50 years ago the international community stood silent while millions of Bengali Hindus were systematically slaughtered. Today, we can still speak up for them.

March 26, 1971 was the day that Bangladesh officially declared independence from Pakistan.

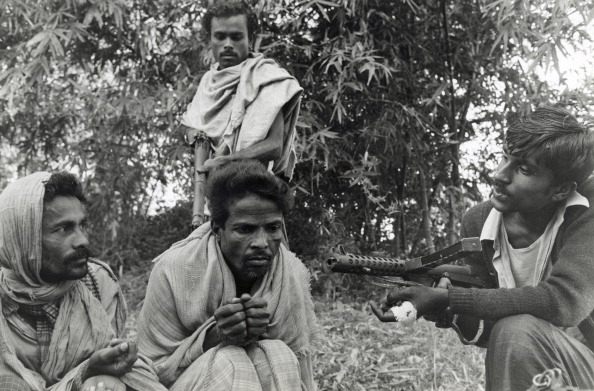

In anticipation of this event, on March 25, 1971, the Pakistan military began a 10-month genocide against the ethnic Bengali and Hindu religious communities, the violence intended to prevent Bangladesh’s secession from Pakistan.

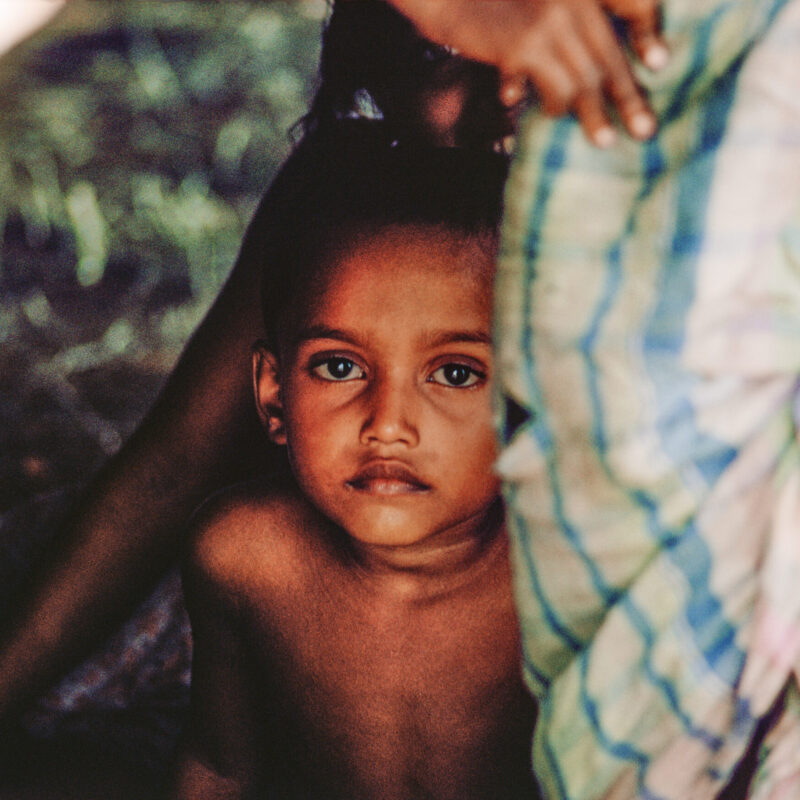

It was ultimately unsuccessful: On December 16, 1971, Bangladesh achieved independence from Pakistan. In the process, some 10 million Bengalis were forced to flee to India as refugees, 3 million people were killed, some 200,000–400,000 women and girls raped— a majority of whom were Hindu.

These events, both Bangladeshi independence and the genocide, affected much of the Indian subcontinent. It involved Pakistan, from which Bangladesh seceded, and whose military carried out the systematic rape, killing, bombing, and mass violence against Bengalis and Hindus. It involved India, which provided safe haven to millions of Bangladeshi refugees, and whose military intervention and 13-day war with Pakistan ultimately led to Bangladesh’s success. Most importantly, it involved Bangladesh, whose Liberation War to liberate itself from Pakistan coincided with Pakistan’s genocide targeting primarily Bengalis and Hindus.

The international community was largely silent on the violence, but there were voices of reason that spoke out

One strong voice of reason was that of the late Senator Edward M. Kennedy of the US. Senator Kennedy visited Bengali Hindu refugees in India, drafted a Senate report on the issue, and secured millions in relief aid for Bangladesh. Each of these actions was monumental for the Bengali Hindu survivors of the genocide. In the Senate report “Crisis in South Asia,” Kennedy details the violence against Hindus and the United States complicity in that violence.

Hardest hit have been members of the Hindu community who have been robbed of their lands and shops systematically slaughtered, and, in some places, painted with yellow patches marked “H”. All of this has been officially sanctioned, ordered and implemented under martial law from Islamabad. America’s heavy support of Islamabad is nothing short of complicity in the human and political tragedy of East Bengal.

The United Nations’ silence was startling considering the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. The convention states that acts of killing, bodily harm, and other forms of violence “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group” constitutes genocide.

Pakistan signed the genocide convention in 1948 and committed the Bengali Hindu genocide in March of 1971.

John Salzberg, then a representative to the United Nations for the International Commission of Jurists, argues in a 1973 article that the United Nations never deliberately considered the violence which singled out “Hindus, members and sympathizers of the Awami League, and students and faculty of the universities.” Salzburg argues that the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination was a clear avenue for UN intervention which was never utilized.

Hannibal Travis, a law professor at Florida International University, reflects on the UN response to genocide since 1945, finding that racial and religious bias has created a double standard in what was considered a genocide, preventing UN intervention. Among a list of genocides neglected by the UN— such as the thousands who died in the chemical attack in Halabja, Iraq and the up to four million Ibos who were killed or starved in Nigeria— he lists the Bengali Hindu genocide: “In 1971, US State Department official Blood cabled Washington about a “genocide” of Hindus and darker-skinned Pakistani Bengalis by lighter-skinned Arab, Pathan, and Punjabi Pakistanis.” The response, he notes, from then-president Nixon was cavalier at best. The response from the UN was nil.

It’s time for the international community to finally stand up for Bengali Hindus

The international community must affirm the 1971 Bengali Hindu genocide now. After 50 years, this affirmation of the genocide is long overdue. We need to acknowledge the 1971 Bengali Hindu genocide to show that we stand against genocidal violence now and in the future.

The United Nations should now pass a resolution affirming the 1971 Bengali Hindu genocide as a first step in a long overdue response. Speaking against the genocide now makes a statement that genocide against all groups is unacceptable and will face consequences from the UN and the international community at large. Affirming this genocide will help to bring solace to the individuals and families affected, and ultimately serve to create space for more meaningful action now and in the future.

The legacy of 1971 is felt in the continued ethnic cleansing of Hindus in Bangladesh today, whose population has dramatically declined. US foreign policy must address religious extremism and protect minorities in Bangladesh, who face continued violence and persecution, often by those same groups that collaborated with the Pakistani army in 1971.