Either in social studies and history, or tangentially during classes on other subjects, teachers may teach about Hindu and/or Indian peoples, history, beliefs, customs, religions, etc. Given that only a few periods or a portion of a class may be devoted to the topic, one would expect that teachers and the teaching materials treat Hindu traditions and Indian history accurately and in the same manner as other world religions and civilizations.

Unfortunately, that’s not the case.

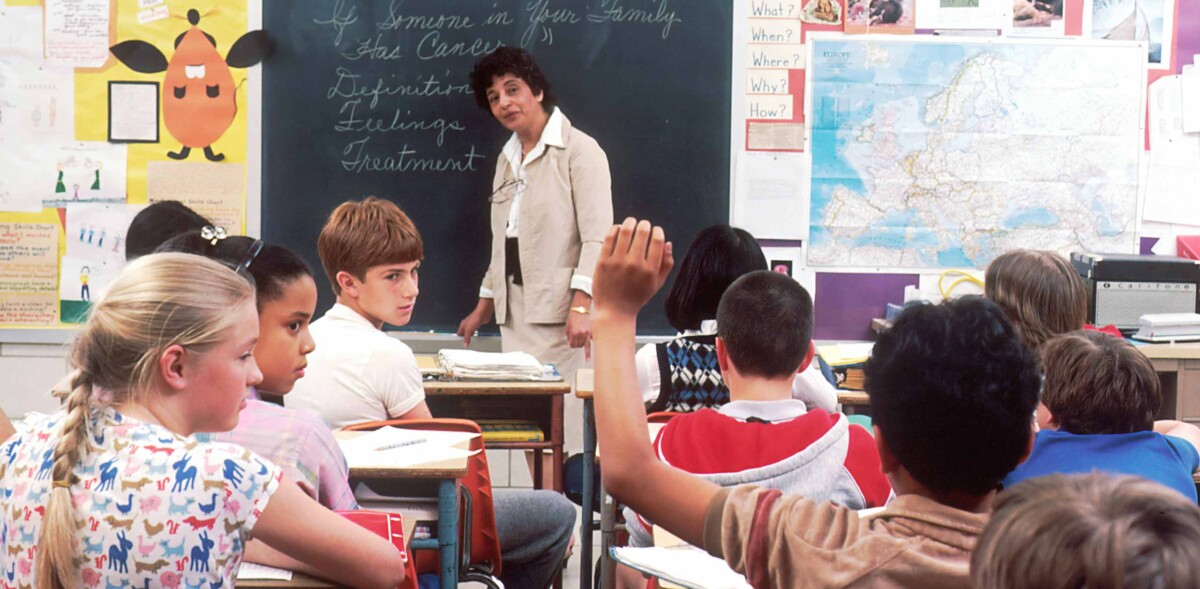

Textbooks, readings, assignments, or even guest speakers currently used by a majority of middle and high school teachers are full of inaccuracies, omissions, and disproportionate focus on social issues when it comes to the Hindu Dharma traditions (Hinduism) and the Indian Subcontinent.

This guide is intended to help you review content in your child’s textbook or content presented during class on these subjects and prepare a short summary of issues for discussion with your child’s teacher or school administrator, where the content is found to be problematic.

Public vs Private School

Why this matters

Public Schools

Public schools are tuition free and funded by federal (up to 9% of the total), state and local governments – known as public funding. Proportions of the source of public funds differ per state.

Types of public schools

Magnet

Focuses on a specific area like science or the arts

Virtual/Online

This type of school exists online.

Charter

Publicly funded, tuition-free schools. Permitted in 45 states and D.C. They are independent of public school districts, and operate autonomously, on the condition of good results, as funding is only provided for between 3-5 years depending on the charter agreed with the state government.

Private Schools

These schools do not receive any public funds. They derive their funds from private donors, investors, and student tuition. Due to this, the school’s own board has greater control of its curricula.

Types of private schools

Boarding

Requires boarding and lodging on the campus. There is a greater focus on extracurricular activities that inculcate values desired by the school board into the students through the staff and faculty of the school.

Language Immersion

A school whose primary or secondary language of instruction and extracurricular activities are those other than the English Language.

