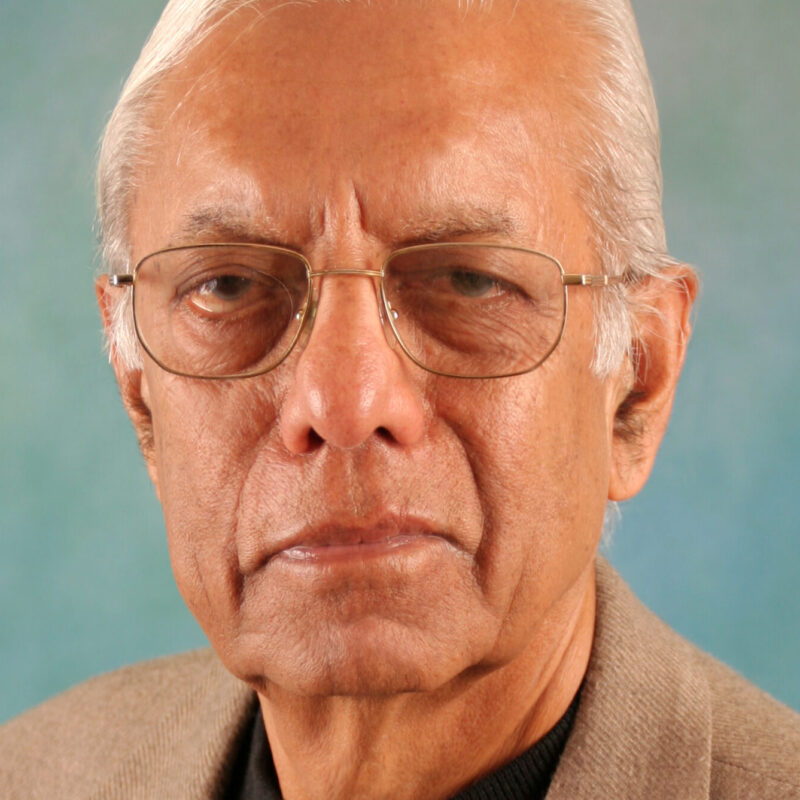

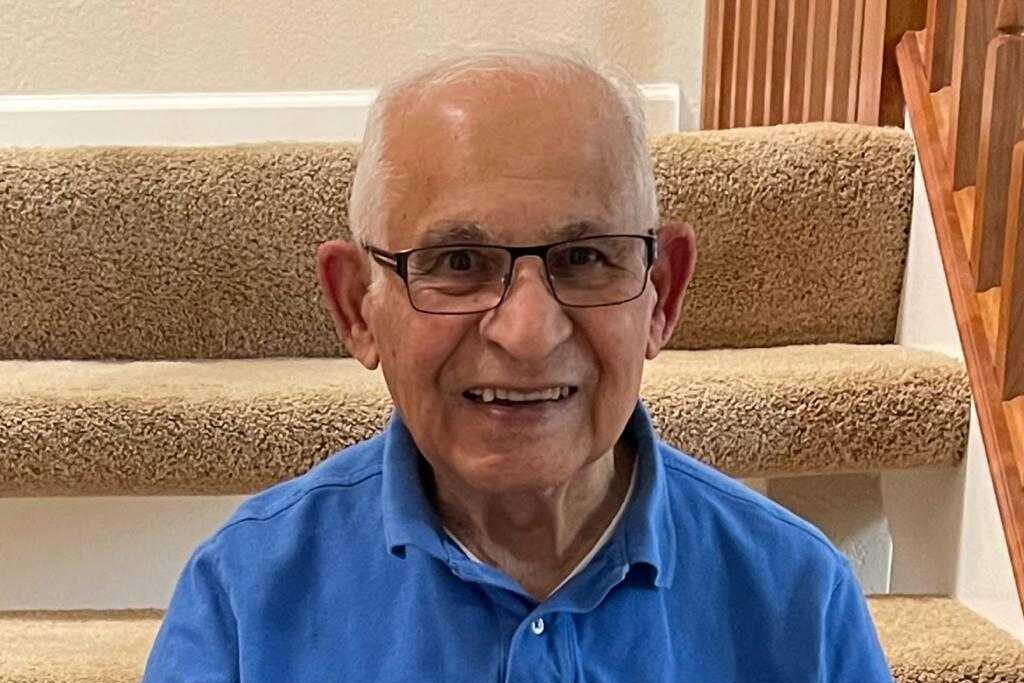

Kalra poses for a photo at his home in California 75 years after surviving Partition. It is, undoubtedly, one of the worst atrocities to have ever take place.

What was life like before Partition?

