Most Hindus prior to the mid-20th century were almost invariably of Asian descent, as it wasn’t until the counterculture of the ‘60s and ‘70s that those in the Western world truly began taking to Eastern philosophies and traditions in noteworthy numbers.

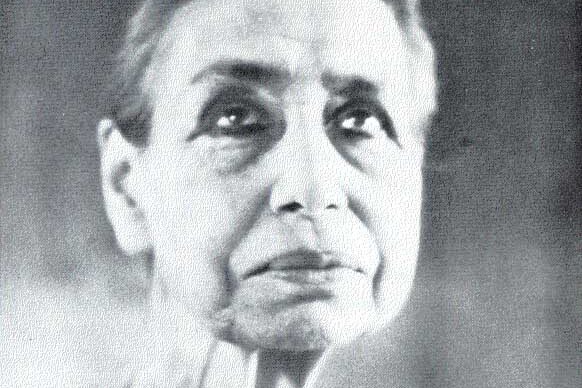

The fact that Mirra Alfassa, a French-born Jew who grew up in Paris in the late 1800s, not only took to Hinduism, but went on to become a prominent guru with an immense following that exists to this day, is therefore more than just intriguing, it’s extraordinary.

Born with a high aptitude for the wide breadth of activities she engaged in during her youth, like music, tennis, art, and literature, Alfassa had many interests, though none permanent. Keenly aware of the world’s forces — be they internal or external — that forced her to act in particular ways, whether she wanted to or not, she primarily desired to understand her identity beyond these forces, and attain inner clarity and freedom.

Between the ages of 11 and 13, her subtle sensitivities sparked what she described as a series of psychic and spiritual experiences that revealed to her the existence of God, as well as “man’s possibility of uniting with Him, of realizing Him integrally in consciousness and action, of manifesting Him upon earth in a life divine.”

Foremost of these experiences involved visions of a luminous teacher, whose appearance in her dreams grew clearer and more frequent. At the time, she knew little, if anything, about Hindu philosophy and religion, yet came to refer to the being as “Krishna,” and was thoroughly convinced that one day she would meet him in the physical world.

While the development of such experiences manifested prominently amidst her natural inclinations and desires, Alfassa was inevitably compelled to fulfill society’s external demands. Leaning into her creative interests, she therefore joined Académie Julian, Paris’ private school for painting and sculpture. A stage in the city’s history when the great painters of impressionism, like Cézanne, Manet, and Matisse rose to international fame, she moved among the cultural avant garde, carving a life as deemed fit by the world around her.

And though she played her societal role to a tee, graduating from the academy, producing successful works of art, getting married, and even having a son — all by the age of 20 — providence, it seemed, would see that she be nudged back in the direction of her spiritual proclivities.

Besides somehow coming across Vivekananda’s Raja Yoga during this period, which helped explain many of the metaphysical experiences she underwent throughout her youth, she also was given a copy of the Bhagavad Gita, one of Hinduism’s most revered philosophical texts, which helped to give her further understanding.

Gaining a growing appreciation for the power of spiritual discipline beyond spontaneous metaphysical experiences, Alfassa’s interest in some sort of systematic spiritual training was answered shortly thereafter by an introduction to the teachings of famed occultist Max Théon.

Wanting to explore his teachings to the highest possible level, she journeyed to the Algerian city of Tlemcen, where he and his wife Mary Ware had an estate. Determined to learn as much as she could, she would ultimately pay their estate two more visits, immersing herself in their practices, including meditating in the enormous heat of the Sahara border.

After completing her time there, Alfassa returned to Paris with a renewed and recharged spiritual focus. Settling into a new kind of life, she began a 12-member study group among whom she distributed translations of the Gita and other Hindu texts, like the Yoga Sutras and Upanishads. Delving even further into Hindu thought, it wasn’t long before she felt irresistibly drawn to India.

Luckily for her, Paul Richard, a well-read philosopher keenly interested in Western and Eastern spirituality, and the man she married after the dissolution of her first marriage, had already been to the country. There, he had met Sri Aurobindo, a renowned yogi and philosopher he was immensely impressed with and had every intention of visiting again.