Montessori

These schools focus on a student’s individual interests, where teachers often teach the same batch of students for three years. Learning goals are achieved through teacher-directed activities and readings, and less through formal instruction.

Private Special Education

Private schools that has a special focus on students with special needs, be they physical or cognitive.

Religious

Independent private schools that are affiliated with an association governed by members of a specific religious tradition.

Parochial

Independent private school that is directly tied to a local church or religious institution.

Reggio Emilia

Like Montessori schools, this type of private school uses an ethos determined by the North American Reggio Emilia Association which prioritizes the development and monitoring of a student’s emotional and behavioral development in tandem with their educational progress.

Waldorf

Similar to Montessori schools, this type of private school uses an ethos that focuses on the physical and intellectual development of the student. In this method, a teacher stays with the same batch of students for five to seven years.

How Hindu Dharma is taught and addressing potential negative effects

Who Determines How the Hindu Dharma Traditions and the Indian Subcontinent Are Taught?

The method in which a teacher introduces their class to the Hindu Dharma traditions and the Indian Subcontinent is not directed by any federal curricular standard. The US does not have an enforceable national curriculum. Your state’s Department of Education has an Education Code that applies broadly to all public schools and the subtypes in the state. The individual public school districts generally set the curricula for all public schools in their respective jurisdiction, but the individual school boards and departments have leeway in how they interpret the guidelines and codes.

Parents/legal guardians have the ability to raise issues of concern pertaining to the method of instruction, teaching materials/textbooks, assignments/exercises, or even guest speakers who talk about Hindu Dharma traditions and the Indian Subcontinent broadly. In the case of public schools, the most efficacious methods start at the individual school level, and can be escalated to the district level if the issue is seen as pervasive (such as a common textbook that is inaccurate), or even the state level if the state Department of Education has such objectionable materials listed for use. Public school districts and state boards also utilize public curriculum adoption processes which include opportunities for parents and community members to review and provide comments on proposed curriculum and individual textbooks prior to their use in the classroom.

Private school boards generally address the concerns of parents/legal guardians – and particularly donors – as the funding comes directly from them. However, if there is a specific mission of the private school that does not prioritize accurate representation of Hindu Dharma traditions or the Indian Subcontinent, they are less likely to mandate change. Instead of leaving the school, the student’s parents/legal guardians can instead escalate concerns to the association or education body to which the private school belongs, or reach out to HAF, to explore the paths for possible resolution.

What about Anti-Hindu/Hinduphobic Harassment or Discrimination Experienced By My Child Stemming From How the Hindu Dharma Traditions or the Indian Subcontinent Are Taught?

A study the Hindu American Foundation conducted in 2015 found that student experience of faith-based bullying was tightly correlated to their perception of the focus on caste in their Hinduism curriculum, potentially mediated by a perception that their religion was being taught negatively.

If your child has faced harassment, bullying, or discrimination stemming from how the Hindu Dharma traditions or the Indian Subcontinent were taught, we’ve prepared a guide to protections for students under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (accessed here), and will assist with any advice needed including and beyond this guide. Compliance with US Department of Education policies such as Title VI is a condition for schools that receive public funding.

What to Look For In Textbooks,Teaching Materials, and Class Presentations on Hindu Dharma traditions (Hinduism) and the Indian Subcontinent

Proportionality and Impartiality

Given the time limits for teaching about religion in American classrooms, are Hindu Dharma traditions given similar class-time as Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, etc.? While there may be a tendency to spend more time on Abrahamic religions rather than the Dharmic traditions given American demographics and history, any classes on social studies, history, or humanities should provide equal time and quality of instruction and materials to the Hindu Dharmic traditions as given to the Abrahamic religions.

Does the teaching material discuss Hindu Dharma traditions and associated civilizations and cultures along similar themes as other world religions or do they focus only on negative or inaccurate stereotypes? Are the images and captions used in sections pertaining to Hindu Dharma traditions or the Indian subcontinent representative of Hindus and Indians or are they exoticized? Given the extensive scholarship which exists around the ancient origins of Hindu Dharma traditions and their differences, does the material concoct a monolithic explanation of the concepts or does the material honor the diversity?

Below you will find more concrete explanations on common errors that lead to disparities in how Hindu Dharma traditions and the Indian subcontinent are taught.