I was born in Lahore in 1936, but spent the first seven years of my life living in the city of Peshawar in the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). I remember the three different locations we lived in. The first two we shared with another family. The last was a small house in a very nice neighborhood that was part of a government quarter’s area. Made up of many other similar houses, the area was like a sort of colony with a big park in the center we used to play in during the evenings.

On one side of this colony there were really large bungalows with flowers like roses and sunflower bushes. On the other side was a slaughter house and we could see blood moving in the open gutter. I only came across Hindus at that time as far as I remember, but I was young and didn’t fully understand much about religion.

In 1943, I lived with my paternal grandparents in Lahore for approximately 3 months. At that time they were living in an area known as Janakpuri, which was 100% Hindu. I was there during Diwali, and remember participating in children’s races and fireworks.

In 1947, my father moved to Dhrangadhra, Gujarat for work and my mother decided to take my two brothers and I to visit her parents in our ancestral town of Dera Ismail Khan (located in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), before also going to Dhrangadhra. After a couple of months in Dera, we found out that my bua (paternal aunt) and dada (paternal grandfather) in Lahore had passed away, and so my mother traveled to the city with my two brothers to see family there before finally moving to Gujarat. Because I was supposed to be in school and my mother was concerned about how having to learn a new language would affect my schooling (all of my education up until then had been in Urdu), she decided to leave me with my nana (maternal grandfather) and nani (maternal grandmother) in Dera, and have me continue school there.

Dera was a good-sized city. Most people there — Hindus and Muslims — lived in separate areas. We lived on a long street (Shiv Shah Street) with about 100 homes. One end of the street was walled in, while the other end had a large gate, which closed at night and opened in the morning. Behind our house, there was a road and another walled-in area, which was a Muslim neighborhood with a mosque. From there, I could hear the Muslim call to prayer very early every morning.

The only interactions I generally had with Muslims were either at the market while buying vegetables, or when they would come to our home to deliver firewood. My nana however, who had been a doctor in the government hospital, had a lot of positive interactions with Afghan and local Muslim patients. He was even fluent in Pashtun.

Like many other Hindus in that region, several of my relatives were active with the Arya Samaj (a religio-social organization), which was popular amongst Hindus in Punjab and the North-West Frontier. They would also regularly visit the local gurdwara.

How would you describe the period directly leading up to it?

Though I stayed in Dera for school, I never actually ended up going as we learned, on what was supposed to be the first day, that the building had been burned down. According to the local Muslims, it hadn’t been done by them, but by Afghan extremists. In any case, the school was never opened and I was never able to attend, though I continued to stay in Dera.

As tensions continued to rise leading up to Partition, my father

In August 1947, after some 300 years, the British finally were forced to quit India, and the subcontinent was subsequently partitioned into the independent nations of Hindu-majority but secular India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

After World War 2, bereft of the resources required to retain the jewel of its empire, which was growing increasingly unstable amidst India’s desire for independence coupled with the Muslim League’s push for a separate Islamic state, Britain’s exit was rushed, reckless, and woefully executed. Using out-of-date maps and census materials to create the new borders, which awkwardly split the key provinces of Punjab and Bengal in two, Partition triggered one of the largest mass migrations in human history, as the chaos, violence, and brutality that ensued swiftly spread, forcing millions to flee from all over, including provinces like Sindh and the North-West Frontier. Resulting in millions killed, millions more displaced, and some 100,000 women kidnapped and raped, the event is undoubtedly one of the worst to have ever taken place, though somehow it is yet to be recognized as such.

Among those wanting to change this fact is Narendra Kalra, who fled with his grandparents from their ancestral home in the North-West Frontier after Muslims took over their house and neighborhood amidst the violence. A former mechanical engineer who is now retired, he shares his story with HAF, hoping to shed light on the atrocities of Partition, and how the horrors of that period continue to affect people today.

and paternal grandmother decided it would be better if I went to live in Lahore, so they made travel arrangements for me to go there. But before I could get on the buggy that was supposed to take me to the train station, my nana, who suddenly had a bad feeling, changed his mind, and stopped me from leaving. We later found out that the train I would have traveled on was attacked, and all the people on it (Hindus and Sikhs) were butchered.

When Partition talks were going on, many from our street, though a relatively safer area at the time, began leaving, while many — including my youngest masi’s (mother’s sister) family and extended family who lived in nearby areas more exposed to the violence — actually sought shelter in our neighborhood. My masi’s family, in particular, was targeted because her husband was a community activist who was outspoken on Hindu-Muslim relations.

As Partition grew nearer, I remember hearing about curfews and riots taking place in the city, as the gate on our street was locked, and people stopped coming in and going out. For many days, we couldn’t go out to get fresh vegetables, and so lived only on food that was already at home, like dal (lentils) and roti (whole wheat flatbread). We also couldn’t even get the outhouses cleaned.