Hence, in 1914, when Mirra was 36, the couple traveled to Pondicherry, the city of Aurobindo’s residence, and met with him on the afternoon of their arrival. Immediately believing him to be the same luminous “Krishna” who had once frequented her dreams, Alfassa became deeply convinced that her life’s purpose was to assist him in his life and mission.

The start of this assistance began in the course of their stay, as her and Richard started publishing a monthly philosophical journal called the Arya in collaboration with him. Aimed, in its own words, at the “systematic study of the highest problems of existence,” the journal featured a medley of articles by Aurobindo, elucidating his outlook on history, the world, and philosophy.

Sadly, just as the first copies started making it into people’s hands, Richard was called home to join the French Army Reserve following the eruption of World War I. Though Alfassa went back with him, it was not without a heavy heart.

Pulled from where she felt she belonged, only to be plunged into a city marked by the chaos and sufferings of war, she longed for a return to India all the more. While it would be five more years until her wish came true, it was only one year before Richard was ordered to Japan, a place she could appreciate — even if spiritually different from India — for its rich traditions and breathtaking beauty.

As fate would have it, the horrors of the war combined with the natural wonders of the country essentially served to strengthen her powers of empathy and divine intuition. When she finally made her way back to India, she was thus more equipped than ever to surrender to Aurobindo’s spiritual goals. So surrendered, in fact, she would never leave the country again.

Shortly after returning to India, Alfassa’s marriage to Richard came to an end, allowing her the freedom to establish an ever closer collaboration with Aurobindo. At first, she was living outside the house of him and his followers, but was soon invited to move in.

Immersed in his own practices, Aurobindo didn’t act as the residents’ official guru, letting them live somewhat freely without any stringent rules or restrictions. When Alfassa moved in, however, she began organizing the day-to-day function of the household, resulting in a more disciplined schedule, which initially garnered unfavorable responses by those who viewed her as an outsider.

Aurobindo’s immense respect for her spiritual sincerity and potency, however, was undeniable, so much so that he even began referring to her as the “Mother,” through whose compassion he believed would enable him to more effectively help those who sought his guidance.

And as her undeniable devotion and the structures she initiated indeed helped to facilitate a deeper connection between him and his followers, Alfassa gradually became more accepted and recognized by the others, empowering her to take increasing charge of the household.

It was at this time the place truly started to transform into an ashram, drawing in growing numbers of aspirants who heard of the work and principles being taught by Aurobindo and the extraordinary woman known as the “Mother.”

Dubbing their method officially as “Integral Yoga,” the process of integrating the physical, mental, and spiritual aspects of one’s being in an effort towards connecting to the Divine, their ashram was a dynamic center of sadhana (spiritual discipline), health, and work, embracing a variety of occupations, natures, and activities.

Because of this, the ashram’s growth moved at a swift pace, until in 1934 there were roughly 150 people living in more than 20 houses. Fueled by the fervent desire to serve and help those in need, Alfassa also started a school for the children of families who fled to Pondicherry from northeast India during the Second World War. Like the ashram, it grew steadily, flourishing on the energy of her unswerving determination.

This determination endured even when Aurobindo passed away in 1950. Devastated by the loss, her resolve to carry out his mission in the grandest of ways eventually led her to found an experimental township in 1968 called Auroville, or the “City of Dawn.” Located mostly in the state of Tamil Nadu, with parts in Pondicherry, the city was established as a place where people of all countries could come together and live in peace and progressive harmony towards the Divine, regardless of one’s politics, nationality, or religious background.

As the ashram, school, and city — which all still exist and thrive — evolved under Alfassa’s direction, so did her spiritual reputation, to the point where even figures like Indira Gandhi and the Dalai Lama would visit her for guidance. It should thus come as no surprise that when she finally passed away at the age of 95 in 1973, tens of thousands of disciples and devotees came to pay their respects over a three-day period.

Pained by her physical departure, these disciples and devotees take solace in the remarkable legacy she left, a legacy that is ever expanding, of love, power, and unwavering compassion. A legacy charged by her mystifying spirit.

A legacy of the “Mother.”

If you enjoyed this piece, then you may also be interested in reading “Sri Mata Amritanandamayi: The revered hugging saint“