In one sense, the essence of Hindu philosophy is simple. Every individual is an embodied eternal atman (spirit or soul). Being distinct from the body — including its extended attributes like race, gender, and sexual orientation — every atman originates from the same Divine source and is therefore part of the same spiritual family, deserving the dignity of love, respect, and equal treatment.

But morality is a complex topic, and some of Hinduism’s most highly regarded figures have grappled with its nuances. Though all moral codes espoused in the religion are meant for the ultimate purpose of unconditional love and acceptance, India’s great epics convey numerous examples in which even well-meaning people have missed this purpose in their determination to strictly follow the “rules.”

Perhaps the most famous example is that of Bhishma, whose treatment of Amba, a princess who later becomes the transgendered Shikhandi, ultimately leads to his physical demise.

The story of Bhishma and Amba — as described in the Hindu sacred epic the Mahabharata — began when Bhishma took a vow of celibacy and renounced his right to become king of the Kuru dynasty so his father could marry the woman he loved. As a result, Bhishma’s younger half brother, Vichitravirya, eventually inherited the throne instead.

As soon as Vichitravirya came of age, Bhishma began searching for multiple potential wives for his brother to marry. (It was not uncommon for the kings of ancient India to have more than one wife as that bettered the chances of perpetuating the kingdom).

It just so happened that the king of Kashi had three daughters named Amba, Ambika, and Ambalika, who were ready for marriage. In a tumultuous turn of events, Bhishma arrived at their swayamvara ceremony (an event in which princes competed for a bride), fought off all the other potential suitors, and took the three princesses back to Hastinapura (the Kuru capital) to marry Vichitravirya.

The Kuru dynasty was incredibly prestigious, and so the two younger sisters, Ambika and Ambalika, were delighted to wed Vichitravirya. Amba felt differently, however. Approaching Bhishma, she explained how she and Shalva had already given their hearts to each other, and that the swayamvara was actually pre-arranged for his victory.

After careful consideration, Bhishma arranged for Amba to be escorted to Shalva’s kingdom so she could marry him instead.

When Amba arrived at Shalva’s palace, however, she did not get the reception she had anticipated. Shalva wanted nothing to do with her. He felt humiliated by Bhishma, and as a proud warrior, refused to accept “charity” from him.

Though she begged and pleaded with him, he wouldn’t budge. Heartbroken, Amba eventually gave up and returned to Hastinapura, where she explained to Bhishma what had happened with Shalva, and that she now had no other choice but to marry Vichitravirya.

Bhishma, however — to Amba’s shock — said the option of wedding Vichitravirya was no longer possible because she had already given her heart to another.

Quickly realizing she was running out of options, she then suggested Bhishma marry her. After all, it was he who caused Amba to be in this predicament by taking her. But Bhishma insisted that he could not and would not break his vow of celibacy. Essentially deemed unmarriable, Amba was advised to return to her family.

To understand Bhishma’s reasoning, it’s important to recognize that Vedic civilization was an oral society in which things were not commonly written down, which meant there were no documented transactions that tied people to their word like there are today. As a result, a person’s word — a vow even more so — held moral and legal implications, and informed how society measured one’s integrity, honor, and social status. Bhishma, therefore, was uncompromising in his following of society’s codes of law, and would do so despite whatever consequences ensued.

Of course, actually good moral judgment involves discerning when exceptions to such rules should be made in consideration of a result. While Shalva never achieved this discernment, Bhishma was a great personality who sincerely wanted to do what was right. He thus later adopted a more pragmatic philosophy, but not before angering Amba.

Honest, sincere, and having acted only out of love, Amba had done nothing wrong, yet was cast aside as damaged goods. Reflecting on all that had happened, she was incensed at both men, but concluded that Bhishma was the ultimate cause of her ruined future. If he had never taken her, she would be a happily married queen.

So instead of returning to her family home, she entered the forest and began performing severe austerities to attain the power she needed for revenge. Eventually gaining the favor of the god Shiva, she asked him to give her the ability to kill Bhishma. Granting Amba her wish, Shiva told her that in her next life she would indeed play a part in Bhishma’s death. Determined to fulfill her goal as soon as possible, Amba immediately killed herself.

There are multiple versions of the next part of the story. In some accounts, Amba is born as a daughter to the king Drupada. Told by Shiva that she would eventually be transformed into a man, Drupada names her Shikhandi and raises her as a boy. In this version, a powerful being living in the forest does, in fact, transform her into a man. In other accounts, Shikhandi is born a male, but grows up transgender because Shiva gave her the ability to remember her past life.

Either way, as Shiva promised, Shikhandi does get the opportunity to be the cause of Bhishma’s death towards the end of the Mahabharata during the war of Kurukshetra, and the issue of his gender plays a significant role.

