George Harrison’s plan in June of 1971 was relatively straightforward.

After the release of his wildly successful triple album All Things Must Pass, which remained comfortably at the number one spot of charts worldwide, he was to take a break from his own recording projects to help Ravi Shankar Pandit complete the soundtrack to the documentary film Raga.

When he arrived at Ravi’s Los Angeles’ home, however, he found the Indian musician’s mind, rather than primed and focused for work, to be somewhere else entirely.

At that time, East Pakistan (formerly East Bengal) and West Pakistan were in the midst of war, one that began when an overwhelming majority of East Pakistan’s population — after enduring decades of economic, political, cultural, and linguistic repressions from West Pakistan’s ruling elite — called for the region to become an independent nation known as Bangladesh.

Vehemently opposed to a divide in the Islamic community, Islamist organizations, in conjunction with West Pakistani soldiers, responded by launching Operation Searchlight — what came to be known as one of the worst genocides in modern history.

Millions of Bengali civilians were killed (Hindus were especially targeted), millions more fled to refugee camps in India with little hope of surviving starvation and disease, and hundreds of thousands of women were raped.

As a Bengali himself, whose family members were among those fleeing to India, Ravi was deeply distressed. Wanting to plan a benefit concert that he hoped could raise awareness as well as up to $25,000 in aid for the refugees, he turned to George for help.

