The following is a guest article by Clifford Smith, Washington Project Director at Middle East Forum.

The worshippers at the Hazratbal Shrine a centuries-old holy site in Indian Kashmir, took no notice of me as I walked I sat down on the floor among thousands of others. This mosque contains a holy relic, a piece of hair belonging the Prophet Mohammad, making it the holiest Muslim structure in the Kashmir valley. To me, this was a moving experience of a new culture. To the locals, it seemed to be Tuesday.

As I left, I realized that this experience was a far cry from what India’s critics are suggesting who claim that the Indian state is conspiring to stop Kashmiri Muslims from worshipping.

This sort of revelation happened a lot during my trip, which became an exercise in separating the fact from propaganda.

India zoomed past China earlier this year to become the world’s most populous country. And according to a study released in July by Goldman Sachs, India is forecasted to be the largest economy in the world by 2075. Moreover, it is a democratic and pluralistic country, increasingly seen as a bulwark against an expanding China.

Americans will need to understand India’s history and politics, including its most intractable conflict, and how it affects their internal and external politics, without the filters of overt propaganda from those who wish India ill, if it is to make the most out of the relationship.

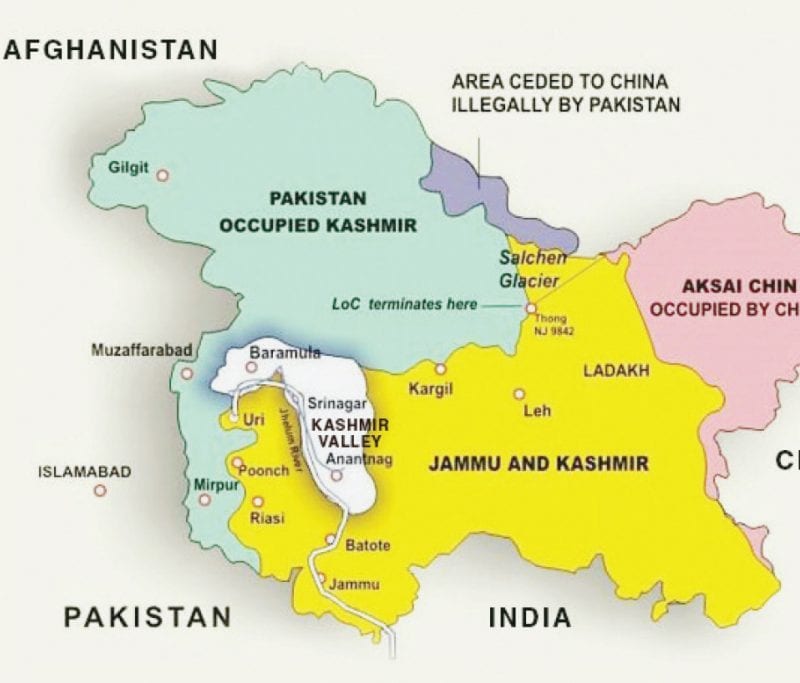

The conflict over Kashmir, a Muslim-majority region in the thick of Himalayan mountains that separates India, Pakistan, and China, dates back to the partition of the subcontinent in 1947. But events in recent years, particularly the 2019 Pulwama terrorist attack, perpetrated by Pakistani-based terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed, and the subsequent revocation of Article 370 of the Indian constitution, an initially temporary measure which gave Indian-controlled Kashmir a semi-autonomous status, have supercharged the issue.

Months ago, Pakistan publicly attacked India for holding G20 forum events on the Indian side of the border in Kashmir, accusing India of “illegal attempts” to change demography in Kashmir. Some US-based Islamist groups, with deep ties to Pakistani politics, began actively pushing narratives in the US on the issue that were at odds with reality.

One does not need to know all that much about Kashmir to realize that “genocide” against Kashmiri Muslims was not happening, nor that wildly implausible figures alleging mass gang rapes by the Indian military, were suspect. But US-based Islamist groups such as the Islamic Circle of North America, associated with South Asia’s Jamaat-e-Islami movement, were pushing this narrative.

It is ironic that a chapter of Jamaat-e-Islami was making such accusations, given that the organization is perhaps best known for being among the chief perpetrators of the Bengali genocide in 1971.

There are certainly fair-minded critiques of the Indian government, but accusations of genocide aren’t that.

