In August 1947, after some 300 years, the British finally were forced to quit India, and the subcontinent was subsequently partitioned into the independent nations of Hindu-majority but secular India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

After World War 2, bereft of the resources required to retain the jewel of its empire, which was growing increasingly unstable amidst India’s desire for independence coupled with the Muslim League’s push for a separate Islamic state, Britain’s exit was rushed, reckless, and woefully executed. Using out-of-date maps and census materials to create the new borders, which awkwardly split the key provinces of Punjab and Bengal in two, Partition triggered one of the largest mass migrations in human history, as the chaos, violence, and brutality that ensued swiftly spread, forcing millions to flee from all over, including provinces like Sindh and the North-West Frontier (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). Resulting in millions killed, millions more displaced, and some 100,000 women kidnapped and raped, the event is undoubtedly one of the worst to have ever taken place, though somehow, it is yet to be recognized as such.

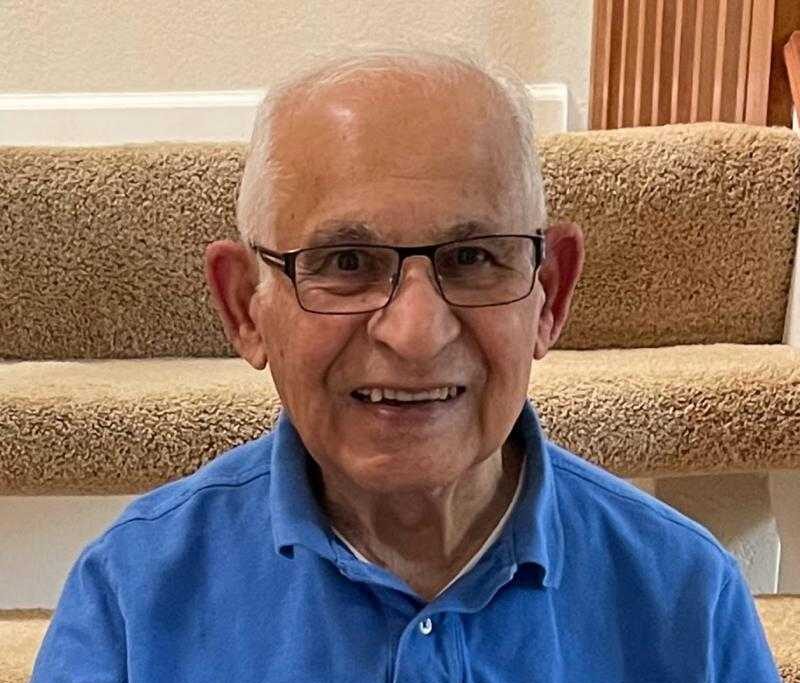

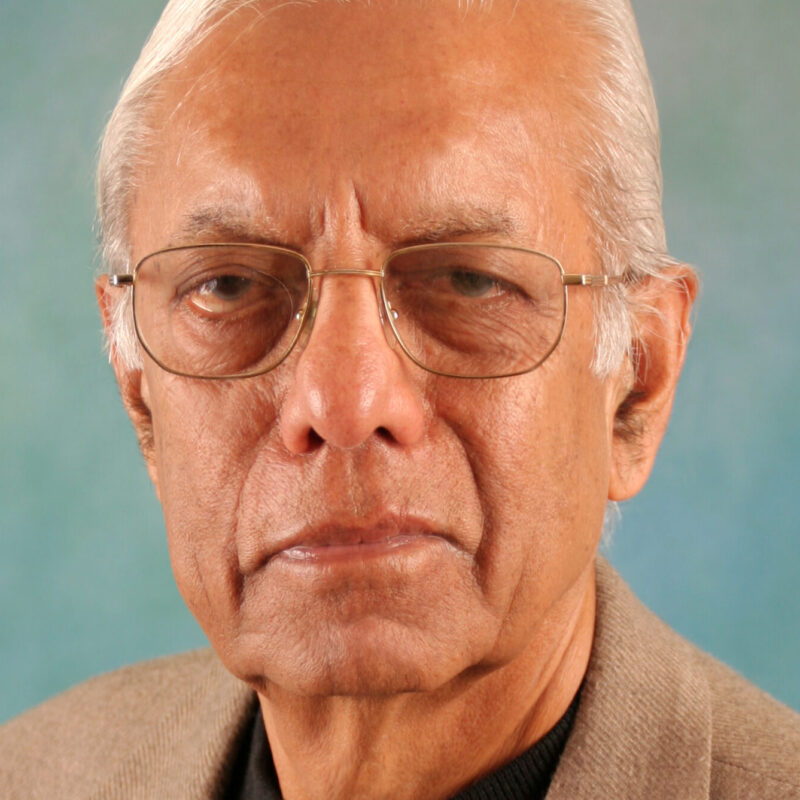

Among those wanting to change this fact is Dr. Ved Nanda, who fled with his mother from their home in Gujranwala (a city now located in the Pakistani province of Punjab) after a Muslim friend warned them their neighborhood was going to be the next target for violence against Hindus. Now a distinguished professor who holds many leadership positions in the global international law community, he’s received numerous national and international awards, including the United Nations Association Human Rights Award, and the Hiroshima Peace Award.

Fueled by his experience during Partition, he has authored numerous books and is a regular columnist for the Denver Post, as he pursues his lifelong purpose of working for human rights, particularly the plight of refugees around the world.

What was life like before Partition, and how would you describe the period directly leading up to it?

Life before Partition for me, as a 12 year old, was full of joy in the family and with friends — playing, school, and fun. It, however, changed dramatically as violence engulfed the region. My father, with the rest of the family, had left for East Punjab to find a place where we could settle. I stayed back with my mother and we watched with horror from our rooftop for several nights as houses burned all over the city.

What feelings and images come to mind when remembering Partition itself? How did you leave your home?

A Muslim neighbor knocked at the door one afternoon and gave us the ominous message: “Tonight your neighborhood is targeted for burning. You better leave.” Panicked, my mother packed some jewelry and treasures in a small suitcase, as needed to help take care of me.