Federal Law

Public schools must comply with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015, which reaffirms the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 on section 8534, and is a condition of being allocated federal funding. Private schools tend to align with the ESSA as well. The ESEA states that these schools must ensure that discrimination does not take place:

SEC. 8534. [20 U.S.C. 7914] CIVIL RIGHTS.

- IN GENERAL.—Nothing in this Act shall be construed to permit discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex (except as otherwise permitted under title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972), national origin, or disability in any program funded under this Act.

Though reassuring, it is very generalized and whether disparities in curricula would come under the law’s purview is open to interpretation. Nevertheless, at the federal level, the most important resource is the Office of Civil Rights in the US Department of Education, which may assess instances where schools have contributed to discriminatory environments for students either at school or online under Title VI. They do not investigate discrimination due to religion (which would fall under the purview of the Department of Justice), but they do investigate discrimination of a group with shared ancestry or ethnic characteristics, which includes Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, and Sikh students, whether or not the student belongs to said group.

State Law

Of greater consequence than federal law, state law can be a useful benchmark when assessing whether the instruction or instructional materials your child is receiving is discriminatory due to their inaccuracies or pejorative approaches. Do the methods of instruction, class material, assignments, or readings adhere to your state’s laws?

Here is a distillation of California state law, as an example:

- California State Law, particularly Education Code Sections 60044 (a), (b)*, prohibit instructional materials that reflect adversely upon individuals based on various factors, including religion. The California Legislature recognized the vital role of instructional materials in the formation of a child’s attitudes and beliefs when it adopted Education Code sections 60040 through 60044, 60048, and 60200. In summary, their purpose is: to project the cultural diversity of society, instill in each child a sense of pride in his or her heritage, develop a feeling of self-worth related to equality of opportunity, eradicate the roots of prejudice, and thereby encourage the optimal individual development of each student. No classroom material that reflects adversely upon a person’s race, religion, ancestry, or national origin.

Common Textbook Errors About Hindu Dharma Traditions and the Indian Subcontinent

If your child’s textbook or teaching materials contain any of the following common errors, or a guest speaker presents problematic information, we’ve provided background to assist you in drafting bullet points for your letter to the teacher/administrator.

COMMON ERROR

Racialized theories about the origins of ancient Indian people have long been discarded by historians based on archeological, linguistic, genetic, and migration evidence. Āryan is not a racial identity but a cultural one and Āryan culture is one of hundreds that contributed to the development of Indic civilizations and the Hindu Dharma traditions.

WHY IT’S INACCURATE?

The philosophies and practices of Hindu Dharma traditions developed initially in South and West Asia, however, they proliferated throughout Central Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia well before the Middle Ages. The so-called Āryan Invasion Theory, which posited that a light-skinned Aryan race traveling from the West invaded the Subcontinent and displaced the existing population of dark-skinned indigenous people and subsequently developed and enforced a race-based caste system, has long been discarded by scholars.

Āryan means noble. Linguistic, archaeological, and archaeo-genetic evidence confirm that Āryan is the name of a shared, dynamic, and fluid culture which was adopted by numerous clan-confederations or tribes from different ethnic and even racial backgrounds (the Hittite, Mittani nobles, and Iranians all identified as Āryan; Buddha called his teachings Āryan, positing new values for those who are Āryan). These various clan-confederations or tribes came from all over Asia. Yet, the Āryan culture was just one among hundreds of other distinct cultures practiced by clan-confederations and individual clans. It is either in awareness of one another or directly working together that the rich philosophies and practices seen in the Hindu Dharma traditions developed. Singling Āryans out as the root of Hindu Dharma traditions and using the Indus Valley Civilization as the only alternative clan-confederation or tribe is not only inaccurate; it denies the hundreds of clan-confederations or tribes their part in the evolution of Hindu Dharma traditions.

COMMOM ERROR

The portrayal of the whole of Indian society as ascribing to a rigid, hierarchical and oppressive caste system or Hindus as oppressors is racist, reductive, and inaccurate. Europeans conceived of this theory, which included the idea that this system was created and enforced by a small and oppressive Hindu priestly class of the false religions of the Indian Subcontinent with seemingly little to no opposition from the masses for millennia. The reality is that Indian society, past and present, is like any other society on the planet, where social structures, identities, and dynamics are complex and fluid.

