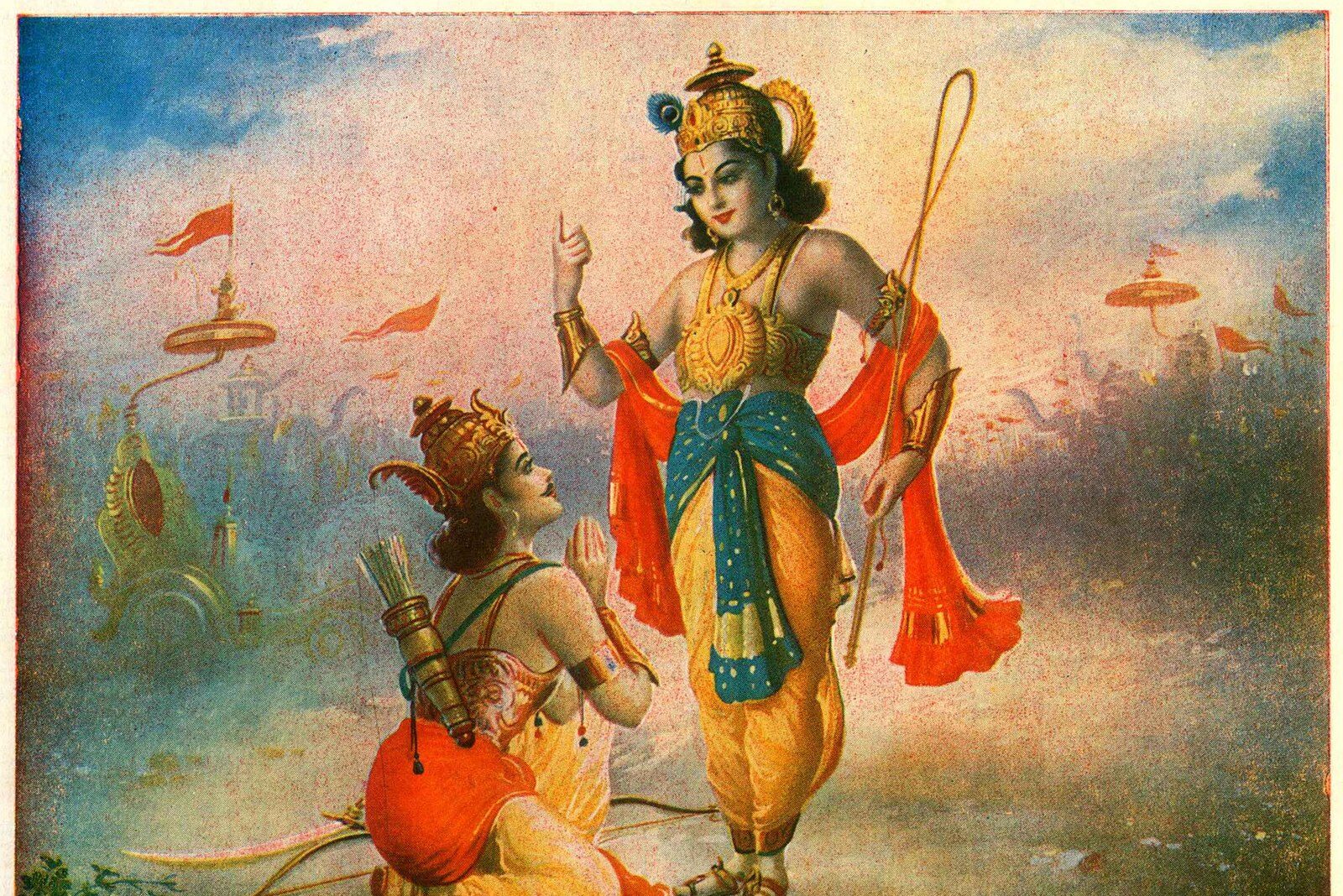

Krishna, a form of the Divine, imparts timeless wisdom to Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra

Beyond the boundaries of religion

Humanity is filled with seekers, searching for answers that can impart the light of hope and purpose amidst darkened times of struggle and confusion. Averse to the various scriptures of the world, feeling they carry far too much religious baggage for their comfort, however, many avoid them, longing for something free of any sort of doctrinal framework.

