In Gujarat, Narsinh Mehta is revered as Adi Kavi, or the “first poet” of the region’s language — not because no others came before him, but because his lyrics were the first in the vernacular to become widely shared among its speakers.

Conveying messages of love, compassion, self-reflection, and human dignity, his poetry contains a universal quality that has enabled it to flourish throughout the centuries and evolve into something beyond that of popular religion.

And what is it that has fueled such popularity?

An unswerving devotion to Krishna, one that is so profound, simple, and pure, it is blind to the designations of class, creed, and color, thus having the ability to speak to all, regardless of time or place.

The journey of this devotion — which must be gleaned from Mehta’s autobiographical poetry, as there is little available historical documentation on his life — is filled with miracles and mystical encounters, the likes of which began at an early age.

Born into a 15th-century community of upper-class Hindus known as Nagar Brahmins, Mehta was raised by his grandmother, Jayakunvar, after losing his parents when he was roughly five. Unable to speak during the first eight years of his life, he is said to have suddenly gained his speech when he came across a sadhu who asked him to chant “Radhe Shyam” (“Shyam” being another name for Krishna), to which Mehta was miraculously able to do so. From that moment, the seed of Krishna bhakti (devotion) had been sown in his heart, and he began spending much of his time with sadhus and ascetics.

When he came of age, his marriage was arranged to a woman named Manek. Though they shared a loving relationship and had two children — a son and a daughter — Mehta could not make much of a living, as he continued to spend most of his time wandering in the company of renunciates.

Because of this, his sister-in-law had little respect for him, and one day ridiculed him for his inability to support his family, calling him a burden. Deeply hurt by her scolding insults, he left his home, and roamed aimlessly, eventually finding himself in front of a dilapidated Shiva mandir (temple).

Deciding to end his life, he proceeded to meditate there, abstaining from food and water. After seven days of this, it is said Shiva, impressed with Mehta’s austerity, appeared before him, offering to fulfill any wish he desired. Humbled and overwhelmed in his presence, Mehta asked to be given what was most dear to the god himself.

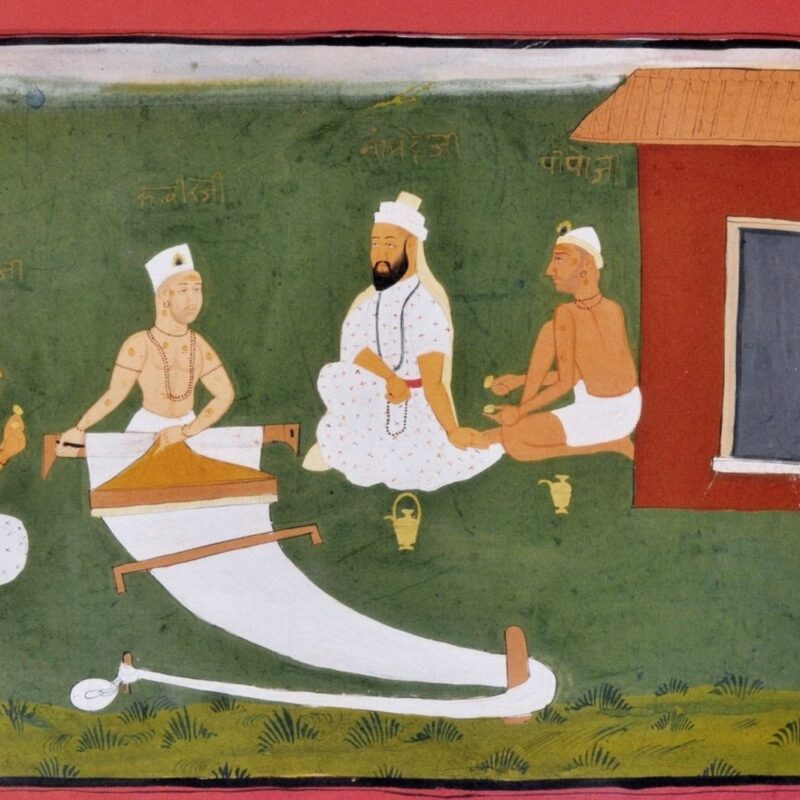

Pleased by Mehta’s request, Shiva transported him to a spiritual realm where Mehta could see Krishna engaged with his most intimate devotees, the gopis of Vraj (Krishna’s female friends), in a pastime known as the rasa lila.