Former Indian Minister of External Affairs, Salman Khurshid, a Muslim, once said, “If religion is used as a carving knife to redesign politics, virtually the whole world will have to ready itself for the chisel.” He’s correct.

When I landed I Srinagar, a few days before visiting the Hazratbal Mosque, heavily armed central police were common sights, a reminder that India’s central government remained heavily involved in Kashmir.

Yet Kashmiris did not seem tense as a result. At the airport, a woman wearing a dark niqab asked me for help getting her bag. Pleased to oblige, I was surprised she seemed so comfortable with an obviously Western man.

The dress of Muslim women in Kashmir varied wildly. A few wore niqabs or burkas, most others wore hijabs, sometimes with colorful, elaborate patterns, common in the region. A small minority didn’t wear a head covering. The men’s dress ranged from very traditional, like what you might see in Afghanistan, to being indistinguishable from Americans or Europeans.

Sadly, poverty is still present. As soon as I left the airport, I saw handful of women begging in the streets. India’s rapid economic rise is undeniable, having raised roughly 300 million out of poverty between 2009-19, and evidence of new investment in Kashmir, was everywhere, but there’s still a long ways to go.

The hotel I stayed at had several police outposts. Kids engaged in horseplay nearby constantly. Both ignored the other.

The hotel staff spoke excellent English, as most educated Indians do. I asked if there was a traditional Kashmiri greeting I should use. “As-salamu alaykum,” I was told, with a slightly bewildered look. I smiled, “Even I know that one.”

Kashmir is perhaps most famous for the houseboats and shikaras on Dal Lake, a large lake surrounded huge Himalayan foothills. There were many tourists there from all over India, Hindu and Muslim alike, and a smattering of Americans, Europeans, Chinese and others as well, visiting the lake and gardens that surround it.

But there’s a difference between acceptance of tourists, and the acceptance of permanent “outsiders”.

A group of returning Kashmiri Pandits recently moved back to the valley, working as teachers. Pandits are Hindus that were driven out of Kashmir in 1990 by armed terrorist groups such as Hizbul Mujahideen, the armed wing of Jamaat-e-Islami. One Hindu woman, Girija Tickoo, was gang raped and sawed in half while still alive. More brutal tactics would be difficult to imagine. 400,000 Pandits are believed to have left as a result, and prior to 2019 few returned.

The Pandits spoke proudly of thousands of years of Hindu presence in the valley. They blamed Jamaat-e-Islami’s radical ideology for the indoctrination of children. While the Government has encouraged Hindus to take teaching jobs, some complained about a lack of sufficient services and security.

Nonetheless, they wanted to use their teaching positions to show Muslim children that Hindus were not their enemies. I asked if Hindu had enough credibility with Muslim families get them believe Hindus can be friends.

“It’s hard. It will take time,” one replied.

Despite this challenge, it occurred to me that these Muslim children were still in school, despite having Hindu teachers.

Before the repeal of Article 370, the ability of non-Kashmiris to enter Kashmiri society was curtailed. But even the few Kashmiri pandits moving in, unquestionably local in any traditional sense, were few. To the degree they were “changing the facts on the ground,” it was to a pre-1990 status quo of having a relatively small Hindu presence in the valley. According to a recent report, only a few thousand Hindus have moved back to Kashmir, which has a population of over 10 million. This is not ethnic cleansing of Muslims, nor massive changes in demographics.

Of course, many Kashmiri Muslims do not object to Hindus. One young Sunni Muslim couple, Yana Mir and Sajid Yousuf Shah, invited me to their house for dinner. They supported the government’s actions, believing it brought more peace and prosperity to the valley. They have no problems with Hindus, and in fact, were in as much danger as the Pandits. They helped to run the website, The Real Kashmir News, which has “a vision to promote positive news from the Kashmir valley,” and lived in a housing complex guarded by police as a result.

There has not been a large scale terrorist attack since Pulwama, and stone-throwing incidents have gone down significantly, but the terrorist attacks remain a major threat and targeted killings threaten Hindus, such as Sanjay Sharma, a security guard who was killed earlier this year, and Muslims that dissent from the separatist line.

Shia Muslims in the valley have long been in a different situation than their Sunni counterparts. Making up about 15%-20% of the region, they fear Sunni theocracy. Javed Beigh, a Shia who is also a local representative from the Shia-heavy Budgam district, told me that Shia had been “at receiving end of Pakistan backed militant organizations,” and that slogans calling Shia Muslims “infidels,” was prominently “Written on walls of the houses of Shia’s by these very separatist militants who are demanding so called ‘independent Kashmir.’”