I didn’t witness violence myself because they tried not to let us go out as kids, but I heard a lot about it. At the end of the street where it was walled off, some people from our neighborhood created a platform and sat on top with guns to protect the area. I heard gunshots at times but I wasn’t sure if they were fired into my street, or from my street to the outside.

When the curfews ended, many more Hindus started leaving for India and many more of the houses became empty. Many who left still had relatives living in the villages, who came to our neighborhood and used it as a transition area before migrating to India by train or bus.

My youngest masi left and went to Delhi. My nani’s younger sister came from a village to live with her brother, and then left the area to go to India. One of my dada’s relatives also came from the village and lived on our street for a couple of months before leaving for India. My eldest masi in Lahore had gone to stay with her sister in Delhi before Partition, thinking she would return home after things settled down, but she never did.

After Partition, when things started to get normal again and people went back out to the market, I began going into town and visiting relatives who were still there. The government hospital where my nana used to work asked him to come back even though he had already retired. Happily agreeing to serve, he was picked up by a jeep every morning and then dropped off in the evening. At this point, he had decided that he didn’t want to leave Dera, and would stay as long as he possibly could. He was, after all, in his mid 70s, and had no desire to have his life uprooted.

Kalra’s nana, or maternal grandfather (right), poses for a photo with his friend and colleague in the North-West Frontier (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) prior to Partition. It was in Dera Ismail Khan his grandfather worked as a doctor in a government hospital, regularly interacting with local Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim patients.

When and how did you leave your home?

Many of my father’s relatives who were living in Lahore ended up leaving because of the widespread riots. When my uncle, who was in the military, heard of the danger, he immediately went to my dadi’s in a jeep, who was at home alone, and helped her escape. Told to flee as fast as she could, she didn’t pack any clothes, or even have the chance to put on her chunni (a type of scarf) or shoes. Her house, as it turned out, was burned down and destroyed after she left.

She and my other relatives were taken to Model Town in Lahore. From there a military convoy took them to the border, after which they went on to Jalandhar. Model Town became a transition area where people from the Pakistani side were taken to the Indian side and people from the Indian side came to Pakistan. By April 1948, most of my relatives had left and my nana was getting a lot of letters from relatives in India to follow suit, and so he finally decided to leave.

Prior to leaving, my nana gave the house to a Muslim acquaintance on the condition my nana could reclaim the house if he managed to return. After thus completing the necessary paperwork for the agreement, we left on a bus, with some of the other remaining Hindus from our neighborhood, for Darya Khan, a town in which the nearest train station was located. From there we were supposed to take the train, but it was so crowded, with people even climbing on its top, that we couldn’t get on, so we just stood on the platform and waited. While there, we noticed other Hindus who were also waiting being looted while the police watched and did nothing. I remember feeling scared and crying as I grabbed on tight to my nani.

Feeling it was unsafe, my grandparents, along with the other Hindus we had traveled there with, decided to just get back on the bus and return to Dera. When we got there, however, not only was our house occupied by Muslims, but our whole street was, so we went to stay in what served as both a Hindu temple and gurdwara, which was located nearby. Fortunately, necessary arrangements were made, and the next day my grandparents and I were able to board a Red Cross plane prioritized to help children and the elderly escape. Falling asleep on the flight, when I woke up, we were at the train station in Ambala, a city on the Indian side of Punjab.

I later heard from relatives that the train we were supposed to take from Darya Khana ended up being attacked and most of the Hindus on it were butchered.

What was life like after? Did you or any family members live in refugee colonies, and if so, what was that like?

My mama (mother’s brother) and mosa (mother’s brother-in-law) met us at the Ambala train station and escorted us to Delhi. There, my two masis, with their families, were staying with their sister in a very small flat, and my mama and grandparents were staying at my cousin’s flat.

My grandparents and I also ended up staying at my cousin’s place. We were three families living in a three-bedroom flat, so it was very chaotic. After three months, my mother came from Dhrangadhra to get me. At that time the journey from Delhi to Dhrangadhra took more than 24 hours and involved changing trains three times.

Fortunately my nana, who had been a government employee, got a pension and received some regular income, so he and my nani were better off than my other elderly relatives, who had a lot of difficulty adjusting to life since they had lost all their properties and farmland back home.

In Dhrangadhra I spent the next four years finishing high school, after which I went back to Delhi to visit my nana and nani. Now 1952, things there were completely different. All my relatives had been given small houses in refugee colonies in Rajinder Nagar and Kingsway Camp (two of the many refugee colonies set up by the government).

Kalra’s nana’s refugee registration card.

What was it like rebuilding your life? What of everything you endured during that period was the most challenging?