Understanding Shiva’s fondness for this pastime, Mehta watched as Krishna and the gopis, concealed in a forest during the hours after the people of their village had fallen asleep, expressed their true feelings for each other in a divine dance of love, uninhibited by the encumbrances of daily responsibilities that so often got in the way.

Given the duty of holding a torch to help light the dance grounds, Mehta was so entranced by the performance, and so stirred by the exhibit of devotion, that he didn’t even notice when the torch began burning his hand.

Moved by Mehta’s own devotional display, Krishna, wanting to give something to the torch bearer for the service he provided by helping light the grounds, asked, like Shiva before him, if there was anything Mehta desired. Profoundly affected by what he had witnessed, Mehta told Krishna there was nothing he wanted more than to be his eternal servant, and to be able to sing his glories throughout every lifetime.

Happily granting Mehta’s wish, Krishna, who is controlled by the love of his devotees, also ensured Mehta that he would be there for him whenever he was needed.

Vaisnava Jan To

Only he is a man of God

who understands the pain of others

one who does good to others

without letting pride enter his mind

One who finds good around the world

without finding faults in anyone

Who keeps his words, thoughts, and actions pure

his mother is blessed

One who sees equally, gives up greed

respects women like his mother

and who tirelessly speaks the truth

and does not eye else’s property

One who gives up attachments

whose mind renunciates

The name of Ram is on his lips

whose pilgrimage is within

One who is not greedy or deceitful,

and is free of lust and anger

O Narsi, in the company of such a person,

the entire family gets salvation

O Torchbearer is Narsaiyyo

O torchbearer is Narsaiyyo! Torchbearer of Hari!

With mind brimming with deep love

And nectar on his tongue,

O torchbearer is Narsaiyyo! Torchbearer of Hari!

A group of girls, overflowing with ecstasy

And dancing in circle with abandon;

Some clap while some warble sweetly,

O torchbearer is Narsaiyyo! Torchbearer of Hari!

The girls enjoy the very thing they so relish,

And their glances are playful and inviting,

In such an engrossing moment,

Narsaiyya’s manliness has vanished!

O torchbearer is Narsaiyyo! Torchbearer of Hari!

Elated by Krishna’s blessings, Mehta returned to his home, where he began taking care of his family with new vigor, and dove into his eternal vocation of singing about Krishna’s aspects and their glories.

Interestingly, such aspects, in Mehta’s eyes, were not limited to only personal attributes, as his lyrics consisted of contemplations on the all-pervading formless facet of the ultimate truth, as well. Furthermore, his compositions also include reverential praise of Shiva, whose compassion played a vital role in Mehta’s spiritual transformation and evolution.

Because his poetry thus bridged the gaps amongst communities of various philosophical and devotional outlooks — those who worshiped Krishna, those who worshiped the all-pervading Divine, and those who worshiped Shiva — his lyrics carried wide appeal.

And since all of it was sparked by his witnessing of the rasa dance, the vision of the performance never leaving his mind, his works were underlaid by a devotional sentiment similar to that of the gopis, whose love for Krishna is considered unrivaled in all of existence.

The power and joy of this love, therefore, overflowed from his being in waves of compassion, inundating the people around him indiscriminately, as he saw all of them as equally spiritual in nature, a teaching fundamental to general Hindu thought.

As such, he sang and danced in the company of all kinds of devotees, regardless of their gender or social status. This, however, disturbed the high-ranking religious figures in his city of Junagadh, who falsely believed the status of a person’s birth had anything to do with spirituality.

When Mehta’s popularity as a singer thus began growing, they orchestrated a medley of situations hoping to tear down his reputation. But because he always remained absorbed in his devotion, nothing affected Mehta, for Krishna, as promised, came to his rescue every time.

One of these orchestrations took place when the priest of a well-respected nobleman, Madan of Vadnagar (a town in north Gujarat), came to Junagadh in search of a suitable husband for Madan’s daughter. A local Nagar Brahmin suggested Mehta’s son, Shamaldas, as a potential candidate, hoping the priest, after seeing the singer’s lack of wealth, would spread stories of his poverty. But to the Nagar Brahmin’s dismay, the priest, upon meeting Shamaldas, was actually impressed, and swiftly chose him for Madan’s daughter, announcing the engagement.