Beigh explained that “The separatist movement in Kashmir is primarily for establishment of radical Sunni Muslim Caliphate on lines of what ISIS has done in the Middle East or what Taliban did in Afghanistan.”

On the other hand, Beigh pointed to increased government funds for important projects in his district that he helped bring, and suggested further development would improve things further. “Unfortunately views of the Shia Muslim community both in Kashmir Valley and rest of India are never heard.” He’s working to change that.

Another Shia activist I met, Munazir Mehdi, described the government as a “bully,” and said he wanted to moderate the government’s behavior. He did express sympathy concerning what happened to the Kashmiri Pandits in 1990 but said that the Indian Government had not considered the fact that most Muslims in the Kashmir Valley acknowledge the atrocities and did not want them repeated and hoped to take steps toward reconciliation but argued it had not been reciprocated.

This activist’s father was the most senior Shia cleric in the Valley who is involved philanthropy and social engagement intending to create more social cohesion. Mehdi proudly showed me photos of his father meeting various prominent Shias, including Sheik Hassan Nasrallah, the Secretary-General of Hezbollah, and prominent Iranians. However, he stressed that he did not view Iran as a solution to the Kashmir issue, deeming them “unhelpful,” believing it should be solved bilaterally.

Unhelpful as it may be, Iranian influence in the Shia parts of Kashmir was obvious. In Shia dominated areas, propaganda featuring Iranian regime leaders are commonplace.

The views of normal Kashmiris are ultimately perhaps even more important than that of elites and activists. One local Kashmiri Muslim, a waiter, simply wanted to tell an outsider his views.

He said things were difficult before 2019, due to militancy, which left fewer jobs and fear among the locals. But that things were “very bad,” after the repeal of Article 370.

“They shut down the internet! I could not talk to my family very easily. And there were no jobs! It was very hard.”

The Indian Government was widely criticized for throttling the internet, particularly the duration of this move, which they claimed was necessary to combat insurgency.

“Are things better now, than they were before 370,” I asked?

“Yes! There is more investment,” he replied. “My friends have jobs with computers.”

Since the repeal of 370, investment has poured into Kashmir, mostly from other parts of India, but earlier this year, Kashmir got its first foreign direct in investment from UAE, which is opening a mall worth $60 million.

But increased investments have not given Kashmiris more local control. Currently, it is a Union Territory, meaning it is under the control of the central government. The government has pledged ambiguously, that Kashmir will become a state again once the situation “normalizes.”

I later met with officials in Delhi from External Affairs Ministry, as well as intelligence officials, journalists, and others. I was repeatedly assured that the desire to make Kashmir a state with local control again was genuine. It may be the Government’s true goal, but while their security concerns are legitimate, there is a danger it could be delayed by politics.

I lunched with a Kashmiri Pandit now working as a reporter in Delhi. She asked me about my experiences in Srinagar. I recounted much of the above and also mentioned that I’d been to the West Bank and visited Hebron, a place that holds the Tomb of the Patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac and Jacob; sacred to Jews, Christians and Muslims) and sadly has suffered massacres both by Arabs against Jews (in 1929), as well as Jews against Arabs (in 1994). I said it was the only place I’ve felt truly unsafe. The local Palestinian population simply hated the IDF, and the tiny band of Jewish Israeli settlers, and the attitudes of the Jewish Settlers and the IDF was also harsh. But Kashmir didn’t feel like Hebron.

The reporter said she’d been to the West Bank as well and felt unsafe, but didn’t feel unsafe in Kashmir anymore. “They aren’t like Palestinians,” she said, “Pakistan has been trying to radicalize them for 75 years and have failed.”

However imperfectly, life is improving in Kashmir. While some locals undoubtedly sympathize with Pakistan, or are suspicious of the Indian Government, the claim that much of the militancy was driven by Pakistani funding, propaganda and radicalization efforts, seems to have been proven true. India needs consolidate its gains by convincing the local population its actions are a long-term commitment to their interests.

In early 2019, a Qatari government sponsored outlet published an article featuring graffiti saying “Go, India, Go,” which the author believed was the authentic will of Kashmiris.

The only similar graffiti I saw during my trip were the words, “I Love Kashmir” written in the colors of the Indian flag.

It seemed a positive anecdote.