One of my most existential moments was soon after a lesson on Hinduism in middle school.

The lesson had mostly consisted of the caste hierarchy, with emphasis on the plight of “untouchables” in India, and the ways in which ritual purity was used as a means to separate people. I distinctly remember feeling confused and unsettled. I thought my mom and dad had taught me a lot about Hinduism through their own stories, taking me to Sunday school, and through beloved Amar Chitra Kathas, but I had never heard about this system, which sounded so discriminatory.

I started to think about my times in India: why the people who worked at our home there were careful never to touch my grandmother; why she had strict rules about who was allowed in the kitchen.

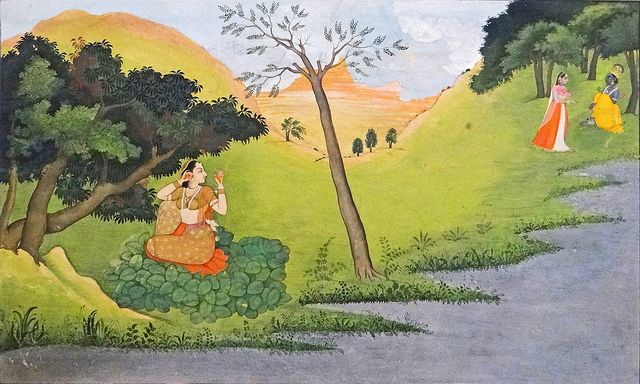

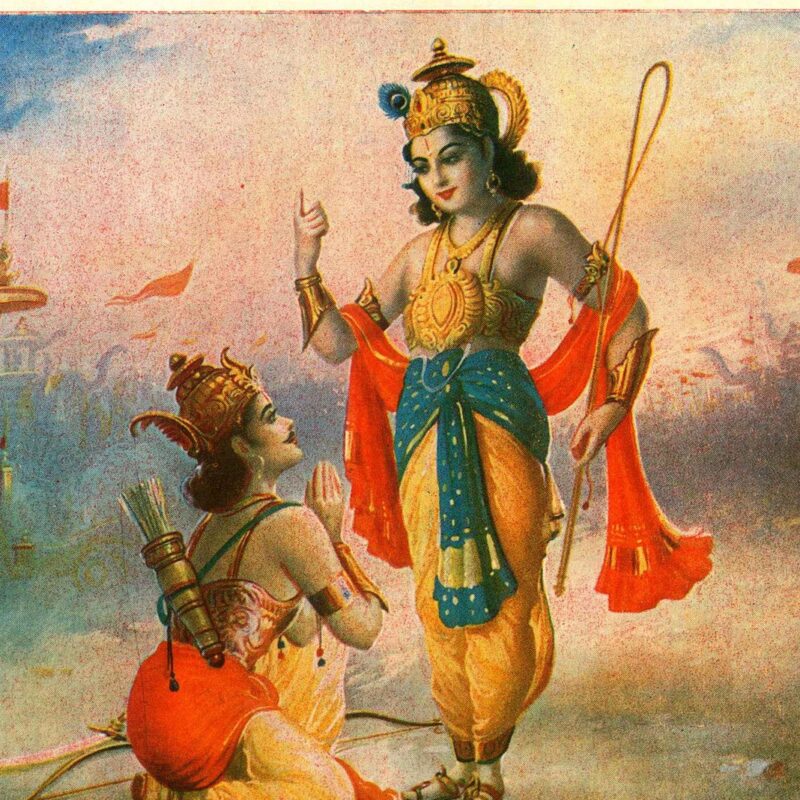

I thought about the Mahabharat episodes I had been watching and wondered if this explained why everyone seemed to be so mean to Karna, a man raised by a charioteer despite being the son of a god.

My discomfort grew as I reflected. Was my religion built to encourage us to discriminate against people who were lower on this hierarchy?

It was a dark moment for me, but those lessons from my parents started to break through. Yes, I had never seen this pyramid before, but that didn’t mean I didn’t know Hinduism. I knew what was important, which every Hindu person, scripture, and teaching I had encountered myself had emphasized —that we are all divine, that dharma compels us to do good, and that our karma creates our circumstances.