Yet, hope for the ill-disposed Nagar Brahmin and his supporters didn’t die, for they knew that when Mehta and the groom’s party arrived for the wedding with little wealth and no gifts to offer, the bride’s family, and all the guests, would see for themselves how poverty stricken Mehta’s family truly was.

Completely unconcerned and unaffected by the possible humiliation, Mehta put little to no effort into the wedding arrangements and instead traveled to Dwaraka — the city Krishna is said to have once lived, but for Mehta, whose presence was still very real — to personally invite his beloved Lord to the ceremony.

After returning to Junagadh, Mehta and the wedding party left for the ceremony location looking indeed like a band of paupers and mendicants. Anticipating the lackluster reactions the impoverished group would garner on arrival, Mehta’s ill-wishers eagerly waited amongst the guests, but were stunned when Mehta, Shamaldas, and the rest of the group appeared with great pomp, grandeur, and numerous gifts beyond imagining.

Legend has it that it was Krishna himself who miraculously showered the group with riches, providing everything needed for the son of his great devotee to have an opulent wedding celebration.

As the prestige of Mehta’s immense devotion continued to spread, another incident took place involving the king of Junagadh, Ra Mandalik. Wanting to put Mehta’s bhakti to the test, Mandalik commanded him to sing in the royal court until Krishna, moved by the sincerity of the singing, personally delivered the saint a garland that was hanging from a murti in the nearby Damodar temple. Instigated by more ill-wishers from Mehta’s own community, the king threatened to have him killed if the garland never arrived.

That evening Mehta began singing, but hours went by and nothing happened. Losing patience, the singer grew angry, not because he feared for his life, but because he knew that if he failed, the many he inspired would lose faith in the path of bhakti. All night he pleaded through song until, right as the sun appeared from behind the horizon, Krishna too appeared, placing the garland around Mehta’s neck. Stunned by what he saw and mortified by how he had treated the saint, Mandalik apologized profusely to Mehta, who happily forgave him.

Though there are yet several other mystical events in Mehta’s life that could be told, the next and last that will be discussed — in the interest of keeping this piece from reaching an unreasonable length — is one that emphasizes the power of the saint’s egalitarian disposition.

Once, the Nagar Brahmins, highly offended that Mehta had been regularly singing and dancing amongst communities they viewed as being beneath them, excommunicated him, making a point to exclude him from a feast he would normally have been invited to.

When they sat down to eat, each noticed, to his disgust, that all of the preparations were filled with worms. Upon looking up, each also saw that the person sitting next to him inexplicably appeared to be a member of the “lower” community that all of them so disdained.

As confusion and chaos ensued, one of the attendees, believing perhaps this was all occurring due to the offense of not inviting Mehta, quickly had an invitation sent out to the saint who, upon reception of the invite, swiftly made his way to the event.

Reaching the feast, Mehta’s arrival made everything appear normal again, immediately quelling the chaos, and showing to all who were there, the absurdity of their pride and vanity.

It was this lesson, perhaps more than any other of his, that rang loudest, and has been most enduring, inspiring the likes of Mahatma Gandhi who, like Mehta, hailed from Gujarat, and also experienced alienation from his community for interacting with people from all social backgrounds

Highlighting just how much Mehta inspired Gandhi, Professor Neelima Shukla-Bhatt, in her book Narasinha Mehta of Gujarat: A Legacy of Bhakti in Songs and Stories writes, “The references to Narasinha in Gandhi’s writing indicate that the saint-poet’s songs formed an integral part of Gandhi’s inner world and that the saint’s sacred biography, with its marked stress on voluntary poverty and empathy for the downtrodden, offered him a model to emulate as well as to invoke in public life. Gandhi also found in these songs and narratives valuable resources to support his social and political ideology.”

Of Mehta’s works, the song Vaishnava Jana was Gandhi’s favorite, in large part due to how it outlines the virtues of a spiritual person in a way that speaks to not just Hindus, but people of all religious ideologies. Including it in his ashram’s book of bhajans (devotionals), singing it in his daily prayer meetings, and reciting it at public events, the composition was, and continues to be, a universal anthem of world peace.

Such is the power of words imbued with pure love and devotion, that when they are spoken or sung, they can move the hearts of all types of people, no matter the time, place, or circumstance. Such was the power of Narsinh Mehta.