Today, nearly all of Afghanistan’s 38 million people are Muslim and Islam is the official religion of the country. This, however, has not always been the case.

Before becoming an Islamic state, Afghanistan — being the subject of numerous conquests over the centuries — was once home to a medley of religious practices, most of which prospered for long periods. Of all these religions, none is older than Hinduism, whose connection to the region goes beyond that of modern historical dating.

Once upon a time, much of Afghanistan was part of an ancient kingdom known as Gandhara, which also covered parts of northern Pakistan, spreading over the Peshawar Valley, Kabul River Valley, and the Pothohar Plateau. Today, many of Afghanistan’s province names, though slightly altered, are clearly Sanskrit in origin, hinting at the region’s ancient past. To cite a few examples, Balkh comes from the Sanskrit Bhalika, Nangarhar from Nagarahara, and Kabul from Kubha.

Though Gandhara’s earliest mention can be found in the Vedas (Hinduism’s most ancient sacred texts), it is better known for its connections to the Hindu epics the Mahabharata and Ramayana. Most famously, Gandhara is described as the kingdom from which the queen Gandhari came, whose son Duryodhana fought and lost a great war to his cousins, the Pandavas.

Gandhara is also renowned for being home to Taxila (located today in Pakistan near Rawalpindi), a city described in the Ramayana as being founded by Rama’s younger brother Bharata, who named it after his son Taksha. (Some say it was Taksha who founded Taxila). Furthermore, Taxila is said to have been where the Mahabharata was first recited.

Situated at the junction of three great trade routes connecting Eastern India, Western Asia, and Kashmir (a renowned Hindu center of learning) and Central Asia, Taxila was and remained wealthy and prosperous for a long time, even as it changed hands from one ruling empire to the next.

Home to one of the world’s earliest universities that gained recognition as a center of not only Hindu and Buddhist learning, but also the arts and sciences, Taxila attracted students from all over, producing many of history’s finest minds. Some of these include:

- Charaka: an Ayurvedic physician who compiled the Charaka Samhita, a foundational text on Indian traditional medicine;

- Jivaka: also an Ayurvedic physician, who specialized in marma (a therapy involving the stimulation of sensitive points on the body), panchakarma (a vigorous detoxification process that rejuvenates the body), and surgery, and who became famous for treating Gautama Buddha;

- Panini: a Sanskrit grammarian who compiled the Astadhyayi, a work on Sanskrit grammar that is now considered one of the greatest intellectual achievements of any ancient civilization;

- Chandragupta Maurya: the founder of the Mauryan Empire, which covered much of the Indian subcontinent from 321 BCE to 185 BCE;

- Chanakya: prime minister of the Mauryan Empire and mentor to Chandragupta Maurya, he also authored the Arthashastra, a classic Indian treatise on statecraft;

- Vasubandhu: one of history’s most prominent and influential Buddhist philosophers.

Gandhara eventually came under Mauryan rule in the fourth century BCE. During this time, Ashoka, Chandragupta’s grandson, embraced Buddhism. As a result, the religion grew and flourished, even after the region was taken over by the Greeks and other subsequent rulers.

The mid-third century CE to 543 CE, however, saw the emergence of the Gupta empire. Staunch followers of Hinduism — especially Vaishnavism — the Guptas strove to revive Hinduism, which had been in decline due to the popularity of Buddhism.

But in the fifth century CE, the Gupta empire came to an end as the Huns invaded, causing widespread devastation and destruction. Taxila, among the destroyed, never truly recovered.

For a while, local leaders fought amongst themselves for power in the area until it was taken over by the Turkish Shahi dynasty of Kabul, which controlled the area until the ninth century CE, when they were replaced by the Hindu Shahis.

Holding sway over the Kabul Valley, Gandhara, and Western Punjab, the Hindu Shahis were the last great Hindu rulers of Afghanistan and built numerous temples and religious monuments throughout the region.

