For those who have not paid close attention, the historical impact of Hindu influence in America probably seems somewhat minimal, limited perhaps only to the various health benefits of yoga and meditation.

A true dissection of America’s history reveals a much different reality, however, one in which the threads of Hindu influence are so vast and embedded so deeply, that the fabric of American thought and culture as we know it today could not have otherwise been woven.

The first of these threads was sewn during the early years of our nation’s existence, when John Adams, both a founding father and the second president of the United States, desired to pursue a serious study of religion. Though the topic had always been of great interest to him — as a teenager he had even considered becoming a minister — his responsibilities during America’s formative years had left him with little time.

Once his presidency was over, however, he had the opportunity to indulge this passion. Like many who were educated during the period of the Enlightenment, Adams had Unitarian leanings, and therefore placed more of an emphasis on the role of reason in his religious explorations, even if that caused friction with the existing doctrines of Protestantism.

Thus, when in 1812, his friend Thomas Jefferson recommended to him the writings of Joseph Priestley, a Unitarian minister who had published works that compared Christianity to other religions — Hinduism in particular — Adam’s interest was piqued.

Going through Priestley’s writings, Adams became riveted by Hindu thought, as he launched into a five-year exploration of Eastern philosophy. As his knowledge of Hinduism and ancient Indian civilization grew, so did his respect for it. In one letter to Jefferson he wrote:

“Where is to be found theology more orthodox, or phylosophy more profound, than in the introduction to the Shasta?”

And in another:

“We find that materialists and immaterialists existed in India and that they accused each other of atheism, before Berkly or Priestley, or Dupuis, or Plato, or Pythagoras were born. Indeed, Neuton himself, appears to have discovered nothing that was not known to the ancient Indians. He has only furnished more ample demonstrations of the doctrine they taught.”

Though Adams never actually published any of his ruminations on Hinduism, the Unitarian community, and his role as one of its more progressive thinkers, was pivotal in nourishing the soil from which emerged a more consequential legacy of Hindu studies by prominent American thinkers.

This legacy took shape in the 1830s as Transcendentalism, a philosophical, social, and literary movement that emphasized the spiritual goodness inherent in all people despite the corruption imposed on an individual by society and its institutions. Espousing that divinity pervades all of nature and humanity, Transcendentalists believed divine experience existed in the everyday, and held progressive views on women’s rights, abolition, and education.

At the heart of this movement were three of America’s most influential authors: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau.

Emerson’s impact on American thought and culture, in particular, can’t be overstated. Not only have his works been translated into more than a dozen languages worldwide, he is the most quoted American in the 20th-century press.

A powerful force in broadening America’s outlook on religious tolerance, alternative thinking, and moral living, his writings are infused with Hindu concepts and principles. His reverence and respect for Eastern philosophy was nothing short of profound, as he once said about the Bhagavad Gita:

“It was the first of books; it was as if an empire spoke to us, nothing small or unworthy, but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence which in another age and climate had pondered and thus disposed of the same questions which exercise us.”

With a knack for taking ancient Indian philosophy and expressing it in a way digestible for modern culture, Emerson was Transcendentalism’s intellectual ring leader, whereas Whitman and Thoreau stood out for really putting Eastern concepts into practice.

Whitman’s own Hindu influence shines through in much of his poetry, eventually culminating in his magnum opus, Leaves of Grass, a collection of loosely-connected poems that convey, in celebration, his outlook on philosophy, humanity, and the individual’s role within nature.

Fueled not only by the “ancient Hindu poetry” he said to have read, but also by a spontaneous and transformative mystical illumination he experienced around the age of 30, Whitman became seen by many as almost a sort of poetic conduit of spiritual expression.

Thoreau’s Hindu explorations also transcended beyond that of intellectual ruminations. Especially identifying with the lifestyle of India’s yogis, Thoreau remained an ascetic throughout most of his own life. Famously building a cabin in the woods to fully experience nature’s spiritual essence, he wrote:

“One may discover the root of the Hindu religion in one’s own private history, when, in the silent intervals of the day or the night, he does sometimes inflict on himself like austerities with a stern satisfaction.”

Despite Emerson’s frustrations that Thoreau, in fact, spent too much time being the “captain of a huckleberry party” instead of embracing a larger literary role in the Transcendentalists mission to reform America’s rigid psyche, Thoreau’s impact was still immense.

Indeed, even half a century after his death, it was Thoreau’s essay, Civil Disobedience, that found its way into a South African jail cell and into the hands of a persecuted Mahatma Gandhi. Leaving a deep impression, the work became a potent spark of inspiration for the development of Gandhi’s satyagraha brand of nonviolent resistance in the effort to gain India’s independence.

Gandhi and the satyagraha movement, in turn, profoundly inspired and affected many of America’s most prominent Black leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., and subsequently, America’s nonviolent civil rights movement.

But before the 1960s counterculture that facilitated such a movement could come into full bloom, the fields of America’s inspiration would still need ploughing. Fortunately, the clandestine mission of the Transcendentalists prepared America for a more direct injection of Hindu thought and practice.

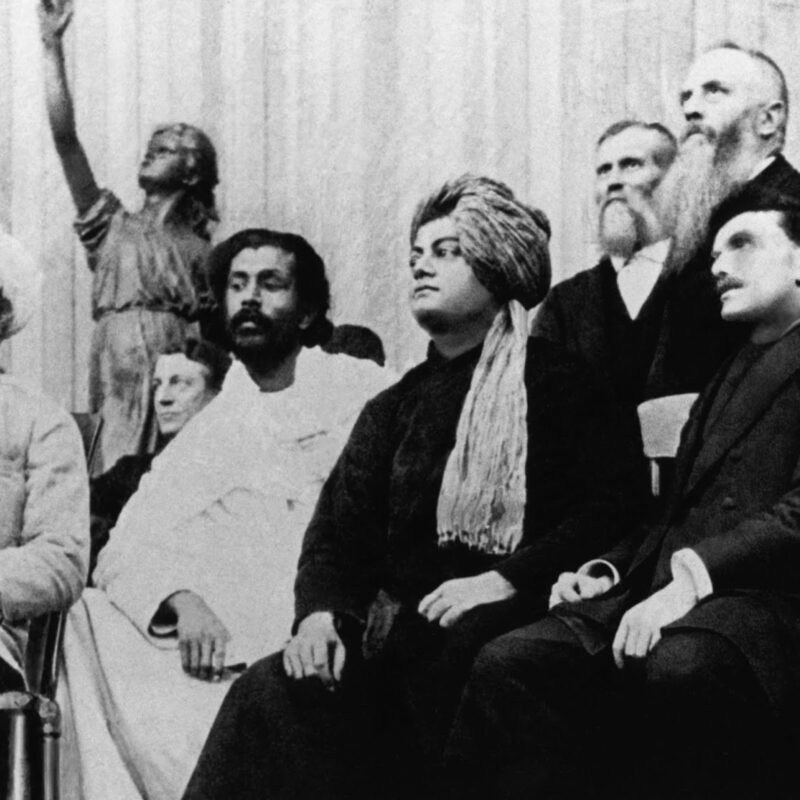

This injection took place in Chicago, when Swami Vivekananda gave the opening speech at the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions, in which he officially introduced Hinduism to America, calling for an end to fanaticism, and a focus on religious tolerance.

Describing Hinduism as “a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance,” Vivekananda emphasized the value of all religions on the path of spirituality, citing the Bhagavad Gita:

“Whosoever comes to Me, through whatsoever form, I reach him; all men are struggling through paths which in the end lead to Me.”

Decrying the Christian notion of original sin, he spoke of the divine nature inherent in every individual, instigating a shift in America’s spiritual understanding of man, the Divine, and their relationship.

Highlighting diversity, inclusivity, and unity, Vivekananda’s blend of spirituality with logic and reason made him the star of the show, opening the door of Hinduism to many whose view of it had been previously distorted by a Protestant lens.

As he went on to tour the US, publish voluminous writings, open the first Vedanta Society in New York, and train disciples to carry on his work, his profound influence manifested as a sort of foundation from which so much of America’s future culture was built.

The bones of this cultural building were put into place by America’s next generation of prominent intellectuals, like Aldous Huxley, Christopher Isherwood, Huston Smith, Joseph Campbell, and J.D. Salinger — all of whom received mentoring from Vedanta Society swamis.

The full form of this building, however, really began to take shape when Huxley’s generation of intellectuals turned into the baby boomers, who were exposed to an influx of Indian Hindus and swamis who began pouring into the US from the 1960s onwards. As Eastern philosophy thus made its mark on cultural icons like the Beatles and African American leaders like MLK, many of the ’60s movements in connection to civil rights, women’s rights, gay rights, and the environment, became infused by an undercurrent of Hindu-inspired thinking.

This undercurrent has flowed into the 21st century — providing renewed inspiration as the issues of the ‘60s still exist today in some form or another — and it will continue to flow into the next 50 years.

For from the time John Adams set this current in motion, it has gained an unstoppable momentum, one that has always pushed our country forward in love, compassion, and open-mindedness.

To learn more about Hinduism’s contributions to America, including its rich traditions of yoga and meditation, visit Hindu American Foundation’s blog page here.