WHY IT’S INACCURATE? PROPORTIONALITY**

The “caste system” is not a religiously mandated social model in Hindu history – its present existence is due to the British Empire-era laws enacted across the British Raj and enshrined in colonial studies and legislation.

From available textual evidence, the vast majority of ancient Indian republics and kingdoms were self-governed, and as such, no singular, uniform social or legal model existed across all the clans, clan confederations (tribes), as well as kingdoms and republics (both types were formed by tribal nations). Indeed, some (not all) kingdoms may have posited social and legal structures which sought to govern status, behaviors, and relations on the basis of one’s, occupation, class, or gender. These kingdoms would have also had hereditary professional guilds that practiced endogamy similar to other civilizations across the world (feudal system of Europe, land-ownership rights in Arabia, etc.).

Today most people would consider aspects of any structure which limits individual autonomy, choice, or freedom as unfair and oppressive. Even in ancient times, a vocal majority decried such structures as being motivated by greed and contributing to social divisions and lack of social and individual mobility. They either foregrounded ancient egalitarian models or devised new ones appropriate to the times. In all cases, Hindu spiritual leaders were active participants in guiding and supporting alternative social models which were believed to contribute to the wellbeing of the community as well as the individual.

To present the caste system as if all of ancient India, and more importantly, all Hindus either practiced or practice it today, is thus historically and factually incorrect.

Many textbooks and teaching materials also state that efforts to counter the so-called “Hindu caste system” started with the Buddha, Mahavira, or the Sikh Gurus, or was a reason for uncoerced conversion of Hindus to Islam and Christianity. These claims are also historically inaccurate and ignore or underplay the fact that Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs (and Christians and Muslims in the Indian Subcontinent, for that matter) have “caste” or community-based identities with associated oral histories and traditions, as well as perceived differences which can and have led to identity-based rivalries or discrimination.

Some textbooks and teaching materials further suggest that condemnation and redress of the “Hindu caste system” and associated discrimination was championed only after the Indian Independence Movement by the first officials of Independent India: this too has no basis in history.

Quite alarmingly, we have had reports of dozens of classes wherein students were separated into four groups and discriminate against each other as they were told castes did. Stereotypes about caste and a supposed Hindu caste system are the basis of much stigmatization, harassment, and bullying of Hindu American schoolchildren. To have erroneous or reductive material in American school textbooks and teacher-assigned exercises further reinforces both false and racist stereotypes and minimizes or ignores the majority of Hindu teachings which promote individual and community flourishing (varṇa), and efforts to outright invalidate social divisions, social immobility, and marginalization.

COMMON ERROR

Teaching saṃsāra as simply suffering or reincarnation; karma as fatalism or allowable actions determined by a “caste system;” and dharma as duty or a set of laws determined by a “caste system” is reductive to the point of inaccuracy. Defining the jīvātman or ātman as the soul and Brahman as God is also inaccurate.

WHY IT’S INACCURATE?

These are the concepts that are shared across the variety of pan-regional Hindu Dharma traditions.

- Saṃsāra: All Dharmic traditions, observed that like the natural world, living beings too undergo repetitive cycles of ups and downs. Many of these elicit emotional reactions in addition to physical ones. Managing life in and freedom from saṃsāra is the focal point of Hindu Dharma traditions, not pleasing or fearing God.

- Karma: Though Saṃsāra is the reality of things; it does not mean one cannot change how it affects them. Empowered action comes from deeper understanding, rational thinking, and reasonable decision-making. All of this is entailed in the teaching of Karma. Predestination, fatalism, or determinism are not universally accepted parts of the teachings on Karma.

- Dharma: That which sustains. This is the holistic philosophy and practice that allows a human to progress. An approximate, yet solid, translation is a spiritual tradition. Dharma is a term that is also used with a variety of meanings in different contexts – such as the essential propensity of a thing, ethical values, etc.

- Sādhanā: A well-planned and reasoned regimen of spiritual practice that builds up the capacity for a person to adopt philosophies and practices that are conducive to better physical, emotional, mental, intellectual, and spiritual wellbeing. These spiritual practices are the empowered actions (Karma) that lead to Mokṣa.