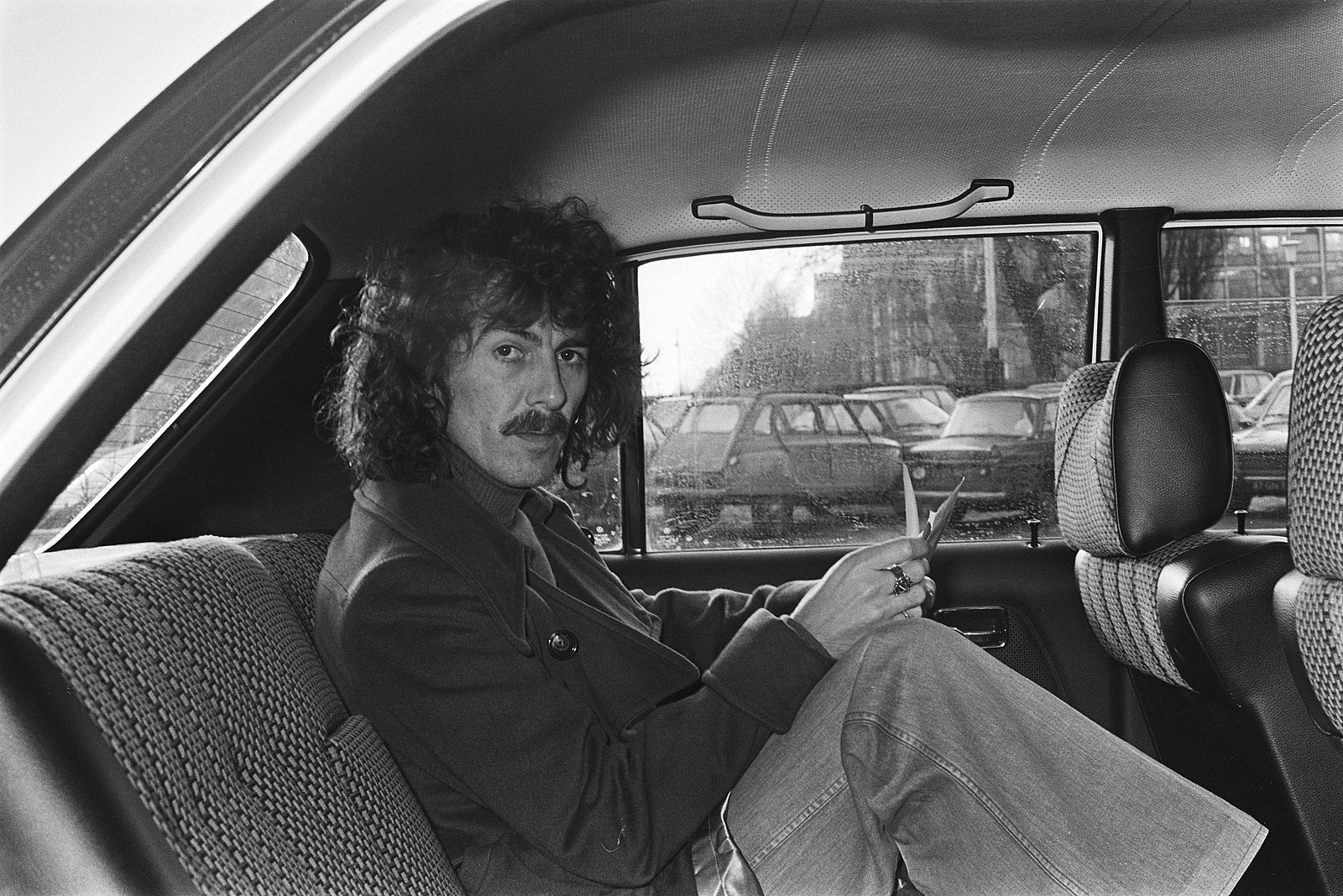

Though an incredibly prominent entertainer, George was not a fan of being in the spotlight. Even as a member of the Beatles — perhaps the most popular band of all time — he much preferred to be the guy in the background playing guitar than the one singing upfront. The idea of being the focal point of a benefit concert, thus, was far outside of his zone of comfort.

But Ravi was no ordinary friend. During the first half of the 1960s, George had the opportunity to meet celebrities of all levels — be they actors, actresses, presidents, kings, queens, or businessmen. By the time he was 22, he had done everything he felt was worth doing, and nothing, as he put it, gave him “a buzz” anymore.

He was looking for something more — hoping to meet someone who really impressed him that was beyond just being a famous celebrity. That’s when Ravi entered his life.

George began taking sitar lessons from the Indian musician shortly after they met at a mutual friend’s home. During these lessons, Ravi taught George more than just the technical aspects of how to play notes and bend strings; he showed him that music could be a gateway to something much deeper.

In Raga Mala: the Autobiography of Ravi Shankar, Ravi said he told George, “There is more to it than exciting the senses of the listeners with virtuosity and loud crash-bang effects. My goal has always been to take the audience along with me deep inside, as in meditation, to feel the sweet pain of trying to reach out to the Supreme, to bring tears to the eyes, and to feel totally peaceful and cleansed.”

With the Beatles, George felt he had climbed to the top of the material wall. Ravi was the first to help him see that there was so much more on the other side, sparking George’s life-long spiritual journey — one that included studying transcendental meditation under Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and later bhakti yoga under A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness.

Like Ravi, Prabhupada encouraged George to use his abilities for the spiritual upliftment of the world. George responded by producing the hit single My Sweet Lord, a devotional ballad to God that ended with the singing of the sacred Sanskrit mantra Hare Krishna.

Even with the single selling more than 30,000 copies a day, the financial success of the song paled in comparison to the deep fulfillment he felt from producing work that nourished his spiritual aspirations. He owed much of this fulfillment to Ravi, who was more than a music teacher to him, but a spiritual mentor and father.

So despite his apprehensions in regard to being in the spotlight, George swiftly agreed to help his friend, but thought they could do better than $25,000. If they turned the concert into a film and album, he knew they could raise far more money and awareness than Ravi originally hoped for.

Setting aside Raga, he spent the next month and a half making calls to some of the world’s biggest rock artists, convincing them to alter any plans they already had for the purpose of coming together — without any pay — to use their talents for a worthy cause.

Ringo Starr was in the middle of working on a film. Eric Clapton was in the throes of battling a heroin addiction. And Bob Dylan had practically become a recluse since a motorcycle accident in 1966.

But they all showed up for this gig.

Other notable musicians, including Billy Preston, Leon Russell, Klaus Voormann, and the band Badfinger also rallied to George’s call. In a matter of weeks, the ex-Beatle had assembled a 24-piece band.

On August 1, 1971, George — smartly dressed in a white suit with an Om sign stitched to the lapel, and the Hare Krishna mantra embroidered on the collar and cuffs — took the stage with his friends at Madison Square Garden, where they played an afternoon and evening set to over 40,000 people.

Besides singing a number of tunes from All Things Must Pass for the first time in front of a live audience, he also performed his newly written song Bangla Desh, the lyrics of which pleaded for the public to lend a hand in relieving the suffering of the refugees.

The concert raised about $243,000 in ticket sales with the film and record sales grossing about $14 million, as the concert record went on to win a Grammy for Album of the Year.

Unfortunately, because the organizers had not applied for tax exempt status, most of the money got tied up in an Internal Revenue Service escrow account. The Los Angeles Times later reported that it took until 1985 before $12 million had been sent to Bangladesh for relief.

But the concert made the Bangladesh refugee plight known to the world in a single night. It was the first ever charity rock concert, creating a framework for future benefit concerts like Live Aid and Farm Aid, and sales of the CDs and DVDs of the event continues to generate money for the George Harrison Fund for UNICEF, which provides lifesaving assistance to children in Bangladesh, as well as many other countries around the globe.

George may have been viewed as the “quiet Beatle” to many, but his spiritual and humanitarian efforts had a resounding effect that still impacts the world today.