In an ironic way, being born and raised in the United States allowed me to engage in the most “Hindu” of practices in a way my father, born and raised in our spiritual homeland India, never did: I questioned everything. And I’ll give my father a lot of credit. He recognized this behavior as an opportunity to deepen my faith in a profound way and always encouraged me to do the work to find the answers. I’m grateful that he laid the foundation for me to find myself in the room where Acharya Vijay Satnarine was able to help me reflect on the questions, “Why do we call ourselves Hindu?” “Why do we call ourselves practitioners of Hinduism?”

The etymology of the word Hindu goes all the way back to the 8th century BCE and the Sindhu river, which demarcated the land on side between the Persians (who began the legacy of calling the Sindu the Hindu) and the people I call my ancestors.

These people, referred simply to as the Hindus (akin perhaps to calling those who today practice the Abrahamic faiths, Jordan River Valleyists). They believed many diverse things, but what could be seen across the region was a respect for these differences, and a pluralistic ethos that managed to allow everyone to coexist in spite of the human tendency to tribalism.

Tribes could choose to fuse, affiliate, or remain separate. No conversion policies or taxes for differences in practice were observed, and even as tribes inevitably synthesized, space remained to practice the individual traditions of a person’s family, clan, and tribe. In the land of this ethos, the dharmas developed — spiritual traditions focused on the philosophy and practice of means to manage or be free from the inevitable, repetitive ups and downs of life. Humans were humans, violent at times and united in others, but culture was a means of rising above and not a vessel to justify territorial ambitions.

In the Jordan River Valley, we saw the human draw for tribalism play out in ways that were both similar and different, and emerge as the Abrahamic traditions, which came to define the word religion itself: the vow/promise/oath to follow the laws of a god.

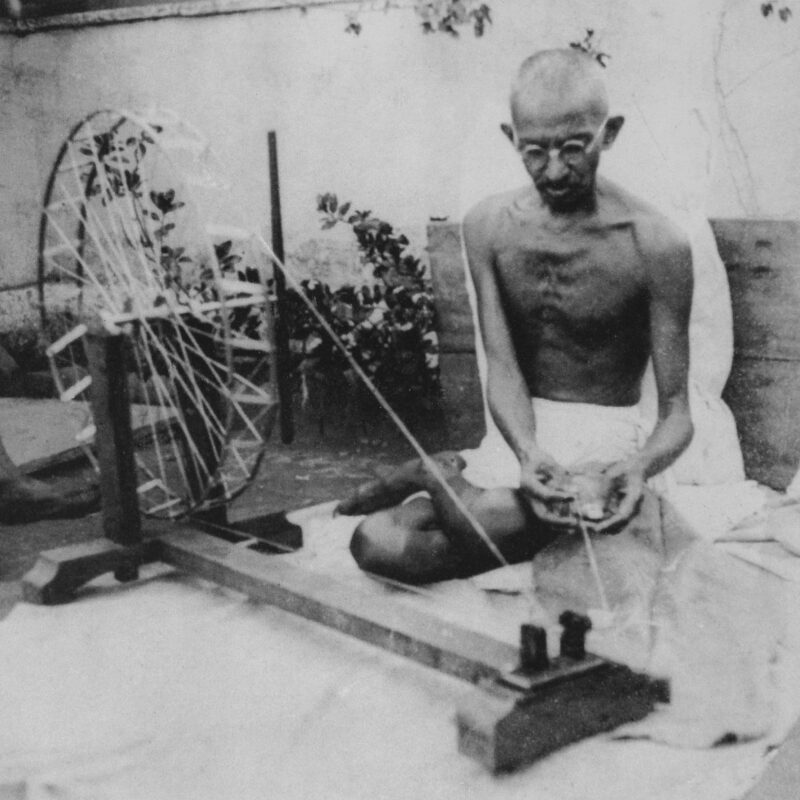

When the Mughals chronicled their wave of colonizing the “Hindu” region, they recognized the thousands of nuances and millions of differences in the strains of thought, belief, practice etc. When the British colonized the region, they took the step of condensing all they didn’t understand to be one singular thing: Hinduism. Those who “practiced” what they saw as this heathenism, were Hindu. Hence the definition changed. And while dharma isn’t synonymous with religion, we must reflect on the weight that this word has on the entire planet. Can we find a modern nation state that isn’t founded by, founded as a reaction to, or incentivized by colonial thought and policy?

In understanding the colonial ensnarement of the words Hindu and Hinduism, it’s not surprising that the first question posed is, “Well is there another way you’d then like to be described/labeled/understood?”

And of course, there are many who would respond to that with a plethora of terms: Shaivite, Vedantist, Sanatan Dharmi, etc. that capture the essence of what they believe, think, and practice.

However, these terms have the limitation, in that the ignorance of the West stops them from hearing these words and seeing the connection to the larger shared ethos of the spiritual homeland.

Those who practice what we’re referring to as Hinduism may contradict each other on every single possible dimension, theism, diet, rituals, thoughts about the afterlife, marriage, patriarchy, and on and on and on. However, there is something that binds them together: their connection to the land of Hindus.

This is true whether they live in a small town in midwestern USA with no attachment to India, and even if they hold no DNA to connect them physically to the subcontinent.

The ethos that developed the land is pervasive, seek truth. Respect the seeking of truth. Ask questions. This is what Hindus have done. This is what Hindus are.

In one of the DEI trainings that has stayed with me the longest, the speaker was asked a similar question to the one we’re unpacking here: how do you feel about the label disabled, and the desire by many to use other terms?

Her response was profound. She shared that the world we live in disables her in many ways, and makes many actions and areas inaccessible. As long as that is true, she shared, she would use the term that communicated her challenges. She articulated a dream of a world where improved access rendered the word and reflection on it entirely unnecessary.

I think that as we take in the flaws and complexities of the words Hindu and Hinduism to define us, we can also acknowledge the protection they provide us.

We live in a world where many use the world religion to describe the way that people relate to the universe, beyond the textbook definition of “belief in a god”, and struggle to find the world to explain a person’s quest to understand how to cope with the nature of the universe. We live in a world where we do understand the profound relationship one has with their faith, and in one where pretty much every government in the world has weighed in on how to protect the practice of facilitating that deep connection with the universe.

While I believe it’s undeniable that Hinduism doesn’t fit into the box of “religion” in the neat way that the religions that have determined the definition of the word do, the protection offered by the box is not one that this world allows us to be without.

Ergo, for today, my name is Kavita, and I am a Sanatani Hindu who practices Hinduism.