- Mokṣa: Also known as nirvāṇa or mukti, refers to the state of being free from the effects of the cycles of saṃsāra. At a basic level, mokṣa indicates the ability of a person to not be unhinged by the natural cycles of this multiverse and of life. However, at the existential level, it refers to the innate ability of every human being to free themselves from their habitual, negative cycles of thoughts, actions, and feelings, and attain a state of equanimity and thereby perpetual tranquility or bliss.

- Jīvātman/ātman: the body is the vehicle for the jīvātman/ātman, the embodied Self. What exactly the Self is varies according to a given Hindu Dharma Tradition’s philosophy. However, in essence, the teaching is the principle that our essential nature is eternal and is separate to the body, mind, and intellect. The body, mind, and intellect are within our control to manage or improve with sadhana, intention, and guidance. When the body dies, the mind, and intellect also cease to function, but the essential nature of the Self persists.

- Jagat: This means the whole of existence. As the Dharma traditions teach that there are multiple universes, Jagat therefore means the multiverse. They also teach that the multiverse is without beginning or end, and that it simply cycles through manifestation, maintenance, and dissolution eternally. That it has no beginning means there cannot be a creator. This is one crucial difference of the role of theism in Hindu Dharma Traditions as opposed to other world religions.

- Karuṇā: Given that variety is natural, the Dharmas spend much time rationalizing the fact that compassion is the true and essential nature of a human being, even though it is obscured by layers of past memories, tendencies, desires, aspirations, etc.

COMMON ERROR

Hinduism cannot be reduced to polytheistic or monotheistic. In fact, centering belief in God(s) over-simplifies and erases important distinctions amongst the different Hindu Dharma traditions.

WHY IT’S INACCURATE?

Hindus are not primarily concerned with belief in God(s). This concern is Abrahamic, as belief in God is the chief criteria of being a member of those religions.

Hindus do not have to believe in God in order to be Hindu. So, giving primary focus to God/Gods in Hindu Dharma traditions is not representative. Moreover, statements about Hindus practicing polytheism are a pejorative, and derived from the specific histories of Abrahamic traditions and the traditions that surrounded them, which are not the same as those of Ancient India.

- Ignoring the difference between the Supreme Being (Īśvara, theist being) and Ultimate Reality (Brahman, non-theist principle). As the Jagat exists eternally, there is no creator. Ultimate Reality refers to the sum-total of the multiverse, the jīvātman or ātman, and potential energies, times, natural laws, etc. (basically, all perceivable and imperceivable existence, and potential existence). The monotheistic Hindu Dharma traditions, however, personify the Ultimate Reality as Īśvara, the Supreme Being. This is intended to make it easier to form a devotional relationship with Īśvara, which in turn allows for an intuition of the Ultimate Reality. The Supreme Being according to Śākta, Śaiva, Vaiṣṇava, Smārta, Kaumāra and other monotheist Hindu Dharma traditions, is the sole focus for meditation or devotional practice. Some traditions favor the concept of Brahman over Īśvara, or Īśvara over Brahman, or see them as synonymous descriptions of the same thing – in essence, it is this flexibility that helps humans throughout their lives.

In some cases, actual palpable help is needed; in others the abstract Ultimate Reality is a good ‘big-picture’ to help zoom out from the issues we are surrounded by and contextualize them in a manageable way.

- Ignoring (Mono-)Theism and Non-Theism. The Supreme Being, although translated by missionaries as God, serves a different function in the Dharmas. For monotheist Hindu Dharma traditions, the Supreme Being is the center of their meditative or devotional practices. The abstract Ultimate Reality is less of a focus for these practitioners, as a relationship with the Eternal is of more consequence to their lives. However, the non-theist Hindu Dharma traditions based on philosophies like Vedānta, Sāṅkhya, Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, etc. are non-theist in that there is no ‘creator’; everything exists eternally in either an expressed form or potential form.

Submission to God or even belief in God as a requirement of being a Hindu is not needed; devotional relationship with the Supreme Being is the personal choice of a Hindu and does not stigmatize or exclude them in one way or the other.

