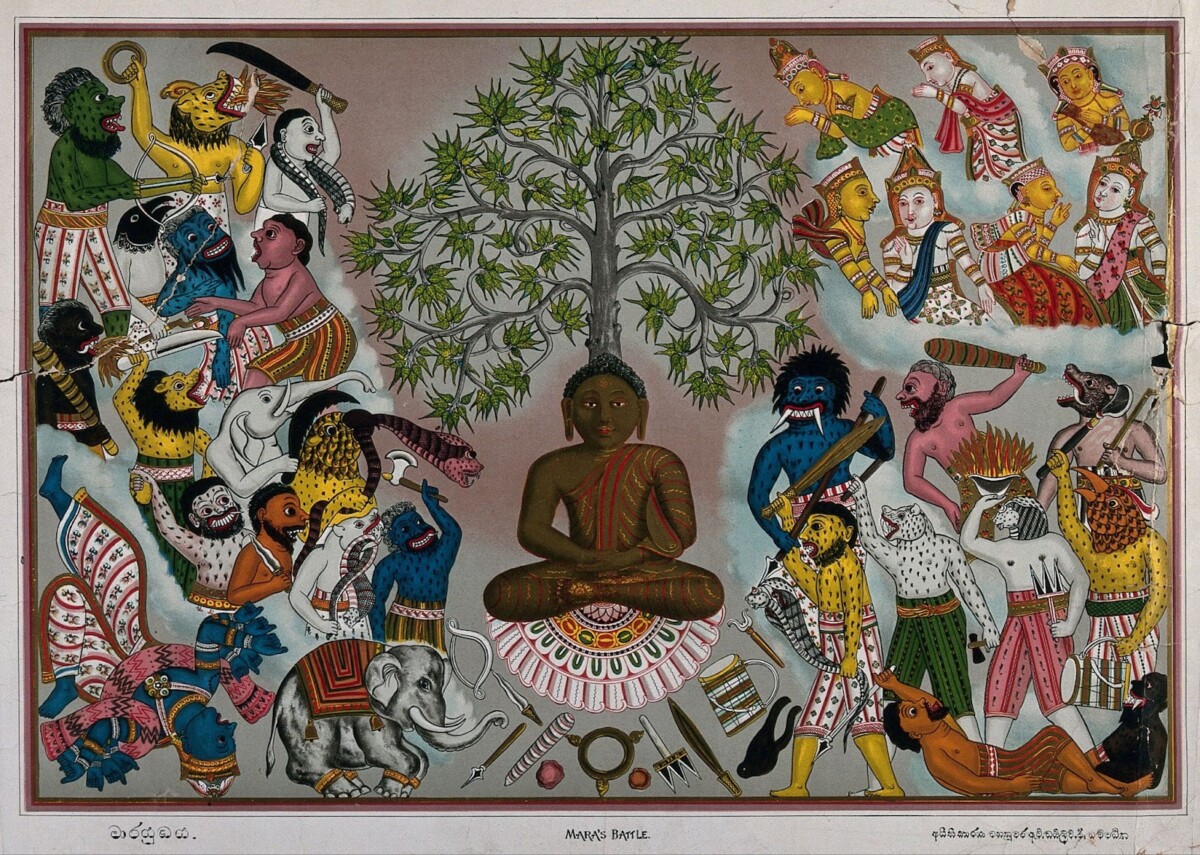

Siddhartha Gautama sits and attains enlightenment under a pipal tree.

3) He attained enlightenment by taking the middle path

At first, Siddhartha trekked to Rajagriha, the illustrious capital of Magadha, famous as a spiritual center of learning. There, he sought Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta, two masters of meditation, who taught him how to reach advanced stages of mental concentration and peace.

Feeling, however, these states were but temporary windows of tranquility that lacked a permanent release from the worldly entrapments of suffering, he soon left them, traveling, in due course, to the banks of the Nairanjana River, in the Uruvela forest at Gaya. A hub for renunciates, with clear waters and quiet groves conducive for rigorous spiritual practice, it wasn’t long until he was joined by five other sages, who felt drawn to the power of his unwavering will.

Propelled, therefore, by the force of such company, he engaged in severe austerities, struggling to conquer the demands of his body in hopes of unshackling his mind toward liberation. But when, after six years of little food, water, or comfort, his discipline left him emaciated, at the edge of death, and no nearer his goal, he discontinued the self-torture, causing the sages to abandon him, thinking he had given up on his endeavor to resume a life of gluttony.

