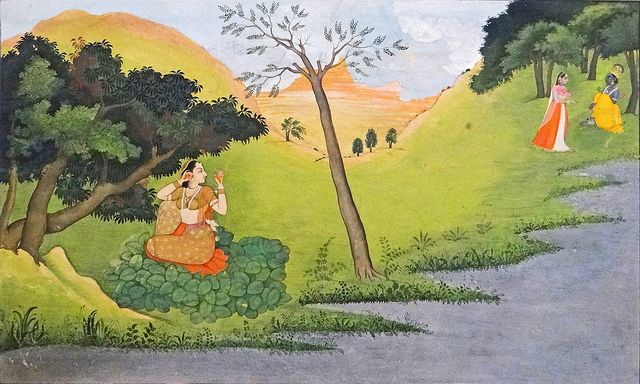

For those who follow Hindu traditions like that of Gaudiya and other forms of Vaishnavism, in which Krishna is worshiped as the ultimate form and source of the Divine through the process of bhakti yoga, or loving devotion, there is no place like Vrindavan, the village he is described as having grown up in roughly 5,000 years ago.

Brimming vibrantly with more than 5,500 temples dedicated to his worship, a constant stream of festivals celebrated in his honor, and throngs of devotees bustling to see the myriad of lakes, rivers, forests, hills, and lands where he is believed to have played out his countless childhood pastimes, the now historical city is a spiritual oasis, offering pilgrims an unending repository of devotional wonders.

And yet, even as these wonders have a sort of whirlpool effect, pulling devotees into the expanse of their extraordinary depths, they also, strangely enough, have the tendency to actually propel devotees back out of Vrindavan.

How is this so? What could possibly compel pilgrims aspiring for Krishna bhakti to spend what limited time they have during their travels to go outside the storehouse of fathomless bhakti that is Vrindavan?

The answer, simply put, are those places where such fathomless bhakti can somehow be explored even further.

One of these places, which shines unlike any other jewel in the crown of bhakti yoga, is the Shrijii Temple in Barsana, dedicated to Radharani, who grew up in the village (now historical town) located roughly 30 miles northwest of Vrindavan.

Known as Krishna’s eternal consort, whose expression of love is so profound it bewilders even him, Radharani is regarded as the “queen of bhakti.” In a spiritual lineage where the primary goal is to develop love and devotion, this makes her, in some sense, the tradition’s most important figure, and thus her temple a most potent place of pilgrimage.

Believed to have originally been established around 5,000 years ago by Krishna’s great-grandson King Vajranabha, the temple was eventually washed to ruins by the waves of time, as its deities, affectionately called Ladli (“dearly beloved daughter”) and Lal (“dearly beloved son”) — commemorating their childhood pastimes — fell out of the world’s sight.

That is, until the 1500s, a period when a Gaudiya devotee by the name of Narayana Bhatta, thought by many to have been an incarnation of the great sage Narada, came along.

Depicted throughout numerous Hindu texts as a wandering saint with extraordinary spiritual potency, it was Narada who Radharani’s father, King Vrishabhanu, approached for help, when she seemed unable to open her eyes during the first couple years of her advent on earth.

Fearing she might be blind for life, he placed her on the sage’s lap, hoping he might be able to perform a miracle. Upon holding the child, Narada immediately became inundated by a feeling of indescribable love and happiness. Overcome by emotion, tears flowed from his eyes, as the baby revealed to him her spiritual identity. Managing to compose himself, he handed the baby back to the anxious king, telling him not to worry, and that soon all would become perfect.

Shortly after Narada’s visit, Vrishabhanu arranged a festival, the attendees of which included King Nanda, his wife Yashoda, and their one-year-old son Krishna. At some point during the festival, Krishna crawled up to the cradle in Radharani’s room, pulled himself up, and looked inside. Sensing that he was near her, Radharani finally, for the first time, opened her eyes, and looked upon her beloved, revealing that she had no real interest in any other sight the world had to offer.

Always looking for new ways to open the world’s eyes to the depth of Radharani’s immense love as he experienced it that day he held her, Narada’s purported life as Narayan Bhatta was spent wandering the lands of Radha and Krishna’s childhood, finding many of the couple’s lost deities and reestablishing their worship.

As such, it was he who discovered Ladli and Lal, subsequently installing them in a newly constructed temple, where they continue to be worshiped today.

Built on the site of King Vrishabhanu’s palace where Radharani used to live, the structure — made up of red and white stones symbolizing her love for Krishna and his love for her — is aesthetically bedecked with elegant domes, elaborate arches, intricate hand carvings, and beautiful paintings. Requiring the visitor to climb some 200 steps to reach its gate, the temple, in all of its magnificence, overlooks Barsana from a hilltop — and not just any.

Called Bhanugarh, this hill, as related in Hindu texts, is considered to be a manifestation of Brahma, the architect of the universe who, after pleasing Krishna, was granted the great boon of appearing in the mountainous form, so that he could better understand the couple’s profound mood of devotion by not only witnessing their pastimes, but actually playing a role in them as the ground on which they took place.

Also hoping to better understand and tap into this mood of devotion, millions of pilgrims make their way to the temple every year, particularly on big festival days like Radhashtami (Radharani’s birthday), Janmashtami (Krishna’s birthday), and Holi (the “festival of colors” known for commemorating the love between the couple in a uniquely jovial and playful manner).

It is on such festivals, after all, the Shriji Temple feels especially charged with Radharani’s unparalleled feelings of unconditional love, reminding all who go during those times that there may be no place like Vrindavan when it comes to Krishna bhakti, but it’s the queen of bhakti, and all following in her footsteps, who make it that way.

If you enjoyed this piece, then you may also be interested in reading “5 things to know about Radharani”