- Saying Hindus worship 33,000,000 gods: Hindu Dharma traditions have observed that there are subtle empowered principles (some traditions teach that they are actual beings) that uplift (Suras/Devas) or delude (Asuras/Rākṣasas) – in addition to all the sentient beings we can empirically observe. These should be accurately translated as Empowered or Illumined Beings. While some traditions see them as metaphorical representations of the subtle things that persuade us, other traditions personify them, and suggest appealing to the Empowered/Illumined Beings for blessings and assistance in life.

COMMON ERROR

Hinduism is not a single religion but a family of distinct traditions, which may share overlap in their espousal of certain core concepts, but differ significantly in their interpretations, teachings, traditions, practices, and history. To teach otherwise is akin to teaching about Christianity without mention of Catholics and Protestants or Islam without mention of Sunni or Shia.

WHY IT’S INACCURATE?

As will be clear, “Hinduism” actually refers to a vast group of pan-regional Monotheist (Śākta, Śaiva, Vaiṣṇava, Smārta, Kaumāram, etc.), pan-regional Non-theist (Cārvāka, old Nyāya, Sāṅkhya, etc.), and regional-ancestral (like Kirat, Sarna, Sanamaha, etc.) Hindu Dharma traditions. They are cognizable. Relegating the regional-ancestral Hindu Dharma Traditions to “folk Hinduism” is an inexcusable inaccuracy that erases numerous indigenous clan-confederations (tribes) from the history of the development of the Hindu Dharma traditions. Given the uniqueness of each of the above-mentioned traditions is greater than Shia and Sunni, Protestant and Catholic, to not see the distinct Hindu Dharma traditions respected and discussed in an equitable manner is at the very least poor scholarship.

COMMON ERROR

Presenting Jainism, Buddhism, or Sikhism as reform movements rejecting the Hindu “caste system” is ahistoric and thoroughly inaccurate.

WHY IT’S INACCURATE?

Scholars of religion in the West were more familiar with European and American Christianity and its history. They thus saw religion in two ways. The first was as the confusing, nonsensical, superstitious, primitive religion that humans either developed through evolution from simpletons to intelligent or as a result of being deluded by the Devil. The second was the arrival of the unique reformer who clarified the mistakes of the former religion bringing sense, hope, true faith and true religion to the superstitious masses. Everyone that rejected this was seen or portrayed as condemnable.

For them, Judaism was a mass of confusion caused by the differing viewpoints of the Rabbis, and Jesus was the one who made the true religion. The duty was to civilize everyone both with knowledge but also with the right religion – which explains what happened to European Pagans, Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire thereafter. Muslim scholars also latched onto this, as the “mess” that was Arabian Paganism, Judaism, and Christianity were corrected by Mohammed and his Islam. These same scholars used these lenses and forced the spiritual traditions of ancient India into these very boxes – searching for reformer characters, and landing on the Buddha, Mahāvīra and the Sikh Gurus. Everything else was the singular, old, primitive, senseless religion which they named Hinduism. The Indian Independence Movement leaders, though Indian, had studied religion from such scholars, and their own understanding of religion in the Indian Subcontinent is colored by these categories, which explains the various issues caused by forcing Dharma traditions into the boxes more fitting for Abrahamic religions.

In fact, Jain Dharma and Buddha Dharma were two among the many Dharma traditions of Ancient India. It is because of the religious scholars and colonial politicians that we see that Buddha Dharma and Jain Dharma are counted as world religions, but the equally autonomous Dharma traditions of Śākta, Śaiva, Vaiṣṇava, Smārta, Kaumāram, etc. are bunched together as ‘cults of Hinduism’. Given that Śāktas are as different to Vaiṣṇavas as Sunni Muslims are to Eastern Orthodox Christians, the classification currently used is absolutely inequitable and, frankly, ahistorical.

Sikh Dharma had its origins in the Sant Movement of the Hindu Devotional Renaissance of the 15-16th centuries. And even after Sri Guru Gobind Singh established the Khalsa in 1699, it wouldn’t be until the politics during the British Empire that a separate Sikh religious identity was forged. Given that the British fought wars with the Sikh Empire, it was thus easy for colonial scholars to count them as a distinct world religion.