Yet determined as ever to see his mission through, he didn’t indulge, but accepted, rather, enough nourishment only to recover his health, so that he might make one final push for enlightenment. Thus taking shelter one evening of an expansive pipal tree, he sat cross legged and fell into meditation, resolving not to rise until he attained the spiritual freedom he was looking for.

Renowned as his night of awakening, the concentrative state he entered, needless to say, didn’t end in just peace and tranquility like it had so many times before. Imbued, now, with the sharp discernment of his renewed strength and vigor, he experienced deep insights on the true nature of existence, progressing through his revelations in three profound stages, described in traditional sources as “watches of the night.”

During the first watch (6 p.m. to 10 p.m.), he gained remembrance of his previous lives, giving him an understanding of samsara, or the perpetual cycle of birth and death, and all of the futility that comes with it. During the second watch (10 p.m. to 2 a.m.), his vision grew even wider, as he saw how all beings were lost in this cycle, moving from one life to the next according to their karma, or the cause and effect of their various deeds. And during the third watch (2 a.m. to 6 a.m.), he realized the Four Noble Truths, or that the cycle of karma was full of suffering, that such suffering was caused by selfish desires, that by eliminating these desires one could eliminate suffering, and that the Middle Way was the method by which to do this.

A practical approach between extreme indulgence and extreme austerity, the Middle Way became known also as the Noble Eightfold Path, centered around “right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.” Designed, in essence, to help people cultivate the wisdom, harmony, and focus needed to transcend life’s volatility and achieve worldly detachment, it was a practical guide that could be used by anyone, of any time, and any place.

All that was needed was for somebody to show the way. And Siddhartha, having come to the completion of his awakening, emerging as the Buddha, or “Enlightened One,” was finally ready to do it.

Siddhartha Gautama, now revered as the Buddha, teaches others how to attain enlightenment

4) He spent 45 years propounding his realizations

The first people Siddhartha thought of when considering who to spread his realizations to were his old teachers, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta. When, however, he discovered both of them had since passed, he decided, instead, to go to Varanasi, where the five ascetics who abandoned him had taken up residence.

No longer regarding him as a respectable mendicant, his old friends, upon his distant approach, had initially resolved to ignore him. But as he grew closer, revealing the undeniable power of his dignified presence, they, struck by wonder, submitted to his teachings, becoming the first monks of his order of dharma, or spiritual truth.

Small but burgeoning, this order swelled in swift time, as a wealthy young man named Yasa, who lived in the area, happened upon them and became attracted by their way of life, inspiring his friends and family to join too. Suddenly more than 60 in number, Siddhartha dispatched, thereafter, his new followers in various directions, charging each of them with the duty of sharing what they had learned, so more like them might similarly benefit.

Having thereby sown the first seeds of his movement, he decided to go to the place where his spiritual practice began, Rajagriha, after Bimbisara, the king of Magadha, invited him upon hearing of his enlightenment. Engaging with a medley of people along the way, the most noteworthy of Siddhartha’s exchanges took place on the banks of the Nairanjana, where he met and instructed three ascetic brothers, Uruvela, Nadi, and Gaya Kassapa — each with disciples of their own, numbering 500, 300, and 200 respectively.

Accompanied, therefore, by over 1000 fresh aspirants, he proceeded to see the king, who was so impressed, he also became a follower, donating a bamboo grove, which served as Buddhism’s first makeshift monastery, providing a place for the community to practice and grow. Residing, as such, in Magadha for some time, Siddhartha accumulated yet more followers, including two named Maudgalyayana and Sariputra, whose knowledge and wisdom led them to become his chief students, bringing 250 more along with them.

Equipped, thus, with a robust base, and the leading disciples needed to help guide the order, he continued to espouse his teachings throughout northern India, returning even to Kapilavastu, where he convinced many of his friends and family to join. From Vaishali in the east to Kuru (Delhi) in the west, he gained thousands of followers over a 45-year period, and when, at 80, he knew his time on earth had finally come to an end, he passed away as expected, embracing death with dignity, detachment, and absolute fearlessness.