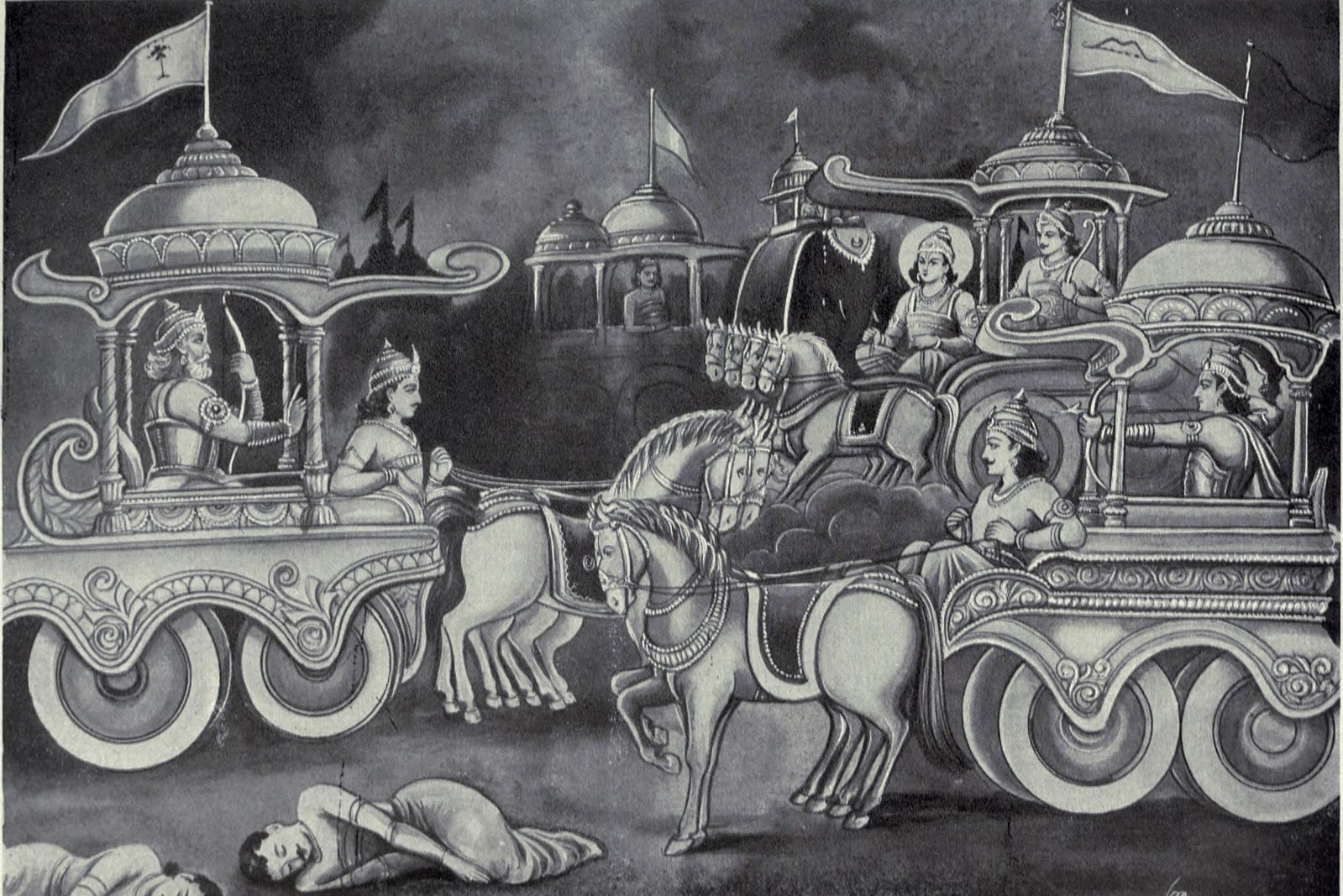

The Kurukshetra war, which lasted 18 days, is the climax of the Mahabharata, and is centered around a struggle for power between two groups of cousins known as the Pandavas and the Kauravas. Though Bhishma knew the Pandavas were incredibly pious and that the world would be a better place with them as rulers, he was politically obligated to the Kauravas, and thus felt compelled by morality to fight against the very people he preferred to fight for.

Though he wanted the Pandavas to win, he knew no one would be able to defeat him in battle. The Pandavas knew this too, and so on the eve of the ninth night of the war — fighting would stop every evening and resume the next day — they approached Bhishma and asked him how they could possibly defeat him. Taking the opportunity, Bhishma revealed that as a warrior, he would never, under any circumstances, fight a woman.

Aware of Shikhandi’s past life as Amba, the next day the Pandavas mounted an attack on Bhishma with Shikhandi leading the charge, followed closely by Arjuna, the most skilled fighter of the Pandavas. Refusing to engage Shikhandi in battle, Bhishma became vulnerable, which allowed Arjuna to take him down with a volley of arrows.

With Bhishma — the commander of the Kuru army — defeated, the Pandavas went on to win the war. And Shikhandi, whose gender was never an issue societally speaking, became remembered as a significant character who played a major part in overcoming the Kauravas.

Today, many discriminate against people like Shikhandi, including Hindus. But true Hinduism means promoting love and respect based on equality of the soul, regardless of a person’s gender, race, or sexual orientation.

Hinduism thus has a history that is inclusive of all types of people and the pivotal roles they have played in India’s most beloved sacred stories.