How could a message of discrimination make sense in a religion that went so far to say that all people are divine, whether they’re even Hindu or not? There were things that didn’t make sense to me at times, and sometimes the messages I got contradicted each other, but this was what always felt consistent. Everything and everyone is divine, and part of the ultimate spiritual goal was being able to see that.

I was comfortable dismissing the idea of the hierarchy as a Hindu construct on my own, but I was now hyper aware that discrimination was a reality. I had seen enough to realize that whatever the scripture said, people didn’t all treat each other with the recognition that we were all divine. The more I observed with open eyes, the more I saw that everyone was striving to be better than those around them, and that those who had climbed a rung were quick to use their privilege to assert their superiority in some way.

The image of my grandma recoiling from being touched came to mind quickly, as well as several other things I had seen in India and among Hindus, but other images came flooding to mind quickly after: the smug look on a friend’s face giving food to a homeless person, watching a woman carve a large path around a colored man in a hoodie, the stories on the news about Enron executives stealing millions of dollars from those who couldn’t have protected themselves. I even saw it in myself, in my disdain for “lazy” group members when I took the lead on a project, my choice on where to sit on the bus.

When I started taking psychology classes, my observations became even darker. We learned about the Stanford Prison experiment and what people had done to each other under the loosest labels of power and prisoner. I became certain that there’s a part within us as humans that feels the most secure when we can assert power or superiority in some way. I started reading history as an endless quest for people and groups of people to assert their own power.

These ruminations on human nature and what we as a species were capable of, were discouraging for me, but there was certainly a silver lining. If this journey had me wondering if Hinduism was an tool of oppression, it ended with me realizing that it was actually the only tool I had to find some light. As I looked, I found that far from encouraging the dark part within me, I could use my faith to rise above this pettiness, to push myself to truly see divinity around me, and become a better, more compassionate, person — as so many before me had.

Doubts about who we are and what we should believe are not so quickly put away, however. I had another moment of deep questioning as an adult, when I started hearing stories every day about the terrible abuses women in India were facing — the rapes, the acid attacks, the general culture of harassment. I felt like I had been blind for so long and was suddenly made aware again of how dark humans were. I tried to disconfirm what I was being shown, when I asked my cousins if this new picture was their reality or if the media was overblowing something. They confirmed that they made a great deal of sacrifices and adjustments to their lives because they didn’t feel safe outside of the walls of their homes. I couldn’t blow it off. I had to rethink everything again.

While I knew my country, the USA wasn’t perfect, I began to wonder if India had a unique problem, and began fearing the role that Hinduism, the dominant faith had. I had long felt empowered by the centrality of Goddesses in Hinduism and what I had taken in as a respect for female energy. I had to pause now and reassess all these stories. What was I really supposed to make of Sita’s treatment, of everything Draupadi was put through? It was gut wrenching to think through what had once brought me courage as a weakness.

However faith again broke through. The men in Sita and Draupadi’s lives acted as, well, men living in patriarchal societies have the privilege to act. They acted as human beings surrounded by other human beings looking for power acted. They were disenfranchising at times, cruel at others. But as I looked back, I saw that the texts called that out. They didn’t justify those actions. The same texts did encourage us to see and understand how Sita and Draupadi responded to their trials and tribulations. They showed us that they were strong, that they overcame, that we should not only respect them, but aim to embody their character. These were the stories of humans, though. In the divine, we had stories of Durga, who was created by being given the best weapons of all the Devas, to accomplish what the Gods could not. We had Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth that we all wanted to invite into our homes. We had Saraswati, who every person with ambition and a thirst for knowledge calls upon in moments of crises. We had the idea that without Shakti, without feminine energy, the world is incomplete.

Most of the world has always operated under patriarchy and it has been a struggle to move towards equality everywhere. It is distressing to see how women’s rights are abused so often, so widely. It is uplifting to be able to rely on faith to rise above this, and to be empowered towards enacting change.

We’re all human. Religion makes us more than that, not less.