Unfortunately, the Hindu Shahi dynasty was ended in the 11th century with the eastward expansion of Muslim forces from Ghazni. Buddhism was more or less eradicated that same century, as other religions were also either stamped out or made to dwindle during the Muslim conquests of Afghanistan.

Despite this, Hinduism managed to survive alongside Sikhism, which became established in Afghanistan about 500 years ago when the founder of the religion, Guru Nanak, is believed to have visited the region. Because the people of both religions have similarities, get along with each other, and share places of worship, they have an undeniable kinship, and are even often viewed as a single community in Afghanistan.

For generations most of them have lived in the city of Kabul, and could be found at the Asamai Mountain — a place that has always been a hub of worship for Hindus and Sikhs, and notably home to the famous Asamai Hindu Temple, named after the Hindu goddess of hope.

Sadly, increased persecution has caused this community to decline at an accelerated speed in recent decades.

In the 1970s, there were about 700,000 Hindus and Sikhs in Afghanistan. In the 1980s, this number fell to about 200,000-300,000 when the Pakistan-backed Mujahideen, supported by the US Central Intelligence Agency, won the Soviet-Afghan war and took control of the country.

The Afghan Mujahideen, who came into power with Pakistan and US help, then formed the Taliban in the early 1990s, commencing a period of time that proved particularly dark for Hindus and Sikhs. Forced to wear yellow armbands for identification, Hindus and Sikhs became the victims of constant and widespread atrocities that included kidnappings, murders, and the stealing of properties.

The Taliban’s attitude towards minority religions became so aggressive that they commenced a campaign to rid Afghanistan of all idolatry, destroying statues and deities — even of religions that had already been eliminated. One of the more infamous examples of this was when, in 2001, they demolished the Buddhas of Bamiyan, two sixth-century statues of Gautama Buddha carved into a cliff in the Bamiyan Valley. A seventh-century painting of Shiva Avalokiteshvara that was inside the caves of Bamiyan was destroyed with them.

As of 2021, there are fewer than 700 Hindus and Sikhs left in Afghanistan, according to The Associated Press.

And with the US set to completely pull out of Afghanistan by August 31, 2021, and the Taliban at its greatest strength since 2001, it seems inevitable that there will soon be no Hindus and Sikhs left in the region.

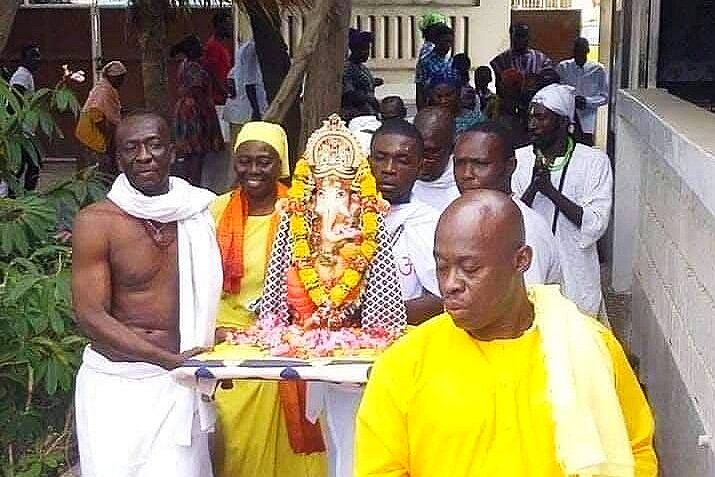

Fortunately, Afghanistan’s Hindu community continues to exist outside of the country. Many Asamai temples named after the famous one in Kabul have been established around the world, including Amsterdam, London, New York, Frankfurt, and Faridabad.

After centuries of persecution, the communities of these temples are a reminder of Afghanistan’s once rich and prosperous Hindu history.

An enduring people who have been the subject of terrible atrocities, their continued perseverance to practice a religion in spite of all odds is a testament to the depth and richness of their culture and devotion.

It is through such perseverance that perhaps this culture can prosper once again.

For anyone wanting to visit an Afghan Hindu temple in the US or learn more about the community, visit asamai.com and/or asamaihindutemple.com.