I had to learn Gujarati from scratch — prior to that, my schooling was all in Urdu. Luckily, I had taught myself Hindi before with the help of my mother, so it made learning the alphabet in Gujarati a little easier.

Dhrangadhra was a very small town at that time. It had a population of about 20,000 and hardly any who spoke Hindi. It was always a little difficult assimilating into the culture even though people were nice. I had to wing it many times. On the first day of school, for example, they asked what my name was. When I said “Narinder Nath,” and they wrote down “Narendra Nath,” I decided to just go with it, and so that became my name going forward.

Though my father didn’t really experience any financial problems — he had a job and was working most of the time — my parents did have trouble finding a place to rent when they first moved to Dhrangadhra, because they were mistaken for Muslims as my mother always wore a salwar kameez, which no Hindu ladies wore at that time. One of the elders from the Arya Samaj temple my father met, however, helped get them a place. After assimilating as such, they didn’t really have any problems.

How did the challenges of that period differ from the older generation to the younger? (In other words, how was it different for you versus your parents or grandparents or other relatives?)

Because I was young and could therefore adjust to a new life more easily, things were much less difficult for me. For many of my relatives who were old, however, they naturally felt a bitterness about Partition, as they lost everything. My youngest masi’s husband, who had had income from various investments, rental properties, and farms, experienced the most difficulty — as did another masi’s husband. But for those who were able to make it, they felt they had to move on. What else could they do?

All of the relatives talked about how they missed their old lifestyle. How they used to have a nice life back home in Dera, where they all lived close to one another and could visit each other often.

What positivity, if any, came out of your people’s struggle?

People are now more aware of their religious similarities and differences. Because we were forced to leave our homeland, we, as Hindus, have come to recognize and appreciate our culture and identity more.

Despite the fact relations varied considerably by region and by ruler, Hinduism and Islam managed to exist alongside each for close to a thousand years in India up through the 19th century. What, in your eyes, caused these relations to deteriorate so immensely in the two-decade period leading up to partition? What, specifically, led to such violence and horror?

We may have existed alongside each other, but there was only a truce because Muslims, who ruled for a long time, were able to convert Hindus quite easily. Other than that, I’d say, for the most part, relations were always strained between Hindus and Muslims even when they appeared ok externally. There were, of course, always exceptions, but given the history of the relationship, it was not surprising that such violence took place.

What have been the ripple effects of Partition from one generation to the next? How have you/do you pass on memories to children and grandchildren?

We didn’t lose our culture completely — I used to speak my native language of Derawali (a dialect of Punjabi) at home with my mother — but overall, as we assimilated to our new circumstances, there was some loss of identity and culture.

For those who lived in the refugee colonies in Delhi, many were able to hold onto their culture and language at first. My youngest masi’s husband, for example, started a newspaper called Derawal Sandesh, which was published in our language. Each generation, however, held onto less and less, and the reality has become that very few people in India and the diaspora can speak the language anymore.

I’ve tried to tell my kids the stories I remember about that time and what happened. I’ve also shown them old pictures and have taken them to visit some of my relatives who lived in Rajinder Nagar many years ago. The more my children have asked me about Partition and its period, the more I’ve told them, as they, in turn, tell their own children.

Taken after she was widowed, Kalra’s nani, or maternal grandmother, poses for a photo while living in Rajinder Nagar (a Delhi refugee colony) during the 1950s. All of Kalra’s relatives in Delhi had been given small houses there.

How do the events of Partition continue to affect life throughout the subcontinent (India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) today? In retrospect, are you convinced that Partition was ultimately for the best?

It’s difficult to say whether Partition was for the best. I’d say the jury is still out. Ultimately, Hindus lost out on more proportionately, as many Muslims were able to remain in India and keep their properties, while many were also able to secure land with the creation of Pakistan.

Most Hindus, on the other hand, were forced to uproot their lives and leave Pakistan, while the few who stayed behind had miserable lives. It was, thus, much more of a lose-lose situation for them.

Have you had a chance to go back to your childhood or ancestral home? What would you like to see or do “back home,” if given the chance?

I haven’t had the chance to go back and visit yet. If I had the chance, I’d like to see some of the old neighborhoods where my family lived, the neighborhood where I was born and used to visit my paternal grandparents in Lahore, our old homes in Peshawar, and my home in Dera.

Many years ago, I came across a person from Dera in California who previously worked in the Indian Embassy in Islamabad after Partition. While he was in Islamabad, he wanted to visit Dera, but the Pakistan government advised him not to go there, stating it may not be safe to do so. It’s still not safe there.

What is your hope for the future?

To be able to accept the situation as it is and move on. And that all countries involved respect the sovereignty of each, modernizing in a way that’s beneficial for all.