An argument could be made that Buddha, Jaina, and Sikh Dharmas all have their own book, a founder, and a central authority. But, that is the case with the vast majority of Śākta, Śaiva, and Vaiṣṇava Dharma traditions also. Therefore, it should be noted that world religions are but one way of viewing the spiritual traditions of Ancient India. If one was to look for an indigenous way of understanding the Jaina, Buddha, and Sikh Dharmas, it would be that these three were each uniquely formed as a Dharma tradition, amongst the other Indic Dharma traditions that existed in Ancient India and Asia more broadly.

It is because the scholarly academy does not study traditions from Asia with the same attention and rigor as it does western religions that these kinds of errors persist. The current understanding forces all the Dharma traditions that are not Jain, Buddhist, or Sikh to be labeled as ‘sects’ of Hinduism. Per the current scholarly understanding, saying that all Dharma traditions were part of a similar cultural and geographical area would be equivalent to saying all of these Dharmas came from Hinduism – which we have demonstrated is factually incorrect. The natural and historical formation and evolution of the Jaina, Buddha, and Sikh Dharma traditions are thus taught not to be seen as one of the numerous Dharma traditions available to the peoples of Ancient Asia, but as totally separate, reactionary, and isolated from their inceptions, which is, again, factually incorrect.

COMMON ERROR

Images and content that convey strangeness or foreignness of Hindus or Indians perpetuates the ugly racism and xenophobia of early Europeans and Americans otherizing India.

WHY IT’S INACCURATE?

For Europeans and Americans during the age of Empire, the Indian Subcontinent was as exotic a place as they could get. They would zero-in on differences and use them to typify Hindus as a whole in the sources they created. The absolutely egregious labels of cow-worshippers, idolaters, blood-sacrifice practitioners, polytheists, superstitions, confusion, blind faith in erroneous theologies, sensual and voluptuous sex-crazed people, socially discriminatory, untouchability, widow burning, etc. all derive from the complexities of British rule and the inability of these early scholars to separate their familiarity with 19th-century Victorican or Puritanical standards of religion from an objective treatment of the realities and histories of Hindus. Are social issues in Christian history, for example the Inquisitions, witch burnings, and kidnap of Indigenous children – all of which are well known to the scholarly academy for their atrocities and millions of humans tortured and murdered – given as much time as social issues focused on when covering Hindu Dharma traditions? Sadly, Hindus today have to spend most of their time speaking about these same misconceptions rather than the core concepts of Hindu Dharma traditions, which leads to a paradoxical reinforcement of these destructive stereotypes about Hindus. The solution to this is to focus on an equitable presentation of Hindu Dharma traditions based on the latest research (rather than relying on summaries that are based on outdated colonial sources).

COMMON ERROR

Claiming that a Hindu’s family name signifies their ‘caste’ in accordance with Hinduism is absolutely unfounded.

WHY IT’S INACCURATE?

Jāti is not ‘caste.’ Jāti are tribes or generalized people groups with some kind of shared distinguishing features, such as origin story, history, worldview, teachings, customs, vocations or occupations, and/or language and dialect, etc.community or clan. Many Hindus come from regions wherein only the first name is used followed by a term that signifies their village, town, region, vocation or spiritual tradition and not any kind of ‘caste.’ Many Hindus feel great attachment to their family names or surnames as it connects them to the land, an oral history, vocation, or tradition of their ancestors. This is common across many global cultures, too.

Hindus in Ancient Indian Mīmāṁsaka (one of the Hindu Dharma traditions) kingdoms, where jāti-based social organization resembling occupational guilds was instituted, could nevertheless exit the jāti of their birth, if they wished, and join another Hindu Dharma tradition (remember, Mīmāṁsaka is only one of them). According to numerous Agama sources, thru ceremonies of empowerment (dīkṣā), these individuals and families were given one of the names of the Supreme Being (Śiva, Vāsudeva, or Śakti) as their family name, and that became their new community identity, beyond the jāti categories. This was then accepted by the broader society in general, and in the few cases of extremely trade-centric kingdoms, these people created new settlements with like-minded families and individuals.