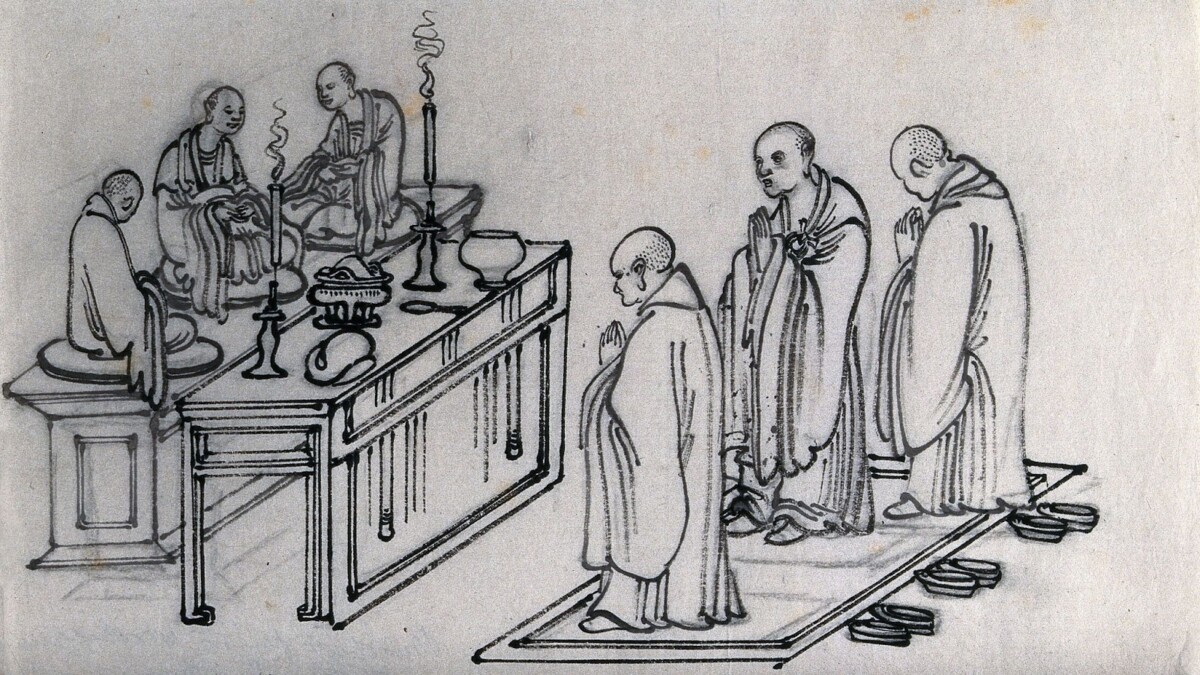

Buddhist monks worshiping at a shrine

5) His teachings have transcended the annals of time

Following Siddhartha’s death, his disciples continued to share his teachings, organizing and systematizing his movement over the next couple hundred years. Yet, it wasn’t until the third century BCE, when Ashoka, ruler of the Mauryan Empire, took interest, that Buddhism really started to flourish.

Eight years after assuming power around 270 BCE, he led a military campaign against the coastal kingdom of Kalinga. And though he was victorious, securing a larger domain than any of his predecessors, the conquest resulted in the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives, leaving him deeply troubled. Haunted by the suffering, death, and bloodshed of war, the commitment to expand his territory swiftly dissipated from him, as he sought solace in the teachings of Buddhism, and its emphasis of non-violence.

Becoming a patron of the dharma, he built stupas (Buddhist shrines) and monasteries across the expanse of his empire, which extended from the Himalayas in the north to Tamil Nadu in the south. He carved edicts into stones and pillars at pilgrimage sites and along busy trade routes. And he dispatched emissaries in every direction, reaching places like Syria, Greece, and Sri Lanka.

As Buddhism thus spread swiftly under his reign, so did it after, getting larger and more diverse over the next few centuries with followers in different regions interpreting its aspects in various ways. Despite, therefore, being forced to India’s background during the middle ages with the spread of Islam, Buddhism continued to prosper in other countries, growing increasingly popular in Central and Southeast Asia.

By the 20th century, it reached the West, as it rose to the status of world religion. Now boasting more than half a billion followers, it’s had a dramatic impact on global culture, shaping art, architecture, literature, medicine, music, and an array of social customs. Ultimately, fueled, however, by the depth of its philosophical focus, followers make sure to honor Siddhartha’s legacy by the strength of their practice, putting forth extra effort on Vesak, which commemorates his birth, death, and enlightenment, and Bodhi Day, which places further emphasis on his enlightenment.

Meditating, reading from sacred texts, and performing acts of kindness, some even go on pilgrimage to the very tree where he attained liberation, paying their respects to the profound significance of the area.

Without it, after all, the Buddha as we know him wouldn’t have existed. And without him, the world certainly wouldn’t be the same.