Sometimes, of course, such aversion is warranted, especially considering all of the harm and exploitation that has taken place throughout history in the name of religion. But sometimes it isn’t. Sometimes, appearances can be deceiving. And if you’re one among the scripturally reluctant still looking for guidance on the path for meaning, we’re here to tell you about a text we think you need to give a chance, despite its religious packaging. In fact, we think everyone should, regardless of who they are, or where they come from.

Hear us out.

The Bhagavad Gita might appear like a sectarian work, meant only for those willing to buy into the “Hindu religion,” yet nothing could be further from the truth. Actually, before it became the religious identifier it is today, the term Hindu had no such connotation.

Derived from the Sanskrit Sindhu, which was the local name for the Indus River that flows through the Northwestern part of India, it was originally a linguistic morph of the Persians, who used it to denote the region and inhabitants beyond the waterway. While it gradually evolved into a social and religious significator, catching on in popular and practical use, it has never represented one single system of beliefs.

The underlying concepts that inform much of Hindu spirituality, described as timeless wisdom realized by sages through meditative states in the distant past, aren’t part of a static doctrine or creed, but make up a dynamic tapestry of teachings, aimed at helping practitioners of all backgrounds navigate the volatile condition of the world in pursuit of Divine transcendence. Hence pluralistic by nature, Hinduism houses a diverse range of traditions, approaching Divinity from a wide variety of perspectives, offering insight through an immense catalog of spiritual texts.

Summarizing, probably better than any of them, the philosophical foundation upon which most of these perspectives are built, the Gita, therefore, isn’t a dogmatic scripture dictating rigid life commands. It’s a practical guide, providing universal principles that can help anyone of any context understand and overcome life’s greatest challenges.

Hard to believe? Just keep reading.

An open “Bhagavad Gita,” its pages filled with wisdom, offering guidance for every seeker

Timeless teachings for a changing world

Part of a larger composition called the Mahabharata (the world’s longest epic), which narrates a dynastic struggle between two groups of cousins vying for the crown of a ruling capital, the Gita is a 700-verse dialogue that takes place at the edge of war, when the virtuous Pandava brothers are forced to take up arms if they want to win a kingdom that was stolen from them.

Though they are fully equipped to defeat the enemy and secure what is rightfully theirs, the opposing army is filled with their family and friends, so Arjuna, the most skilled warrior among them, becomes plagued by doubts. Torn by the prospect of slaying so many of his loved ones, he turns to his cousin Krishna, who has been a loyal adviser and friend to them all, and questions if the throne is really worth the cost. Motivated by envy, their cousins might be in the wrong, but surely the crime doesn’t justify fratricidal bloodshed. Thus paralyzed by grief, he casts his weapons aside, falls to the ground, and spirals into darkness.

Seeing him in such a state, Krishna, who eventually reveals himself to be a form of the Divine, proceeds to revive and enlighten Arjuna, launching into a discourse that covers, in detail, five core existential topics. Categorized as follows, they are:

- Atma (Self): Every living being, according to the Gita, is a spirit soul encased in a physical body.

- Prakrti (Material World): While the soul is immortal and unchanging by nature, material energy, which constitutes everything that makes up the physical world around us — including the bodies we inhabit — is impermanent and in a constant state of transformation, shifting from one form to the next.

- Karma (Activities): Forgetful of our real nature, we perform one activity after another, hoping to achieve happiness by gratifying the senses of the body. Because, however, we’re not the temporary body, this happiness is fleeting, and ultimately unfulfilling. True and lasting happiness comes only when we address the spiritual yearnings of the soul, and as spirit is opposite to matter, spiritual happiness comes not from self-indulgence, but self control aimed at cultivating an unwavering disposition of unconditional love and connection. Likened to a kind of rehabilitation center meant to help lost souls understand this truth, the universe operates under the law of karma, by which every thought and action has a corresponding reaction. Experiencing the good and bad results of our deeds, we learn — if we choose to pay attention — how our acts affect those and the world around us. Thereby increasing our sense of universal empathy and brotherhood, we can rise above the recurring waves of our karma, and perform only spiritual acts, all in pursuit of spiritual perfection.