This method of exiting jāti-based societies was stopped by the British Colonizers as they mixed up kula, jāti, religion, presumed purity, occupation, and other locally recognizable social identities and made up the catch-all category of ‘caste’ and institutionalized it. The Hindu method of exiting these occupational jāti has been totally ignored and erased by missionary, colonial, and Indian Marxist scholars, wiping out the historical experiences of the millions of Hindus both in South Asia and, importantly, in the Caribbean, Mauritius, Fiji, etc. All of these people became members of Rāmānandī, Vārkarī, and other Hindu Dharma traditions.

Indeed, members of one jāti may have held perceptions of difference and superiority, and mistreated members of other jāti in ways that were inhumane or unethical. Such perceptions, however, were highly localized, and were informed by a variety of factors ranging from social, economic, political, historical, even religious. That said, members of poorer or deprived jāti also did not simply concede an attributed inferior status claim by others nor simply accept the claimed superiority of others over them. The social standing of a jāti in one region could be very different from a similar or even the same jāti living in another region, and one’s social standing changed by exiting their jāti or if their jāti moved from one region to another.

Perpetuating the stereotype that all Hindu surnames indicate a caste identity is ahistoric and denies agency to those who retain family names to connect to their ancestors.

COMMON ERROR

Throughout the world, women have not historically served as prominent spiritual leaders, except in the most rare of cases. However, students are being taught that only women in Hinduism are subordinated and subjugated. This kind of projection is both ahistorical, unfactual, and inequitable.

WHY IT’S INACCURATE?

Hindu women – since records began in the Veda – have been spiritual leaders, teachers, and served in roles that most societies in the world reserved for men. The entire, and perhaps most ancient monotheist pan-regional Hindu Dharma is that of Śākta Dharma where the Supreme is personified as female, and the spiritual leaders are female. Menstruation is not seen as unclean as it is in some Abrahamic religions and in the Mīmāṃsaka/Smārta Hindu Dharma tradition. Women celebrate the first menstruation of the young women; the peak of female capacity is not as housewives but as women fulfilling their dreams. The most spiritual women are not stereotyped as celibate, modest, virgins. Most are very open about relationships and bodily autonomy (ie. sexual activity), or are fierce protectors, as they embody the full spectrum of femininity, not just a ‘chaste’ motherly role.

Additionally, Hindu Dharma traditions were very comfortable with the existence of people who were born with male or female biological bodies but did not have sole attraction for people of the opposite sex. Indeed, 43 different sexual orientations and gender identities were noted and grouped as Tṛtīyā Prakṛti or Third Nature. Even if not labeled as LGBTQIA+, the vast majority of Hindu Dharma traditions openly accepted people whether they had sex or relationships with people of the same or different genders. Prominent stories tell of numerous same- and trans-sexual relationships and encounters between figures of great spiritual importance to Hindus. Even the trade-driven Mīmāṃsaka societies, which had a lot to say about relationships given that inheritance and taxation depended on a heteronormative family, made sure that single people of the Third Nature communities were cared for by the state.

Some Hindu Dharma traditions, particularly those formed during the Islamic or Christian colonization of Asia, do have heteronormative expectations and roles for their members. However, they are just a few in number and in no way can be seen to represent the whole of the Hindu Dharma traditions, most of whom are very open about the fact that nature is not only binary. As Nepal was never colonized, Hindus there never criminalized same-sex activity. The Mughal Empire instituted Sharia Law which criminalized same- and trans-sexual activity, and the British criminalized it formally under the Penal Code section 377, applying it in all their colonies as well. India finally overturned this British law in 2018, allowing freeing Hindus from colonial shackles. In time, the Colonial attitudes that linger in this regard will likewise be addressed.

Other Controversial Topics

Did another controversial topic come up in your child’s class that conflates political issues with Hindu Dharmas? For example, here are some topics that are being taught incorrectly as if they are part of Hindu “doctrine”:

- Hindus are inherently Islamophobic

- All Hindus instigated violence during partition against Muslims to create a solely Hindu country

- Hindus want to banish or subjugate all Muslims in Kashmir

- Hindus overstate the Bangladeshi Hindu genocide as a way of whitewashing their own genocidal tendencies

- Hindus especially hate and wish to kill Dalits, Christians, and Muslims.

If so, check out these additional resources to help craft a letter specifically addressing: