His name is Arabic for “great,” and so he was for what he gave to the world : a collection of poetic works that are recited and sung more than 500 years after his time, touching and inspiring the lives of millions, and not just in India, but throughout the world.

Indeed, the power of Kabir’s words, known for their nirgunbhakti, or personal devotion to the formless and impersonal Divine, imbibe a quality that transcends not only time, but the borders of religion, stirring a desire to serve in the hearts of Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims alike, all who have claimed him as their own.

Yet, to say he belongs to any one of them alone, would be an egregious affront to his legacy, the likes of which challenges the notion that any one religion can hold a monopoly on the ultimate truth. Such truth, rather, is available to all who take to the path of righteousness, and it was on the current of this fundamental teaching that all of his poetry has been able to flow, clear and bold.

His own life is shrouded in mystery and legend, accounts of which have been retold numerous times throughout the centuries. But to fully grasp the layers of depth behind Kabir’s words, it helps to understand the details of his life — even if those details are shrouded — and the socio-cultural backdrop against which his story unfolded.

In one account, his mother is described as being a devout Hindu widow who, while on pilgrimage with her father, visited a famous ascetic. Pleased by their dedication, the ascetic blessed the widow, telling her that she would soon give birth to a son.

As his words came to pass, and the son was born, the widow, scared of the dishonor that having a child out of wedlock would incur, abandoned him at the Lahartara Pond in Varanasi. Soon after, he was found floating on a lotus by a Muslim weaver named Neeru, and his wife Neema.

In another version, Kabir is born from his mother in an unusual manner, as deemed by the ascetic, emanating from her palm. And in yet another version, he is said to have come from a body of light, appearing directly on the lotus itself. In any case, his birth is believed by many to have been under miraculous circumstances, after which he was discovered and then raised by Neeru and Neema.

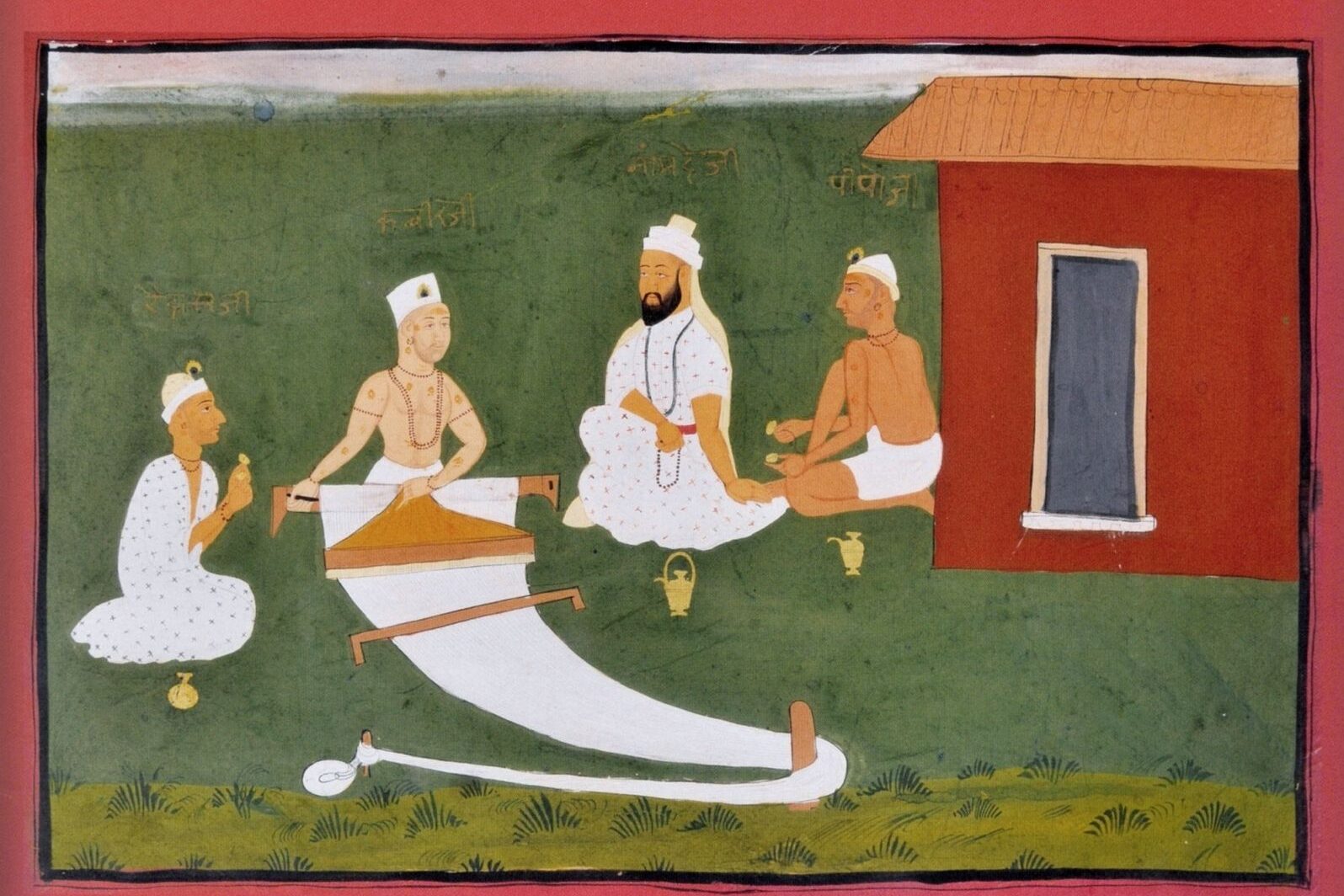

Like his adopted parents, Kabir became a weaver by profession, and perhaps even got married and had child or two, though there are those who maintain he remained a celibate his entire life. Either way, his heart was not in his means of income, and he did not undertake any sort of formal education.

The kind of education he sought, instead, was of a spiritual nature, and he hoped that the Hindu Vaishnava, Ramananda of Kashi, would be the teacher to provide it to him.

But since Kabir came from a humble community of Muslim weavers, he feared Ramananda wouldn’t accept him as a disciple. Thus, one day before the break of dawn, as Ramananda was on his way to bathe in the Ganges, Kabir went to the stairs that led to the river, and lay stretched across the steps, effectively blocking the way.

Tripping over Kabir in the darkness, Ramananda called out the mantra of his deity — “Rama, Rama!” — as is common for Vaishnava devotees in sudden and dangerous situations. Because formal acceptance of a disciple in Hinduism entails an official revealing of a mantra to said disciple, Kabir happily took the incident as his initiation, and a most meaningful step on his spiritual journey.

Being initiated into a Vaishnava Bhakti tradition, however, didn’t mean he identified only as a Vaishnava. In addition to the aspect of complete surrender stressed in Vaishnava bhakti lineages, Kabir was also deeply impacted by non-dual Hindu philosophies, as well as Islamic monism. Furthermore, Kabir is also thought to have been influenced by Sikhism, as he is purported by some to have even met the founder of the religion, Guru Nanak.

Actually, it could be said Kabir’s poetry was a pluralistic expression of all the religious traditions prevalent during that period, especially in tow with the stream of devotional poetry inundating much of India between the 14th and 16th centuries. Including poet-saints such as Namdev in Maharashtra (14th century), Narsinh Mehta (15th century) in Gujarat, and Mirabai in Rajasthan (16th century), all were part of a movement that vehemently strove to break down the barriers of religion, making it more open and available to the common man, regardless of a person’s gender or social status.

Kabir, specifically, was alive during a time when such openness was sorely lacking. His home city of Varanasi was a place of great diversity, with people from different religious traditions and social backgrounds. But the ability for people to pursue their religious practices was hampered by turbulent political unrest.

For centuries, Muslim invaders had been waging war, taking over kingdoms in the subcontinent, and forcing their religion on the people, generally by threat of the sword. Because of this, many Hindus who converted, did so only in name, never actually giving up the beliefs of their prior faith.

The period leading up to the downfall of the Delhi Sultanate in 1526, as Islamic rule began losing its grip on the subcontinent, was thus marked by rising tensions between the Muslims and Hindus, leading to frequent confrontations, as well as the destruction of sacred sites.

Observing a level of inequality and abuse of power during his era, Kabir acted as a social critic, speaking out against the hypocrisies he felt were being displayed by people of both faiths.

Oftentimes his rhetoric made him into a more direct target for the oppressive powers that were, including that of Sikander Lodi, ruler of the Delhi Sultanate.

As one story goes, a group, consisting of various Hindu and Muslim leaders, along with Kabir’s own mother, approached Lodi to complain about Kabir’s so-called incendiary philosophy and influence.

When the sultan summoned Kabir for questioning, the poet declared his faith in Ram. Outraged by the bold announcement, Lodi ordered that he be thrown to the Ganges in chains. As Kabir was tossed into the water, however, the chains broke, allowing him to safely float to the surface.

Determined to see the saint dead, Lodi then tried to have him killed in a fire, but the flames mysteriously burned cool. Finally, the sultan attempted to have him trampled to death by a wild elephant, but the animal wouldn’t rush at Kabir, however much it was prodded to do so.

Amazed by what he saw, Lodi concluded Kabir was virtuous and innocent, and proceeded to try to shower him with riches, but the saint refused the sultan’s wealth, electing to simply return home.

Whether this event actually took place, it seems not all of the religious heads in Varanasi became convinced of Kabir’s virtuosity, as they eventually succeeded in having him banned from the city.

Thus, at roughly 60 years old, Kabir left his home, and is said to have traveled throughout Northern India with his followers as a “poet of love,” before moving to Maghar (a Muslim weavers’ town near the Nepalese border), where he ultimately passed away.

Legend has it that when Kabir died, his Hindu and Muslim followers argued over how to conduct his final rites, with the Hindus wanting to cremate the body, and the Muslims wanting to bury it.

Agreeing, at the very least, to cover the body in flowers, both groups became stunned when after doing so, the body mystically disappeared, leaving only the flowers. In the end, the Muslims kept one half of the blossoms to be buried in Maghar, and the Hindus took the other half to be buried in Varanasi.

Today, there is a samadhi (shrine) dedicated to Kabir in Varanasi, as well as one in Maghar, both of which draw thousands of pilgrims every year, all of who go to pay their respects to the poet-saint who fearlessly spoke out in pursuit of the ultimate truth.

His life and work continue to be kept alive and vibrant by Kabir Panthis, a religious group dedicated to the teachings of Kabir. Consisting of various sects and subsects, they all revere The Bijak, an anthology of Kabir’s verses, as their primary scripture

As a way of bringing this piece to a close, here is just a sample of that scripture — potent words of Kabir’s that powerfully convey the tonality of his spiritual disposition:

The worlding ponders:

domestic life or yoga?

He loses his chances

while others grow conscious.

Doubt breaks up the whole world,

no one can break up doubt

He alone will break doubt

who can make out

the word.

It’s the kind of speech

no eye can see.

Kabir says, listen

to the word spoken

in every body.

Grasp the root: something happens.

Don’t be lost

in confusion

Mind-ocean, mind-born waves —

don’t let the tide

sweep you away.

To learn more about Kabir, his work, and his life, read “The Mystic Mind and Music of Kabir” here.