We hurried and our neighbor walked us to the nearby railway station. We heard that the trains going east to Lahore and East Punjab carrying fleeing Hindus were being stopped and passengers killed by armed bands. Hence, we decided to go to Jammu, part of Kashmir, and took the train going west. We had to change trains and, while waiting a few hours at Wazirabad Junction, it got dark and I fell asleep on a bench. A thunderous noise woke me — a bomb had fallen nearby. As we ran for cover, my mother left the suitcase behind as she was more concerned about saving my life.

The train for Jammu was stopped on the way by a group of armed men who boarded a few cars and stabbed and killed several passengers in other compartments. But in our compartment there was a Sikh soldier with a rifle who fired a couple of shots, so no one entered our compartment. After the train was able to depart, we soon reached Jammu, with the clothes we were wearing as our sole possessions.

In Jammu, the local Hindu community had set up a camp for those like us who were uprooted. For the next few months (I can’t remember the exact duration), we stayed in the refugee camp, because walking from Jammu to East Punjab was still not safe. Eventually, along with thousands of others, we started walking toward East Punjab. It was a long walk, about 200 miles.

All that time, since we left Gujranwala, we could not reach my father by mail or telegraph, hence he did not know we were alright and assumed we were killed. By the time we reached Malerkotla (a city located in East Punjab), where he had found a place for us to live, the family had already done the Hindu last rites for us. We finally were able to get to them and were tearfully and joyfully reunited.

What was life like after? What of everything you endured during that period was the most challenging?

The challenge of that period for my parents was obviously to settle in a different place, to start afresh after losing everything, including two houses and all their possessions. Fortunately, my father was in the Indian Civil Service and hence, after coming to East Punjab, he had work.

I eventually went on to study at Punjab University in Ambala and then at the University of Delhi. I did M.A. in Economics and LL.B. and LL.M. before I came to the United States for further studies at the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and Yale Law School. After an internship at the UN, I began teaching law.

For me, as a young boy, what I witnessed in the refugee camp and along the 200-mile walk were things no one should ever have to see. That, indeed, has been the greatest challenge of my life; but experiencing my mother’s courage was the greatest inspiration.