- Kala (Time): Plagued by innumerable varieties of lust, anger, greed, envy, pride, and illusion, it goes without saying that spiritual perfection is a daunting goal to attain in one lifetime. Most people, as a matter of fact, don’t. Propelled by the wheel of unstoppable time, souls, therefore, play out their karma in a cycle of reincarnation known as samsara, until, after many lives of spiritual practice, finally break free, achieving liberation.

Ishvara (God): What exists beyond the inexorable wheel of time, and what is the proposed spiritual practice we can perform to reach said existence? This, naturally, is where God, or Divinity comes in. Like a blazing fire of eternity, knowledge, and unlimited bliss, the Divine is the transcendent source from which all of us originate, and all of us find ultimate union. As separated sparks of this fire, we are in a kind of extinguished state, but by performing yoga (meaning “to unite” in Sanskrit), of which there are four types, we can reestablish our lost connection, rekindling the pure and selfless light of our true selves.

A pilgrim walking along a path, symboizing a journey of spiritual discovery and purpose

A unique path for all

Compared to different branches that help us scale the tree of enlightenment, each yoga type lifts us to the Divine by engaging our major energies in a particular spiritual discipline.

Karma yoga, for example, is about dovetailing our working energy in performing selfless service to others. Raja yoga (the kind of yoga most people think of in the West) is about directing our vital energy in physical postures, breathing exercises, and meditative concentrations. Jnana yoga is about employing our mental energy in studying spiritual subject matters. And bhakti yoga is about using our loving energy in acts of devotion to all.

As Krishna describes the four yogas, it becomes apparent they aren’t mutually exclusive, but require aspects of each other, overlapping and blending in multifarious ways to progressively draw one’s whole being in tow with the inclinations of the practitioner. All of us, therefore, depending on our physical, mental, and emotional makeup, have a unique spiritual path, each of which comes with a particular dharma, or set of sacred duties we should follow if we are to stay the course.

Arjuna’s dharma, Krishna declares, is to fight, no matter what the outcome. As the heart best serves itself and the body by discharging its function of pumping blood, Arjuna best serves himself and the world by executing his function as a warrior in the face of battle. To truly follow yoga, or the selfless path of spirituality, we must learn to selflessly carry out our duties, even when they cause personal unhappiness or distress, and leave the rest — which is ultimately out of our hands — to the wisdom of a higher order.

Uplifted and inspired by the full import of this message, Arjuna concludes the Gita by gathering his senses and preparing for battle, determined to fulfill his dharmic role, while we as the readers are left realizing we too can do the same.

We may not be literal warriors on the field of battle, but we are warriors on the battlefield of life, and like Arjuna, the obstacles we face aren’t always black and white. They’re complex, baffling, painful, and often have us on our knees, reeling in darkness and confusion. But by applying the philosophical blueprint of the Gita, we can find our way out of any crisis, illuminated and empowered.

And if you’re still having doubts, remember, the proof is in the pudding, and many of the world’s greatest thinkers can vouch.

Aldous Huxley called it “the most important psychological and philosophical work the East has produced.” Albert Einstein said when he read it, everything else seemed “superfluous.” And Mahatma Gandhi exclaimed, “When doubts haunt me, when disappointments stare me in the face, and I see not one ray of hope on the horizon, I turn to The Bhagavad Gita and find a verse to comfort me; and immediately, I begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming sorrow.”

So what are you waiting for? Get your hands on a Gita, open its pages, and delve into the magic of its timeless power.

You won’t regret it.

Oh, and in case you’re not sure where to start, considering the many translations that exist, don’t worry, we’ve got some recommendations. Check it out!

Bhagavad Gita: The Beloved Lord’s Secret Love Song

The Gita: For Children

Gita For Children (A Teaching Tool For Elders)