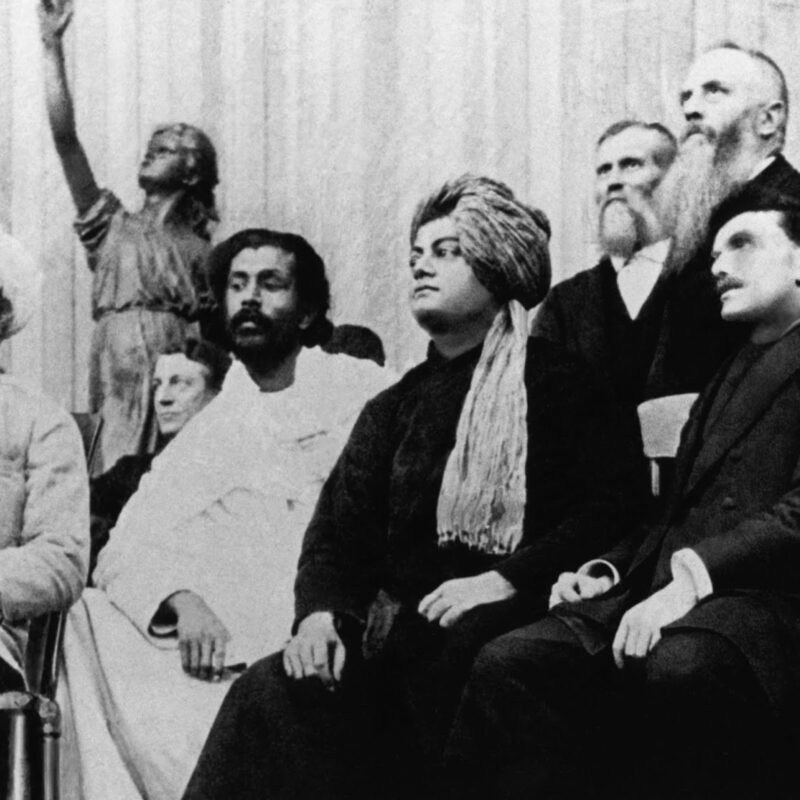

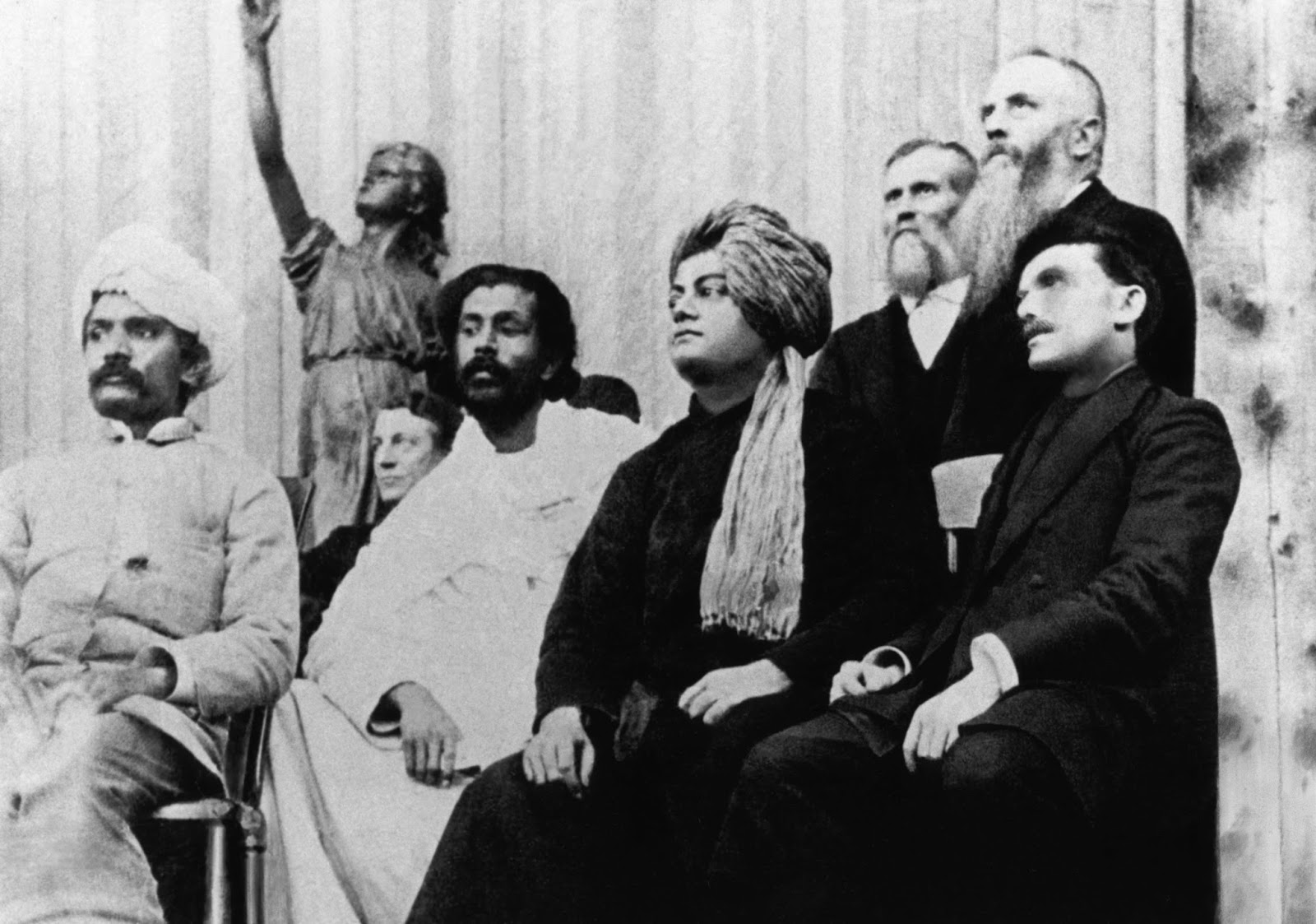

Next month will mark the 120th anniversary of Swami Vivekananda’s landmark speech at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago, but a key aspect of his American trip continues to be overlooked for its significance in the ongoing struggle for civil rights and human dignity.

Vivekananda’s visit to the United States, in which he became the most prominent Hindu ambassador to set foot on American soil, is remembered for introducing a generation of Americans to Hinduism and then-colonized India. He paved the way for other Hindu leaders to come to the United States in the 20th century, giving the religion a lasting presence in the country at a time when Indians and others of South Asian descent were unable to come here due to laws such as the Emergency Quota Act, which restricted non-European immigration.

But Vivekananda never received enough credit for his meditations on racial injustice in the United States. During his stay in America, he spent time in both the East Coast and Midwest, noticing first hand the de facto segregation that kept whites and blacks apart. On a train ride through Tennessee, for example, Vivekananda refused to sit in the “Whites Only” train car, choosing instead to sit in the car reserved for African-Americans in order to highlight the injustice of segregation. He understood the paradox of his position as a privileged visitor (of color) from a colonized country in a land where millions of citizens were denied basic rights. He was also deeply troubled by the contradictions within a country where Christianity was preached, but not practiced, particularly in following simple truths of equality and tolerance of others. That is why, in a subtle challenge to his Christian counterparts on living their principles in a multi-racial society, Vivekananda noted in his speech, “I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance.” In the same speech, the monk condemned bigotry of all kinds, perhaps drawing a connection between religious intolerance and racial discrimination.

When Vivekananda spoke in 1897 about the condition of blacks following the abolition of slavery, he concluded that African-Americans were “a hundred times worse off than today than they were before the abolition. Today they are the property of nobody.” Vivekananda was noting that Blacks in the South had no legal standing and were literally a population without citizenship — they were neither free nor enslaved. Sadly, his views on the struggle of African-Americans during the Jim Crow era — and his empathy for them — have been grossly misinterpreted by numerous writers and intellectuals, particularly in India, over the years

But prominent African-American intellectuals and activists, namely W.E.B. Du Bois, understood exactly what the monk meant. Du Bois never met Vivekananda (who died in 1902 at the age of 39), but greatly appreciated the deep sense of empathy that Hindu leaders felt for the condition of African-Americans. In his correspondence with Hindu leader and Indian anti-colonial icon Lala Lajpat Rai, Du Bois wrote that Hindus in India and African-Americans had a common destiny, one that had been forcefully interrupted by colonial rule and Jim Crow, respectively. Du Bois’s interpretation of Vivekananda and his correspondences with the likes of Rai and Rabindranath Tagore formed the basis of his worldview at the end of the Harlem Renaissance era and in the years leading up to World War II. Du Bois’ relationship with these leaders even inspired his 1927 novel, Dark Princess, a long forgotten utopian work in which a Hindu princess marries an African-American protagonist in an effort to bring the so-called darker races together against Christian imperialism and exploitative capitalism.

The cooperation between Hindus and African-Americans has been an overlooked aspect of American (and Indian) history, though scholars such as Nico Slate, Gerald Horne, David Levering Lewis and Bill Mullen, to name a few, have tried to articulate those deep bonds, perhaps to remind us that communication and cooperation among communities of color is by no means a recent phenomenon (Author’s note: I wrote about this too in my biography of Du Bois and Robeson).

Vivekananda’s empathy and his pleas for tolerance among different races and religions was not lost upon those who used his words as a rallying call for social justice. Coretta Scott King — deeply aware of the influence of Hindu ethos on her husband — remarked that Vivekananda had given “the most definitive statement of religious tolerance and interfaith unity in history.” Perhaps in a time of deep racial polarization and other forms of intolerance in this country, we can draw upon the philosophy of Swami Vivekananda in our quest for equality and social justice.

This article was originally published on Huffington Post.